An Unbroken Text from the Hands of Antiquity

Edfu's guidebook to Greek Pharaohs and temple history

My aim for Culture Cross is to answer the question “How do we know what the ancient Greeks said?”. While exploring the transmission of ancient Greeks texts from antiquity to today, perhaps what is most surprising is that Greek literature doesn’t exist since antiquity per se: it survives in the form of much later, altered copies of the original works. Originally written on relatively fragile papyrus, Greek texts that don’t get copied face the very real fate of being lost forever. Architectural ruins, too, often fade away.

Texts that are so exemplary and useful that they continue to be copied, such as those by the philosopher and priest Plutarch, sometimes endure as not only the remaining evidence of the original words of the author, but as surviving architectural witnesses of long lost ruins, too. Over the millennia, as ‘Greece’ became ‘Classic’ and then ‘Ancient’, the reputation of the Greek civilization in modern societies skyrocketed based on the attestation of the relatively few ancient Greek texts that were preserved. Why shouldn’t the marble creations of the fabled Greeks be just as provoking as their words?

This assumption has resulted in disappointment. Ruins don’t always live up to the fantastic prose of the ancient authors or the imaginations of their eager modern audiences. This was the case during the excavation of Delphi and its famous Temple of Apollo, where archaeologists literally held copies of ancient literary sources -- like Plutarch -- right in their hands, but ended up let down with what they found (and perhaps more importantly, what they didn’t find).

“The tantalizing words on the page didn’t often align with what was on the ground [at Delphi]. By the end of the ten-year dig there was a feeling that the ancient sources had lied to them [the archaeologists and classicists]. Some extraordinarily fine pieces of sculpture, scattered inscriptions, and architectural shards had been uncovered, but compared to all the wonderful objects and allusions in the ancient literature, it simply didn’t measure up.” – Michael Scott, author of Delphi: A History of the Center of the Ancient World

A Text Preserved in Sand and Stone

There is another side to this fascinating coin. Let me describe the Temple of Horus in Edfu.

Just like Delphi’s Temple of Apollo, this is another temple that was abandoned after the 5th century AD, lay hidden underneath centuries of debris, and began to be excavated in the 1800s. The difference at Edfu is that the archaeologists discovered arguably the best preserved ancient temple in the world. They also went in without existing texts about this temple. Not an original, not a copy. Instead, they discovered it in situ.

Let’s venture across the Mediterranean to Egypt, up the Nile River, past the Great Pyramids, past the Valley of the Kings, past Luxor. Let me describe to you the Temple of Horus in Edfu. Although we are in Egypt, this is a place worth exploring for the topic of ancient Greek textual transmission.

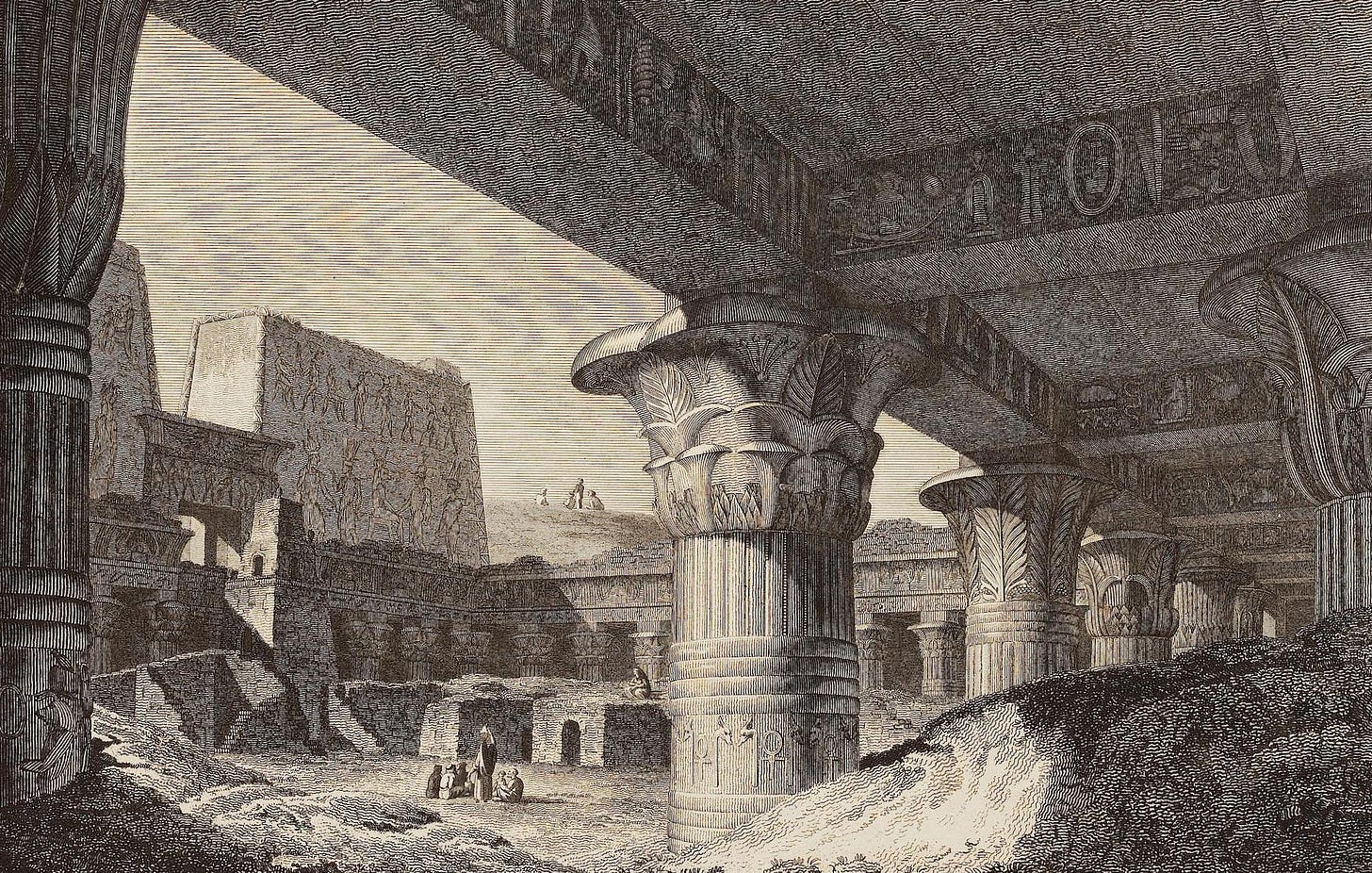

“This is my third visit to Edfu, and with each visit its temple seems to increase in grandeur… What I have been able to see of the reliefs is perfect to a high degree and reveals a particular feeling for beauty.” – V. Denon, Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte

A Hieroglyphic Guide

I visited the temple at Edfu just weeks after my visit to Delphi, and unlike the rather spartan (no pun intended) ruins of the temple in Delphi — which was essentially a perimeter of foundation stones — the temple in Edfu struck me. The past presented itself to me immediately as I walked between the monumental entrance gates into the marvelously preserved temple. It was complete with intact roofs, chambers divided by full walls, corridors snaking between them, and staircases leading to grand halls with gigantic columns blooming towards a ceiling with its original stars — painted thousands of years ago — still twinkling down at me like the night sky.

Even more amazing than the architectural preservation of the structure are the reliefs on the temple walls which include artistic depictions of historic and mythic events and, to my delight, a treasure trove of texts. Inscribed right onto nearly every square inch of walls, columns, and passageways are ancient texts describing ancient recipes for ointments, how the temple was measured out, the material of the tools used for carvings, how the god Horus avenged his father’s murder, and much more. A hundred years ago, Egyptologist Emile Chassinat arduously documented the temple’s inscriptions: in total they amount to 3000 pages across eight published volumes, not including any of the additional volumes of his photographs.

As I explored the temple, deciphering the purposes of the rooms, I followed a guidebook. This guidebook is totally unlike any other I have experienced. At Delphi’s Temple of Apollo, for example, one of the main sources of information about the temple’s function and operation comes from Plutarch, who was once a priest of the temple, but who is so far removed from the creation of the temple and its centuries of peak fame that many of his texts’ discussions are exactly trying to answer the riddles of how the temple came to be, about its mysterious meanings, and about how it has declined. But none of Plutarch’s actual writing materials survive: we read a copy of a copy of a copy of Plutarch’s works, edited and transcribed into a medieval manuscript produced far from Delphi. A guidebook for Delphi would then pepper in some of these ancient-via-medieval text excerpts alongside a healthy dose of scholarly interpretation. A visitor still ends up having to conjure up images of the temple themselves while looking at the pile of scattered stones called a temple ruin.

What if, instead, the visitor had a priest of the temple lead them through the temple himself?

The Edfu guidebook, based on one particular text found carved into a wall at Edfu, is like this. It features an ancient priest’s text about the history, construction, measurement, materials, and mythology of the temple. The priest who wrote the text (whose name is lost) lived during the construction of the temple and incredibly, the original creation of the text, supervised by this priest, survives. In fact, until it was copied by modern archaeologists, it was the only version of the text in existence.

As the excavators uncovered the Temple of Horus in Edfu, they didn’t do so with thousands of years of textual tradition in their hands. They dug deeper and deeper, discovering an exceedingly well-preserved structure with information about the creation, function, and layout of the temple literally etched right into its walls. There is no story of disconnect between textual history and architectural remains at Edfu, they are not only both wonderfully preserved, but the fate of its literature and its structure have been intrinsically tied together since their creation.

Edfu’s Guided Text

The location of the priest’s text, which is written in Egyptian hieroglyphs like all of the temple’s original texts, stretches for 300 metres as it encircles the temple along a girdle of its enclosure wall.

It describes the dates of the construction of the temple, political events during its development such as rebellion and war, what kind of food and drink were had to celebrate its opening, how the God of the temple inhabited the temple, and annual processions and rites. After that, the text describes the size of every room and corridor in the temple, artworks and texts in those rooms, and other details right down to the material of the doors and their bolts.

Here are a few examples of historical, architectural, and specific measurement information the enclosure wall text provides, as translated by the lead of the Edfu Project, Dieter Kurth.

Historical Event

This beautiful day in the 10th regnal year, day 7 of the month Epiphi, in the time of the Majesty of the Son of Ra Ptolemy III Euergetes I, was the day of the Senut-festival, when the measurements of the temple were laid out on the ground.

This excerpt describes how the Pharoah performed the first measurement for the layout of the temple in 237BC.

Building Materials

Work was resumed in the House of the Strong One (Edfu) in year 30 of this king [Ptolemy VI]: the tracing out of the inscriptions with ink and the carving of bronze tools, the embellishing of its walls with gold, the laying on of the colors, the completion of its wooden door leaves, the mounting of its pivots with perfect bronze, the carving of the holes for its bolts with bronze tools, the gilding of the doors, thus completing the Temple of Edfu in superb workmanship executed by the best craftsmen by year 28, month 4 of the season of Shemu, day 18 of His Majesty, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt The Heir of Epiphanes, Son of Ra Ptolemy VIII, blessed, Euergetes II and his consort, the Ruler and Mistress of the Two Lands, Cleopatra II. The whole work took 95 years, from extending the measuring rope to the Entering the Temple Festival.

This excerpt describes some of the decorative touches added to the temple before its completion. The 95 years mentioned here refers not to the entire temple complex but the central part of the temple, which was completed on September 10, 142BC. The enclosure wall and its text was completed after this date.

Room Measurements

The Great Seat in the midst of the chapels and surrounded by the corridor, which is 3 and five-sixths cubits, measures 19 and five-sixths cubits by 10 and one-third cubits. The doors are to its right and left, and give access to the surrounding chapels. The processional bark of the God Horus, his magnificent shrine next to it, and his great Naos of black stone that is next to both of them, they are wonderful to behold.

This is an excerpt of a long part of the text which describes the purpose, positioning, and precise measurement of the rooms and corridors throughout the temple. Here the text is describing the very centre of the temple, where the God Horus would reside for most of the year. This is unlike my discussion in my article about Delphi’s temple, where there is very little material either textually or archaeologically to determine where exactly the oracle provided her prophecies within the temple.

Is Edfu’s text relevant for Greek literature’s transmission?

Why is a comparison between a temple in Greece and a temple in Egypt relevant to the topic of Greek textual transmission? After all, Edfu’s Temple of Horus is a seat of an Egyptian deity, has Egyptian iconography, and texts describing Egyptian history, religion, and mythology in Egyptian language and hieroglyphs.

But after exploring the great tombs and necropolises of Ramses and Tutankhamun from over 1000 years before Edfu’s Temple of Horus, and even more ancient still, the Great Pyramids, Edfu seemed almost young. Although its textual and artistic inscriptions are aesthetically similar to those of earlier eras, it was markedly different in other ways. It’s not so simple to describe the temple as “Egyptian”; for one, the overall plan of the temple clearly takes on Greek influence. This is because the pharaohs who are honoured throughout the temple walls (Ptolemy III through Ptolemy X), despite appearing here as indigenous Egyptians, are from a family which originated in Macedonia, in northern Greece.

After Alexander the Great died in 323BC, his close friend and military officer Ptolemy I brought his body to Egypt – whose people had initially welcomed the Macedonian Greeks as liberators – to bury the fallen conqueror and consolidate Ptolemy I’s own control over Egypt. Later, the Temple of Horus was built between 237-57BC, a period in which Egypt was ruled by the Ptolemaic Dynasty — the final dynasty of ancient Egypt.

I make no claim that the Edfu texts are ancient Greek literature in the way Homer’s or Sophocles’ or Plutarch’s are. They are clearly a different genre. The Edfu texts descend from the incredibly ancient Egyptian tradition and the Egyptian priest, trained in that tradition, led the creation of the texts primarily for an Egyptian audience. But the Greek Pharoahs, who worked to appear not as foreigners but to insert themselves into the indigenous modes of governance and culture, were now part of that audience. Indeed, as Pharoah King-Gods, the Ptolemies are themselves characters and words in the story. As they heavily patronized Egyptian religion through the support of numerous cults across Egypt, a vibrant Greco-Egyptian syncretism took root. The Egyptian cult of Isis, for example, became widespread across the Roman Empire, including in conquered Greece, where Plutarch would write about the Egyptian goddess Isis in the same stroke as the Temple of Apollo in the 2nd century AD.

As Greek and Egyptian culture transformed and conjoined each other across the Mediterranean, under the Ptolemies Egypt became a centre of Hellenistic culture. The newly created city of Alexandria almost immediately blossomed into one of the wealthiest cities in the world, allowing it to fund and stock its famous Library. The library, which was really a scholarly hub and university, opened just prior to the beginning of the construction of the Edfu Temple.

Throughout the 180-year construction of Edfu’s Temple, nearly all of the Greek texts that survive today were collected from across the Mediterranean and brought to Alexandria to be edited, standardized, and published there. When modern scholars try to ascertain what someone said in 5th century BC Athens, they’re doing their best to restore those words to what an Alexandrian edition suggests they said, since that’s usually as close as we can get. Alexandrian scholarship indelibly moulded Greek texts, and anyone exploring the everlasting mark left by Greek culture in the twenty-three centuries since the library’s creation has — knowingly or not — ventured there through the implicit materials in their textual study.

This is the cultural and scholarly environment within which the texts of the Temple of Edfu were inscribed, funded and patronized by an ethnically Greek Pharoah and Greek ruling class who all supported the Egyptian priestly class. The original Greek-language scrolls and codices from the Library of Alexandria are lost now, with only copies of those works surviving as later medieval manuscripts. Yet for millennia the original Edfu texts have endured.

What’s in a (Royal) Name?

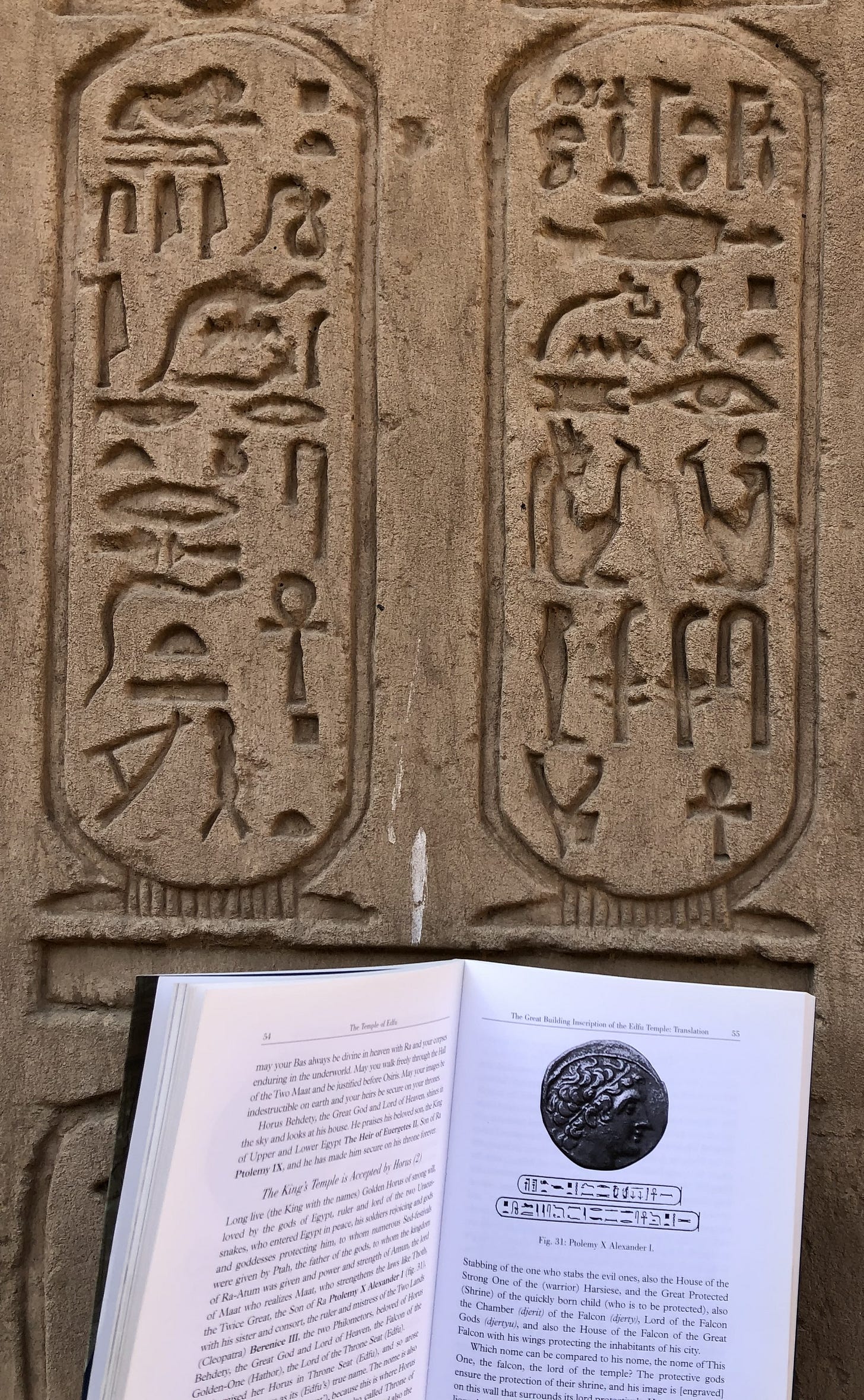

Incredibly, Edfu allowed me the experience of seeing an original source of literature — not a copy — right in front of me. I could read my modern translation of a text about a wondrous Egyptian temple, its varied history, and its Greek-named Ptolemaic Pharoahs, and then see the original source with my own eyes.

This isn’t a simple factor of materiality. Even in stone, there are no complete Greek literary sources. The closest would be a summary of Epicurus’ philosophy which was carved onto a wall in the city of Oenoanda, but less than a third of the text has been recovered. The text carved was also from over 400 years after Epicurus’ lifetime. Even then, this is a rare amount of surviving Greek text from antiquity.

Greek-language texts simply haven’t survive in the same way many Egyptian-language texts have. For example, a Greek historian named Polybius lived in the same century as the Edfu priest and also wrote historical texts that referred to individual Ptolemaic Pharoahs. I can see the original way the Edfu priest wrote the word ‘Ptolemy’ in Egyptian around 100BC, but I can’t see Polybius’ stroke of ‘Ptolemy’ in Greek. The closest I can get to Polybius’ writing is to see the name ‘Ptolemy’ written by a scribe named Ephraim who copied Polybius’ text over 1,000 years after the historian’s death.

The inverse is also true. The predilection for societies to copy Greek texts is what kept its ideals alive and flourishing. On the other hand, many Egyptian texts like those at Edfu’s Temple of Horus were not copied and thus would be lost forever, were it not for the incredibly dry climate of Egypt preserving the original text under sands.

For a period of time, the ancient Greek and Egyptian cultures came together and flourished before once again unravelling and shooting off in different directions. Fortunately for us, historical transmission doesn’t care if we label something ‘Greek’ or ‘Egyptian’, we can nevertheless appreciate their ruined architecture and remaining literature.

The primary source for this article is The Temple of Edfu: A Guide by an Ancient Egyptian Priest by Dieter Kurth. If you are interested in further reading on the topic of ancient Greek textual transmission, please read my annotated bibliography.

Edfu is amazing - so much history set forth in one place!