How-To Guide: Deciphering an Ancient Greek Manuscript

Examples, diagrams, and high-def photos that break down the evidence of Ancient Greece through the Iliad's Venetus A

In March of 2023, I published an article called “The tale of a 3,000-year old text” in which I discussed the oldest manuscript in the world which contains a complete text of Homer’s The Iliad: the Venetus A from the 10th century AD. I linked the manuscript’s journey through the centres of world power with The Iliad’s indefatigable influence on the histories of the world; from the philosopher Aristotle to the Italian Renaissance to the French Revolution. I described a short history of the creation of the manuscript itself, and how close examination of its pages yields three millennia of secrets, from the very utterance of ‘Homer’ in the mists of time down through the centuries of turmoil to the technology of the present day.

If you haven’t read that previous article, I highly suggest you read it before continuing on here to have a better grasp of what the Venetus A is and what I will describe next. Understanding the plot or characters of The Iliad is not necessary, and indeed the epic poem will be little-discussed in favour of the commentary which surrounds the Iliadic text, which is known as “scholia”.

While the last article discusses the 1000-year lifetime of the Venetus A and its impacts on perception of history, in this article I move away from the vague high-level description in favour of delving into the actual pages of the manuscript. In particular, I aim here to create something of an entry-level guide to the scholia of the manuscript. It is these scholia, or commentaries, on the text of The Iliad which provide information not just about the story, but of the debates of ancient philosophers like Aristotle and Plato, of the ancient writing technology used by the original librarians of Alexandria, of cultural practices like funerary rites in ancient Greece, and of how ancient Greek was actually pronounced.

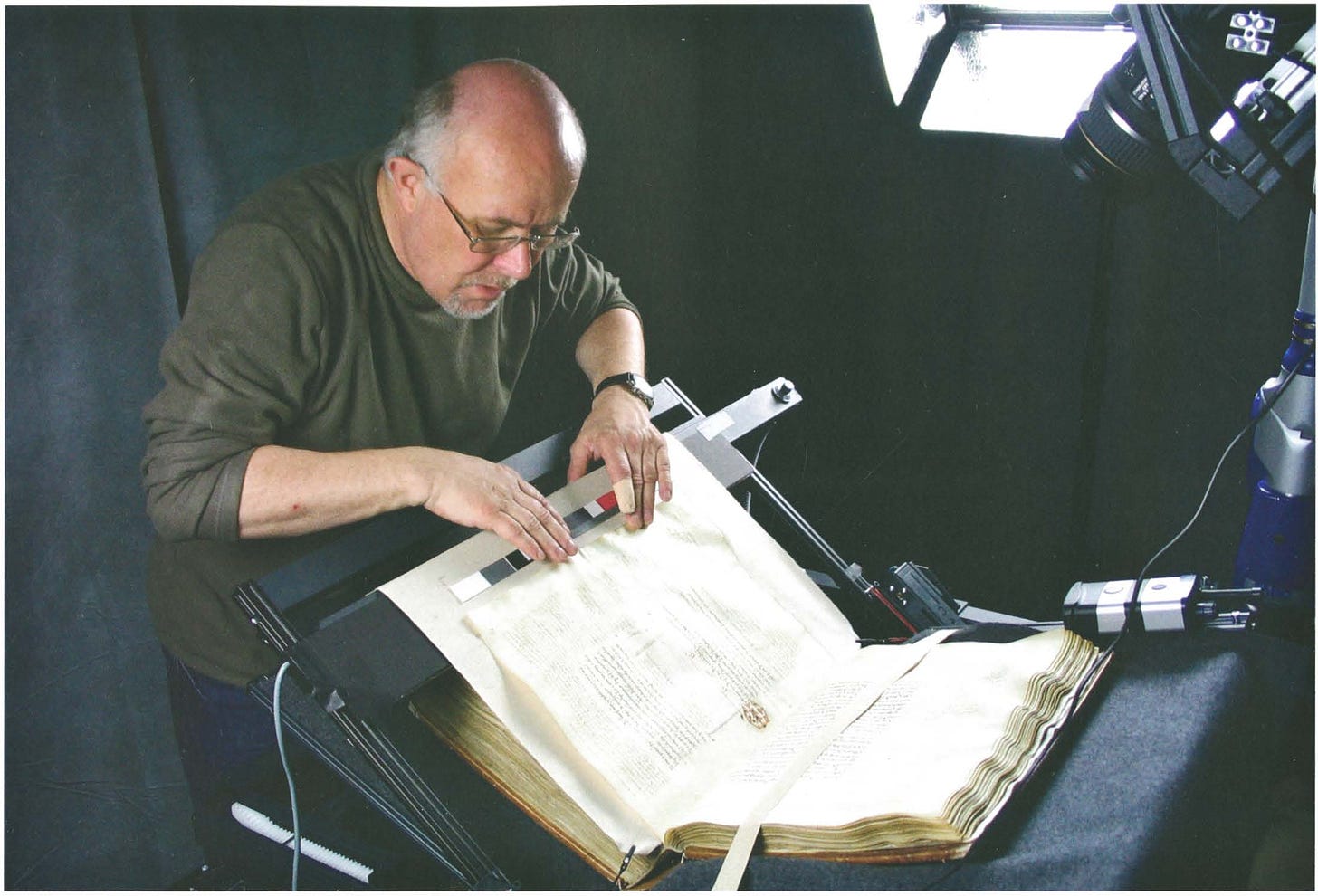

But forget words. Thanks to the digitization efforts of the Homer Multitext Project and many other books and resources (as I outline in my annotated bibliography), I present to you here images of four different pages from the manuscript, presented with different levels of details and mark ups to highlight relevant information. I also created a timeline of the transmission of The Iliad and an intellectual lineage tree of the individuals I discuss in order to help keep details straight and provide context. In the second half of the article, I delve into four specific verses and scholia from the manuscript to illuminate specific examples of how a page on the Venetus A functions, how scholia work, and what information they provide.

My goal in this newsletter is to answer the question: just how do we actually know what the ancient Greeks said? If you’re canny, you’ll have noticed that I said the Venetus A is from the 10th century AD, well over a thousand years after what most people think of as ancient Greece. Yet when going to Greece or reading about any ancient Greek topic, phrases like “Herodotus the first historian said that…” and “300 Spartan warriors fought at…” abound with such frequency I have become tempted to wonder what kind of documentary filming technology existed in the ancient world.

I recognize it is not possible to provide the nuance of history at every turn, but I became frustrated by the lack of accessible resources on this process of historical knowledge-discovery so I decided to work on this guide myself. No, there is no first-hand account of ancient Greece in literature. The words of the ancient Greeks were considered so incredibly valuable that the painstaking work of copying and re-copying texts by hand continued across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa through all the eras of history; despite war, despite plague, despite famine, and despite cultural and technological change. The vast majority of ancient Greek texts were lost, but the fact that any survived at all is remarkable. Most are fragments, quotations, and paraphrases -- but survive they have. It is in the scholia where we can see this ancient craft of textual dedication.

Format of Venetus A

Let’s start with the first page of The Iliad. In the Venetus A, that is Folio 12R. A ‘folio’ is a page, and 12 means it is the twelfth folio/page in the book. The ‘R’ stands for Recto, which means it’s the front of the page, while ‘V’ would stand for Verso, which is the back of the page. When the manuscript is open in front of you, 12R would be on the right side of the book, and 11V on the left side.

As you can see, the page is busy and contains text in different formats and placements all across the page. There are some differences between each page of the Venetus A, but the scribe who copied the text carefully planned each page to fit usually 25 lines (or verses) of the text of The Iliad (the ‘Iliadic text’) and all the scholia associated with those 25 verses. The reader of the manuscript can thus have the book open and see the related scholia on the same page of the Iliadic text it comments on without needing to flip around.

The scribe of the Venetus A ruled each page of the manuscript with a series of horizontal and vertical lines to keep his text straight and organized into various spatial categories. The ruling of Folio 12R can be seen in Figure 3. Although the lines are almost invisible to the naked eye on some pages, by using high fidelity images from the Homer Multitext team and an analysis by scholar Myriam Hecquet I was able to superimpose the ruling onto an image of Folio 12R. I also eliminated the natural colour on the page so I could better highlight different categories of text on the page.

Light blue highlights the first 25 verses of the over 15,000-verse poem of The Iliad. This text takes pride of place being centrally located on the page between two pairs of vertical lines. The horizontal lining here is much higher than the other horizontal lines, which allows the writing to be larger for this Iliadic text. Of course, the largest writing is the illustrated ‘M’ in the left-margin of the page. ‘M’ is the first letter of the first word of the epic, Μῆνιν, ‘Rage’. I’ll say more on the first lines of the epic in the Examples section of this article.

The title of the epic, ΙΛΙΑΔΟC, ‘The Iliad’, is written just above the Iliadic text. Next to it is the book name/number, ΑΛΦΑ, ‘Alpha’. The Iliad is organized into 24 books, one for each letter of the Greek alphabet. The top of the page is reserved for a one-line summary of the events of Book 1/Alpha. The Iliad isn’t written in blank verse, but with a certain prosody and rhythm, and the summary of the book follows this same pattern. Each book of the Iliad has such a summary and title.

Dominating the page and surrounding the Iliadic text are the primary scholia (highlighted in red). They are for the most part lined, although the height is lower compared to the Iliadic text. The amount of text contained in the primary scholia alone far outweighs all of the rest of the text in the manuscript combined, and there are many other manuscripts with scholia that are not found in the Venetus A.

The yellow colour signifies ‘secondary scholia’. There are different technical terms for the scholia, but for simplicity I have sorted them into just two types: primary and secondary. The secondary scholia is visually marginal compared to the primary scholia, being placed in margins without any lining in different sections of the page (which is why this type of scholia’s technical terms usually involve the word ‘marginal’). There are several differences between primary and secondary scholia which I will expand on in the examples section.

Finally, there are the critical signs, highlighted in green. There are just a handful of them on Folio 12R, and they are all immediately to the left of the Iliadic text, placed within the pair of vertical lines which contains the Iliadic text. These are extremely important, and quite unique in their form to the Venetus A. They connect the Iliadic text to some of the scholia and help a reader interpret meaning of the text and the historical origin of some scholia.

You may notice some other text and markings like page numbers and stamps on Folio 12R. These were added in the centuries following the creation of the Venetus A. Of these, an interlinear gloss between the lines of the Iliadic text was designed to aid the reading of the text is considered scholia, but I will not discuss it here. You may also wonder why the first page of The Iliad is on Folio 12R, and not Folio 1. This is because the first 11 folios of the Venetus A do not contain any Iliadic text or scholia and are much worse preserved, disordered, and have been copied over or added to over time. They are fascinating but are also beyond the bounds of this discussion.

The Venetus A is considered a complete text of The Iliad. However, when Cardinal Bessarion (who donated the manuscript to the Marciana Library in Venice where it is still held) came into possession of the manuscript in the 15th century, he found 19 pages were missing out of 654. He added these pages back in himself based on other manuscripts of The Iliad, although unfortunately the scholia for those pages was lost.

Authors and History of Scholia

The high level of organization of the Venetus A, which contains very few mistakes, is one method by which scholars believe the scribe was likely copying the Venetus A based off of one, two, or perhaps three similar manuscripts that are now lost. Those lost manuscripts may have contained the exact same material as what is found in the Venetus A (if he was working off of one manuscript) or the same material but split across different texts which the scribe compiled into this one deluxe edition.

The number of different texts and authors that are contained in the Venetus A far exceeds just a handful, so how did all those texts come to be found in a single manuscript? And why is there so much scholia anyway? What do they talk about?

Ever since the composition of Homer and his epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey, they have been foundational for Greek culture. In a sense, they are sacred, religious texts. But they are also much more. Especially The Iliad, which as a fountainhead of culture isn’t necessarily a holy text above reproach. Since the 6th century BC Homer’s works have been attacked as immoral, illogical, impossible, or contradictory. Debates between Homer’s supporters and detractors went on for hundreds of years. As a keystone text, The Iliad is also compared to other texts and referenced in countless ways regarding religion, literature, language, laws, warfare, family, fate, emotion, philosophy, and history. Fragments of comments on the content of The Iliad and all other manner of ancient Greek life live on in the scholia of manuscripts like the Venetus A. One of these debaters is the philosopher Aristotle, whose text is preserved and quoted through a later philosopher Porphyry, both of whom I discuss in the scholion of Example #4.

Perhaps even more of the scholia in the Venetus A are, however, related simply to the difficulty of transmitting such a vast corpus through the millennia. When the scribe of the Venetus A first put ink to parchment in the 10th century AD, The Iliad could have already been 2,000 years old – yet it’s the oldest complete version of The Iliad we have. Even the most ancient tiny fragments of The Iliad are from centuries and centuries after the original composition of The Iliad. There is remarkable uniformity between all the versions of The Iliad, but nevertheless there must be discrepancies: verses in different places, differing spellings of words, different sections included or excluded.

One of the tasks the first librarians of ancient Alexandria of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC devoted themselves to was sifting through all the different manuscripts they had of The Iliad. Their goal was to compare their differences and their authenticity and to create a single standard of The Iliad based on the original text of Homer. I discuss two of these early librarians, Zenodotus and Aristarchus, in the scholia of examples #1 and #2.

The problem with this approach is that there likely never was a single version of The Iliad. Research over the past centuries has pointed to The Iliad as originally composed and passed down orally by a more-than-one number of initial composers in the centuries before the 8th century BC. It’s possible Homer was a single individual who collected these stories and made a ‘standard’ original written version of the epic (like the Brothers Grimm), and perhaps this occurred in the 8th century BC too, but evidence is inconclusive.

As the centuries wore on, the preservation of the Homeric texts was entirely in textual form. It’s oral origins utterly forgotten. Homer and The Iliad remained towering figures, but surrounding them now were centuries of scholars, librarians, philosophers, and other commentaries. Those too became integral to the study of Homer and Greek culture writ large. Later scholars studied the works of the librarians before them and created their own texts about The Iliad, about ancient scholarship, and about the precise ways ancient Greek should be written and pronounced. I discuss the work of two of these scholars, Aristonicus and Herodian, through whom the librarians’ work is preserved, in the scholia of examples #1, #2, and #3.

The history told over the past few paragraphs can be seen in the upper half of the timeline in Figure 5. But what occurred from 300AD until the creation of the Venetus A in around 950AD is difficult to show in the timeline because text wasn’t created in this period which would be added to the Venetus A. Instead, during a long period of economic, cultural, and technological shift, what occurred for the texts of the ancient Greeks was a period of preservation, editing, compilation, and great loss. As the libraries and urban centres which fostered the creation of the ancient Greek texts disappeared, most textual production shifted to monasteries. Strapped for cash, only a small number of texts could be preserved. Instead of copying entire books individually in their papyrus scrolls, several different books or fragments of whatever books were existing were all compiled together into single editions of a book like the Venetus A.

The Venetus A specifically cites the source of much of its scholia. At the end of nearly every book in The Iliad, there is a citation which says that:

“Placed in the margins are the signs of Aristonicus and the work of Didymus entitled “On the Aristarchean edition,” and some material also from the “Iliadic prosody” of Herodian and from the work of Nicanor entitled “On punctuation.”

The four scholars mentioned in these citations have been named the Viermännerkommentar (in German), which is shortened to VMK and means “Four-Man Commentary”. It’s believed that a text which compiled the works of these four together was created in the 5th and 6th centuries. I will discuss the work of two of them, Aristonicus and Herodian. However, these four do not cover the full range of scholia in the Venetus A, there are many other scholia discovered to have come from the works of different individuals.

To sum up all of these stages briefly:

The text in the Venetus A (10th century AD) was written by an unknown scribe based off of one or more manuscripts.

Those earlier manuscripts (ca. 3rd-9th centuries AD) contained The Iliad and all the scholia seen in the Venetus A. Those manuscripts have since been lost.

Those lost manuscripts were themselves compiled and edited in the preceding centuries based off of other manuscripts (1st-3rd centuries AD) which contained the texts of scholars known today as the VMK (e.g. Aristonicus, Herodian) and others (e.g. Porphyry).

The works of those scholars were based on copies of earlier works from the 4th to 2nd centuries BC (e.g. Librarians of Alexandria Zenodotus and Aristarchus; philosopher Aristotle).

The works of those ancient librarians and philosophers were based on oral and written discussions (7th to 4th centuries BC) about the attributes and provenance of the work of Homer.

Homer may be a singular genius who compiled and first wrote down a vast corpus of oral texts (in the 8th century BC) co-created by an entire bronze-age ancient Greek culture (from well before the 8th century BC), which is known as The Iliad.

This incredibly complicated process took place over thousands of years and is a major source of how today we have the text of The Iliad, a wealth of knowledge on the writing and pronunciation of ancient Greek, awareness of scholarly technology in ancient libraries and schools, philosophical musings of great figures like Aristotle and Plato, and various cultural, historical, mythological, archaeological, linguistic, and religious information.

Four Examples of Scholia

I will now describe four different examples of scholia in the Venetus A. I selected these four to provide a range of authors of the scholia, which are represented on the page in different locations and with different fonts, different intellectual lineages, and which touch on technical as well as historical and cultural topics. These four examples are by no means exhaustive, comprehensive, nor necessarily applicable to all other manuscripts. I hope for them to give a taste of how scholia function on a page and the type of information contained in scholia.

Examples #1-3 (see Figure 7) are all on the same page of the manuscript -- the first page of The Iliad on Folio 12R. The examples in the scholia move forwards chronologically in their historical provenance (from Zenodotus in the 3rd century BC to Herodian in the 2nd century AD) and thus follow the intellectual lineage outlined in Figure 9.

Here’s a brief snapshot of what’s happening at the very start of The Iliad. The Greeks, led by the commander Agamemnon and the heroic warrior Achilles, are in their 10th and final year of war against the Trojans, who are led by Hector, in order to rescue the Greek princess Helen -- the most beautiful woman in the world. The epic starts with the famous word, Μῆνιν (Rage), and continues: “Rage – sing, muses, sing of the rage of Achilles, murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans [i.e. Greeks] countless losses”. The god Apollo has just unleashed a plague as divine punishment upon the Greeks for taking one of his priest’s daughters as war prizes.

I wanted to also include an example which involves Aristotle and provides us with interesting cultural and historical information through a scholion. Aristotle isn’t quoted on the first page of The Iliad, so Example #4 (see Figure 14, below) is therefore from Folio 290R which comes towards the end of the book and fittingly closes out the story, which I will describe below.

To help keep track of the intellectual lineage of these specific scholars in these specific examples, please refer to Figure 9.

Example #1

The first example scholion is relatively simple. A word in the eighth verse of The Iliad is written σφωε (which means roughly the pronoun “they”). If you follow this verse to its terminus on the right, there is a scholion which is written in smaller text which faintly says “Zenodotus wrote σφῶϊν [instead of σφωε as seen in the Iliadic text]”. The word is similar but clearly not exactly the same.

Hundreds and hundreds of years after the composition of Homer’s epics, Alexander the Great from northern Greece conquered most of the known world 336-323BC. Throughout his campaign he is said to have always kept a copy of The Iliad under his pillow, esteeming it as a treasury of military virtue. He conquered the ancient land of Egypt, and set up a brand new capital at the mouth of the Nile, Alexandria. The Greek dominance of the eastern Mediterranean had begun, and the Library of Alexandria was one of its treasured institutions. Its first librarian was appointed in 285 BC, a scholar known as Zenodotus (325-270BC).

Zenodotus at the library of Alexandria began the process of attempting to standardize many of the ancient Greek texts, including The Iliad. With the memory of the oral composition over centuries of Homer’s works, Zenodotus and scholars after him made a huge effort to compare and contrast a huge range of extant manuscripts at the time in order to produce the one, true, original version of Homer’s genius. However, some modern scholars consider that this was ultimately an impossible task, as the likely-oral composition of The Iliad meant there never was a single version of the text.

Back to the scholion: The scholion from this example which mentions Zenodotus wasn’t an original analysis or edit by the scribe of the Venetus A. The information about what Zenodotus’ own edition of The Iliad said comes from the work of a later scholar Aristonicus, who lived 250 to 300 years after Zenodotus during the time when Jesus had just begun spreading his teachings. More on Aristonicus in Example #2.

What this scholion shows is that the transmission of The Iliad was already quite varied in Zenodotus’ time, and over the centuries there continued to be disagreement and confusion over the precise way the text ‘should’ appear, whether due to different, competing editions of The Iliad or simply from errors or illegible text creating typos in the process of transmission.

One last note before moving on: The script (the type of lettering or font) of the verse from the Iliadic text and the script of the scholion in this example are different. In the detail of Figure 10 you can see the Iliadic text on the left and the scholion on the right. Even without being able to read any Greek, there is a clear difference between the rounder, connected, cursive writing of the Iliadic text (i.e. miniscule script) and the blocky, individual, ‘upper-case’ letters of the scholion (of whose script has the technical name of semi-uncial, although I will just call it majuscule script for simplicity).

I wrote before how the creation of the miniscule script in the 9th century AD was one innovation which helped save and preserve ancient Greek texts. The Venetus A was written in the 10th century AD and is thus part of this process of transferring texts to minuscule script. The miniscule script was likely created as a much more efficient way of writing when compared to the older majuscule script. The script seen in the scholion here is ‘majuscule’, and this lettering is preserved for several reasons which I will discuss in Examples #2 and #3.

Example #2

The second example shows us more about two technical features which aid in the reading of the complicated manuscript page and which reveal layers of historical depth. The first feature (critical signs) help alert the reader to the existence of scholia and the second (lemmata) help the reader to locate the scholia.

Just to the left of the fifth verse of the Iliadic text is a small notation, which is known as a critical sign. A critical sign serves to alert the reader of The Iliad that there is a comment related to that particular verse (in this case, verse 1.5). The critical sign is essentially like the small superscript numbers we use in today’s texts which point to footnotes or endnotes elsewhere in the text that discuss something valent about the particular line in the main body of the text.

Why is this useful? Before the advent of the form of the book itself, The Iliad would have been written on its own set of papyrus scrolls, without the range of comments and notes surrounding it as seen in the Venetus A. For example, as noted in Example #1 the first librarian of Alexandria, Zenodotus, in the 3rd century BC collated a range of existing texts of The Iliad seeking to create one standard edition of The Iliad which would ostensibly be the true, original version. In the next century, the sixth librarian of Alexandria, Aristarchus (216-145BC), might read from Zenodotus’ text of The Iliad on one set of scrolls, while he continues the process of seeking to create the original text of The Iliad by placing his own comments and disagreements with Zenodotus in a separate scroll. Aristarchus would place the same critical sign next to both the original verse on Zenodotus’ text of the Iliad and his own editorial comment in each of their respective scrolls to help a future reader (or himself!) identify and keep track of which comment is concerned with which verse in The Iliad.

There are several types of critical signs with different meanings. The critical sign next to verse 1.5 in the Venetus A means that Aristarchus placed the critical sign there to note that he disagreed with Zenodotus’ rendition of the text of verses 1.5 and 1.6. Aristarchus would then write his justification for a different line against Zenodotus on a different scroll.

There is another layer to add here. In the Venetus A, the scholia are not copies of the early Alexandrian librarians’ work, like Zenodotus or Aristarchus, but of later scholars. Most of the scholia about Aristarchus (including this one) are from a later scholar named Aristonicus, who lived 150 years after Aristarchus and sometime between around 50BC and 50AD. By this time, the library at Alexandria had fallen into decline and Aristonicus moved to Rome to write his book On the critical signs of the Iliad and Odyssey (this is the book noted in the VMK citation in Figure 6). A quotation from this work has filtered its way down through time to the Venetus. As in Example #1 -- where Zenodotus’ word selection was noted in a scholion but not included in the main Iliadic text -- the Iliadic text of verses 1.5 and 1.6 of the Venetus A presumably agrees with Aristarchus’ version, but Zenodotus’ version (through both Aristarchus and Aristonicus) is still noted for posterity and for the process of scholarship.

Having said all this about critical signs, there is no critical sign next to the scholion in this example, only the Iliadic verse. During the transition from works being on different scrolls to everything contained in a single book, most of the critical signs next to the scholia were left out. So how would a reader know where to find the scholion which is commenting on the particular verse? Here is where the second technical feature of Example #2 comes in: the lemma.

In the Venetus A, the scholion of Example #2 is like most of the primary scholia – and unlike most of the secondary scholia as in Example #1 – in that it begins with a “lemma” (plural: lemmata). A lemma is essentially a short quote excerpted from the main Iliadic verse. The reader could therefore read verse 1.5, see the critical sign which alerts them to a comment about that verse, and then find the lemma in the scholia sections of the page by looking for words from verse 1.5. This process may be clearer in the translated Verses 1.5 and 1.6 below.

Verse 1.5: every bird; thus the plan of Zeus came to fulfillment,

Verse 1.6: from the time when first they parted in strife

Scholion: CAME TO FULFILLMENT FROM THE TIME WHEN FIRST – Aristarchus concluded that… [rest of scholion continues]

In this example the lemma is capitalized, while the scholion is lower-case, to emulate how in the original Greek most lemma are in a form of majuscule while the primary scholion are in miniscule script. In fact, lemmata can contain unique information because unlike the verses in the Iliadic text and the rest of the primary scholia, the lemmata are written in majuscule script, as opposed to miniscule script. Many of the other scholia, like the marginal scholia mentioned in Example #1, also use the majuscule script.

Why did the scribe of the Venetus A write some of the manuscript in the miniscule script and others, like the lemmata, in majuscule script? What information does the usage of these two scripts provide the reader as well as modern historians? The short answer is that it’s complicated and scholars today aren’t always sure nor agree.

The proper answer, unsurprisingly, would require us to plumb just too far into history for this article. Suffice it to say that all of the different texts that are in the Venetus A, from Homer’s Iliad to Aristonicus’ work On Critical Signs, were all distinct texts that were edited, copied, excerpted from, and lost to varying degrees until they were brought together between the same two covers in the Venetus A. There are different combinations of these and other texts in other medieval manuscripts, but the way that the scribe of the Venetus A presented some texts in the newer minuscule script (e.g. the Iliadic text and primary scholia) while others are still preserved in their older majuscule script (e.g. the secondary scholia and the lemmata) allowed for visual demarcation between the various sources of texts in the manuscripts. For instance, the majuscule script generally preserves older and more fragmented scholarly material, such as from Zenodotus, while the miniscule script preserves the newer and more complete texts and commentary. Finally, the majuscule and miniscule scripts preserve and present information in different ways, which I will elaborate on in Example #3.

This example therefore shows how to move through a page of the manuscript and make sense of it (especially if one can read Greek). A reader would read from the main Iliadic verse to a critical sign that points to somewhere on a page to a lemma with built-in information on the provenance of the comment and finally to the comment about the line itself.

Example #3

The third example is similar in form to the first example. Except here, instead of the scholion highlighting disagreement over the spelling or meaning of a particular word, this scholion provides information on how specifically the ancient Greeks pronounced their words.

The eighth verse of the Iliadic text is the word “ξυνἕηκε” (which can be read as the verb “bring together”). Next to the beginning of the line is a small, faint scholion written in the majuscule script which says “Δασύνεται το ξυνἕηκε”. I won’t get into linguistics here, but the comment is saying that the word “ξυνἕηκε” should be ‘aspirated’ (pronounced) in a particular way.

This comment comes from Herodian, who wrote a book called “Iliadic Prosody” in the 2nd century AD. In this book and others, Herodian seeks to reconstruct the poetic meter, the accentuation, and generally the grammar and pronunciation of words and phrases of The Iliad. Did Herodian believe that The Iliad was initially a text of oral tradition and trying to rescue that pronunciation? Not necessarily. As a slightly less ancient person than the other scholars I have discussed thus far, Herodian was grappling with the ways that spoken Greek had radically transformed.

The Greek spoken and normally written in the 2nd century AD is called “Koine Greek”, and is the language of the Greek New Testament. The first librarian of Alexandria, Zenodotus, was already 400 years before Herodian. 400 years of language difference? That’s like when you struggled through a semester of reading Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night and then your teacher said, “oh, but Shakespeare is still Modern English, wait until we read Chaucer, now that’s Middle English….”. Through the Alexandrian librarians, Herodian was trying to reconstruct pronunciation of “Homeric Greek” without necessarily knowing about its oral origins, but recognizing still the importance of oral recitation in that ancient world in an unfathomable age before himself.

In general, the 2nd century AD saw a revival of interest in the language of both classical (5th century BC) and pre-classical Greek writers who spoke an already ancient language to people like Herodian. Since the spoken and non-literary Greek language had evolved considerably, their reconstruction of earlier Greek would have been through series of highly technical texts, copied and excerpted through time. That same complicated process of transmission of Greek texts is how recent scholars rely on certain words, phrases, scholia, and other texts to learn to read Greek and understand how it’s spoken. The use of the majuscule script in particular, which is written with different word spacing, letters, and other markings, preserves elements of even more ancient spoken Greek than the later miniscule script.

Example #4

Example #4 comes from the third to last book (22 out of 24) of The Iliad, just after Achilles of the Greeks has slain the leader of the Trojans, Hector. Immediately after killing Hector, Achilles pierces holes in Hector’s ankles, ties his body to his chariot, and drags his bloodied body face-down around the Trojan city towards the Greek camp. This is done in full view of Hector’s mourning family. Worse still, Achilles continues for days to try and mutilate Hector’s body in this way. One reason for Achilles’ rage is that Hector killed Achilles’ close companion Patroclus, and so (in Book 24 now) Achilles takes to dragging Hector’s corpse around Patroclus’ grave in the Greek camp.

If you’re repulsed by this act, know that even by ancient standards, this act of gloating and desecration was seen as an abomination, an act of an uncivilized and ignoble beast. The response to Achilles is severe, which is truly saying something in a work as violent as this, and even the otherwise irresponsible and childlike gods, including Zeus, step in to stop Achilles.

On the bright side, you’ve just learned that you have something in common with Zeus!

You also share an opinion with many ancient thinkers, who as early as the 6th century BC attacked Homer’s works on moral grounds. How could Homer write and celebrate such horrific acts, they asked? Homer also had his defenders. These debates, not just on the immorality of Homer as in this example, but also on the illogicalities, impossibilities, or contradictions within his work, went on for hundreds of years by the time Aristotle came into the picture in the 4th century BC.

Aristotle, the famous philosopher and teacher of Alexander the Great, composed a text called Homeric Problems in which he provided solutions to the various problems cited in debates on Homer’s works. This book is largely lost, except for fragments of his argument like those in the scholia of manuscripts on Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. The Venetus A, on Folio 290R, has a scholion attached to verse 22.398 which provides evidence of one of Aristotle’s solutions. Namely, a rationale for why Homer describes immoral behavior in The Iliad, specifically the desecration of the body of a slain opponent in war.

Aristotle defends Homer by essentially appealing to a form of historical and cultural relativity. The scholion reads that one can’t criticize Homer for simply reporting on the traditional practices that went on in ancient times. He writes that although it may be reprehensible to drag a dead corpse around another man’s grave, the perpetrator Achilles, who is from a region called Thessaly, is following a Thessalian custom that is in fact still (as of Aristotle’s time) practiced in Thessaly. Therefore, Homer can’t be criticized for writing about it, and perhaps Aristotle was arguing the practice itself can’t be criticized for its traditional or ancient provenance.

In this example, we see how scholia can preserve otherwise lost analyses of philosophers like Aristotle, and in so doing also preserve fascinating cultural, historical, and even genealogical information. Personally, I find the appeal to cultural relativity eerily modern.

Once again, the text of Aristotle doesn’t come directly to the Venetus A (even through copies of copies ad infinitum), but as excerpts and fragments through a much later scholar named Porphyry. Porphyry was a scholar who lived some 600 years after Aristotle in the 3rd century AD, and wrote his own book called “Homeric Questions”. Porphyry likely had copies of Aristotle’s own works to draw on for this book before they were lost, in addition to others who wrote on the topic of Homer. Again, there are only fragments of Porphyry’s Homeric Questions, but in fragments such as those preserved in the Venetus A, it quotes and draws on information from ancients like Aristotle that were used in ‘parlor games’ of the intellectual elite who did their own battle by showing off various trivia and historical knowledge. In this way we can come to understand how not only those in Porphyry’s 3rd century AD spoke about and understood ancient poetry, but even some preservation of Aristotle’s words in the 4th century BC.

Where to go next?

If you ever travel around the Mediterranean basin — either in-person or through books and media — and hear of historical speeches and quotes, I encourage you to be curious about how it is possible that we can even begin to know what somebody said thousands of years ago. I hope this article and the examples I provided have shed light on a complicated, little-spoken about process which is the source of a massive amount of European civilization’s history and cultural knowledge.

If you would like to see my sources for this research or would like to take a look at a manuscript or ancient author of your own interest, please see my article below which serves as a guide to doing this kind of research as an amateur and as my annotated bibliography.

If you have any questions or feedback on this article, please reach out in the comments below.

For sources on this research, please check out my post below. I continually update it with my sources as I work on these articles. If you are looking for a specific reference, please comment and I will do my best to help you.

Thanks for taking the time and effort to try to explain something I've often wondered about myself. I thought your explanation of how the texts were organized, main text, surrounding texts and text in the margins was just as interesting, along with the examples. On a side note, I can only imagine the sore eyes trying to read the tiny margin writing! Overall, a really great effort and clear explanation. Thanks.

L. Tsiktsiris.