What innovations preserved Ancient Greek texts?

From the origins of writing to the first compendiums. (Transmission Pt. 2)

This is the second part of a series of articles on the transmission of Greek knowledge from antiquity to modern times. I recommend you read at least the introduction to the first part before reading this one. In the first part I introduced the concept of Ancient Greece.

The ancient Greeks are lauded as the originators of many aspects of civilization across the world. Philosophy, medicine, drama, biology, democracy, and even the study of history itself are all said to have originated in ancient Greece. Greek forms of architecture, art, religion, and mythology permeate our cultures today. This information comes to us not always as a general statement, but is often accompanied with a particular person, such as Herodotus with history and Hippocrates for medicine (until recently many doctors still swore a Hippocratic Oath upon becoming doctors). We also have very particular details of some of their deeds, such as the original performance of Medea by Euripides – the most performed Greek play in the 20th century AD – earning third prize in the City Dionysia festival in 431BC.

But we are also inundated with episodes of historical destruction, from the burning of the Library of Alexandria to the invasion of “barbarians” that took down the Roman Empire to censorship of Galileo by the church. The disappearance of information, especially over such a vast period of time, does not have to be the product of nefarious or unfortunate activities but can result from simple decay, neglect, or ignorance. Let’s not forget how much information is created today, and how much is lost. Researchers have already discovered more than 100 scientific journals that were created in the last twenty years and have already been lost forever due to lack of comprehensive archives. So how did ancient Greek works survive despite the odds?

In this article, I will sketch out the general history of ancient Greek work from their inception as oral works as far back as the 8th century BC through to the nadir of antiquity, when the cultures and institutions that utilized and maintained Greek work began to significantly decay. This will take us to about the 4th century AD. In the following two articles, I will continue this story through periods of Christian monasticism to the creation of the printing press in the 15th century AD. I will track these changes through noting a series of major technological and institutional developments. These innovations were sometimes an arena to cultivate further work, and sometimes they are the knot linking two last, desperate threads of information without which almost all of what we know about the ancient Greeks could have been lost.

Given the vast scope of this project covering thousands of years, it is heavily simplified here. It will still give you a grasp of the historical processes that led to the creation of many of our modern societies, and at the end of this series I will share a bibliography and highlight how you too can independently learn about fascinating cultural history like this.

Innovation 1 - Writing: The transition from oral to written culture

We wouldn’t know what an ancient Greek said thousands of years ago unless it was written down for us to read. But we do know what some non-Greeks said thousands of years ago, even though those words were only first written a thousand years ago. Sanskrit texts from the Rig Veda from around 1500-1000 BC in India were transmitted orally without being fully committed to text until sometime around 1000AD, and the oral tradition continues to survive among communities of Hindu priests using a highly complex form of mnemonic memorization to fix the texts’ precise sounds and guard against corruption. Scholars can assert with relatively high certainty that there has been little change to this Vedic literature over the ages.

We imagine writing things down makes it more permanent and secure, but writing can suffer from its own problems of corruption over time, particularly without a large healthy archive at hand to ensure consistency. In any case, work needs to be part of a broader shared culture of transmission to be maintained through either oral or written traditions.

The oldest Greek literature, The Iliad and The Odyssey, derive from one such oral tradition. Although these texts have been attributed to an author named Homer since antiquity, it is now most commonly asserted that Homer either wasn’t one individual, or at the very least that the huge epic texts penned under his name weren’t a work of individual genius but reflected the oral tradition of roving bards performing chapters from epics from town to town. The intuition that Homer’s works reflect hundreds of years old oral stories came from the fact that although he (whoever “he” was) seemed to live in the 8th century BC, the content of the epics and archaeological evidence suggest the time period of the works to better reflect 2nd millennium BC Bronze Age culture. Variations in the written evidence of the texts could be accounted for by bards’ own unique traditions based on location, individual style, or the broad time period of their performance, as well as interpolations and collations which were introduced the moment of writing them down.

When did the Greeks begin writing? Greece had writing systems in the 2nd millennium BC which were lost, and the subsequent few hundred years the Greeks appear to have gone on without a system of writing. An early version of the Greek writing system we know today began to develop as an adapted form from the Phoenician writing system in the 8th century BC. Phoenicia was a wide-ranging Mediterranean trading culture centered in the Levant which used its writing system for administrating trade across its lands; a purpose the Greeks too adopted for their writing. Greek writing was also used for some epigraphic inscriptions (to mark names on statues, for example), but these stone inscriptions were never used for major scholarly or literary texts as it was in some other places (like China’s Xiping Stone Classics of 2nd century AD which recorded seven Confucian texts in stone). In Greece, works of literature and philosophy remained on papyrus and parchment alone.

As Greece matured into the more recognizable city-states we know of today, like Athens and Corinth and Sparta, there was another important oral tradition in the culture of politics which focused more on competition. The city-states were, well, states surrounding a city. They were small enough that all citizens should theoretically be able to walk from the more rural portions of the state to the city, take part in its administrative functions, and return home in the same day. In a city like Athens, which had a democratic tradition that lasted some 170 years – with interruptions – from the 6th to 4th centuries BC, groups of men would meet in public places like town squares and debate all manner of things from politics to philosophy to setting out for war.

To explain and examine their arguments, they would quote on their earlier epics and texts, which weren’t mere cultural trivia, but which contained important information they could draw on and marshall in favour of their arguments, such as information about how the gods may act in a particular circumstance or on the methods by which their forebears cultivated their own societies. It was incredibly important to get these details and references right, and to be able to construct a well thought out argument to defend and advocate for your position. Effective speech could confer mastery over other people.

Enter the Sophists: a group of what are essentially professional teachers and speech coaches who sought to capitalize on this cultural practice by initiating a form of textual scholarship. They studied the words of the great bards and put them to paper, err, papyrus for later reference. They could claim to get the words of Homer absolutely right and sell services of rhetoric and grammar coaching, courtesy of their written words.

Not everyone liked this development, including the famous philosopher Socrates. In his view, men sequestered away scribbling texts in private missed the whole point of seeking the truth. The aim of debates wasn’t mere material knowledge, but to draw out the truth through the immaterial essence of the soul through logic and deduction with a face-to-face interlocutor in a method we have come to call the Socratic Dialogue. Removing the embodied person from the equation in exchange for letters on a page displaces truth and makes it mere ‘knowledge’, and potentially untrustworthy knowledge at that without the reputation of your interlocutor known.

It’s a little ironic to write a piece like this about the transmission of Greek classics, and then freely reference an episode of history from 2,500 years ago with an authoritative voice like this. The truth is that somebody without in-depth training in Ancient Greek (specifically the Attic dialect of 5th century BC Ancient Greek) and years of examining sources could not “know” this, and someone like me can only come to know this through translations and concise historical interpretations. Before I reach the conclusion of this series and you too may come to know the incredibly multi-layered and imperfect way in which this history is done – let me share one more interesting tidbit. When I mention the Sophists or Socrates ‘writing’, it was in fact not them writing. In Socrates’ case, it’s possible he never intended it to be written and it was his followers like Plato and his contemporaries who wrote them down. But in any case, the writer was often a well-educated slave to whom these works were apparently dictated.

Anyway, “write” the Ancient Greeks did, and even literature from the present began to be recorded, such as plays which were shared and re-performed. Many texts seemed to have been held at a type of public records office. Aristotle, a student of Plato’s Academy, continued to systematize and organize writing even more and seek out knowledge in the material world to write about it in countless books (along with his pupils and colleagues). Writing was quite firmly established in its niche, but it was disorganized and disparate. However, the strengths of writing were still latent, it was heritable and portable – and therefore – expandable.

Innovation 2 — Library: The Standardization and Categorization of Knowledge

In the late 4th century BC, the Greek world expanded dramatically with the conquering of Alexander the Great. No longer did you have just a small city-state, you had Greek empires. And Greeks were intermingling and ruling over vast, multi ethnic, non-Greek populations in the ‘Outer Greek’ states which I discussed in Part One. Alexandria became an exceptionally wealthy city in the most influential Greek kingdom of them all, Egypt, which was ruled by a royal family from Greece (Macedonia) called the Ptolemies.

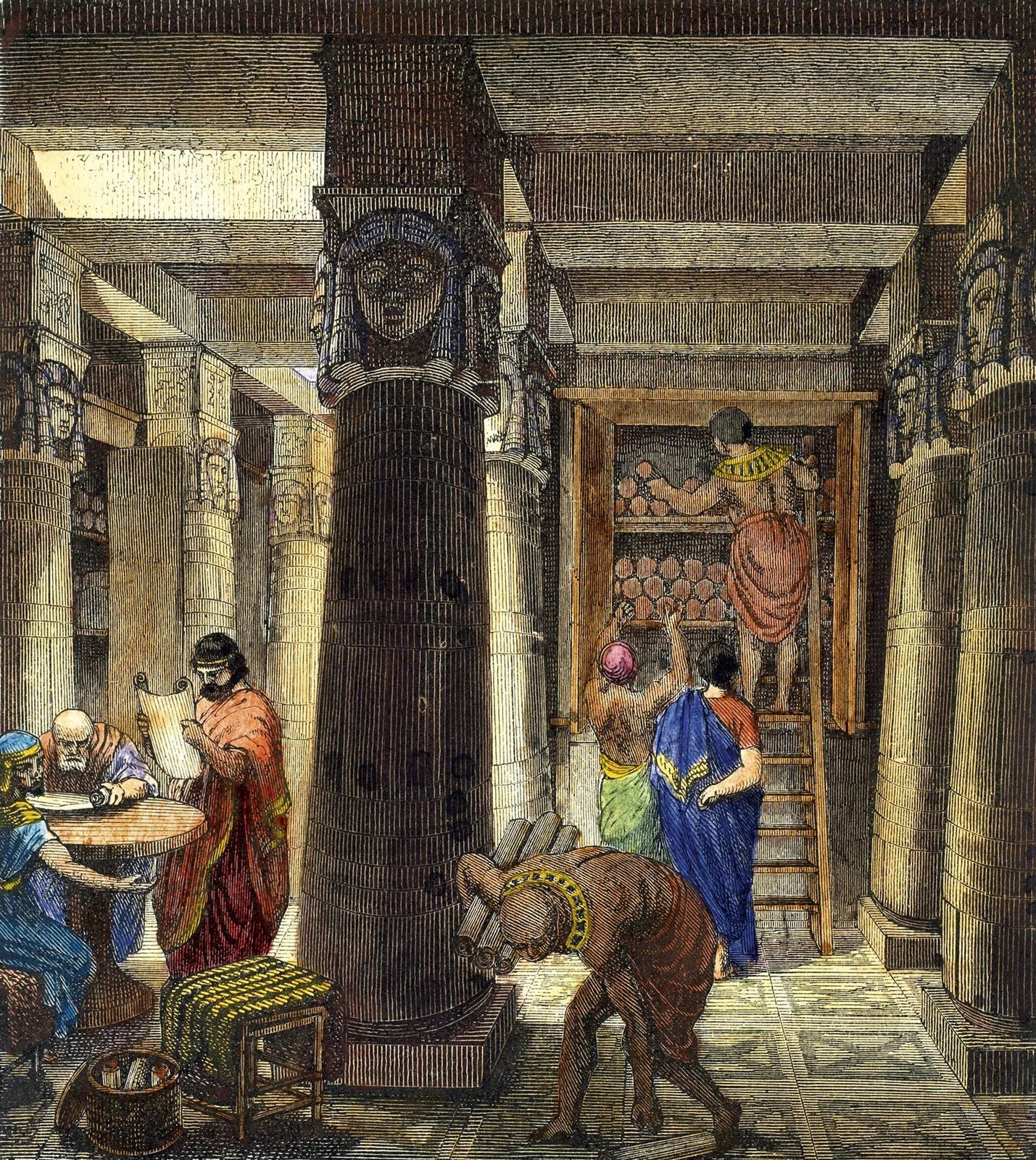

The needs of a kingdom like this was quite beyond what Greek society had already developed, and verbal debates in town squares just wouldn’t work for such an unwieldy empire. In the new empire, writing was fully realized for the first time as a superior form of knowledge creation and maintenance when compared with orality. The leading Ptolemies wanted to set out to collect the knowledge of the people’s and culture of their new empire, which expanded to a desire to collect all the knowledge of the world. The first two leaders of Ptolemaic Egypt initiated a Temple of the Muses, called the Mouseion (in modern times this would become the institution we know of as the museum). Scholars from across the Greek world were invited here with state supported money to do research, which was the first of its kind. They were also requested to bring whatever texts they could, and the Museum purchased as many other texts as they could from around the world, no matter the cost. These would be collected in the Library, which was a part of the broader Museum complex. No one knows just how many scrolls there were here, but estimates range from 40,000 to 500,000 scrolls at its peak.

But scrolls weren’t just collected for dusty shelves; they were organized, sorted, and systematized. The scrolls were compared and collated, criticized, edited, and copied again. The scholars wrote commentaries and analyzes of all manner of key fields of knowledge, and in the process created disciplines. These were sorted in the first library catalogue, or bibliography, the Pinakes, which also served as a quasi-encyclopedia that further connected information to each other. Through this compilation and separation, fresh knowledge could be brought to life by a scholar who never left the walls of the library. The portability and heritability of writing had reached one of its first apexes.

Were he still alive at the time, Socrates likely wouldn’t be happy with what he saw: the greatest poets burrowed in dusty stacks obsessed with academic pedantry rather than advancing the triumph of Greek verse. Another Greek poet in the 3rd century BC, Timon of Philius, famously derided the scholars of the Museum as:

bookish scribblers spending their whole lives pecking away in the birdcage of the Muses.

Yet the philosophers and scholars brought from across the Greek world didn’t work in isolation. They were provided all their creature comforts, as well as a scintillating intellectual environment among other scholars and the leaders of their society. The city-state was recreated in the smaller form of the museum, like a university, and they formed an elite class of society separate from much of the general population.

The contributions of the museums scholars cannot be overestimated today, and would likely have never been possible without the environment and vast knowledge on offer at the library. To name just a few: Euclid’s astoundingly influential geometry textbook Elements was put together here; Zenodotus collated and edited Homer’s works into roughly the forms we have them today; and Eratosthenes made a groundbreaking measurement of the circumference of the Earth.

The museum continued, even if its spark of genius of the 3rd century eventually faded. Even once the Romans conquered all the Greek controlled lands, they more or less continued to be a patron for libraries like Alexandria’s, and Galen’s work on medicine was completed in this period. More and more libraries were founded in Rome itself and across the Republic and then Empire; although Alexandria’s always remained the most important. Greek texts began to receive less attention over time as Latin finally began to assert its own literary tradition. Though in some fields like philosophy, Greek work was never rivalled until the Renaissance or another early modern period, although Latin did become particularly treasured in law and oration. In any case, by the end of the Roman Republic around 27BC, the institutions and processes that govern and guard the transmission of written records were in existence and were continually refined and consolidated which would transmit and preserve Greek and other texts for centuries to come.

However, through the whole period of antiquity, and even through the medieval period, there was a series of typographic problems that beset comprehension and introduced a high probability for error when copying. There was very little punctuation in writing and no word-division. Accentuation which helped as a guide for pronunciation and comprehension began to develop at the Library of Alexandria but wasn’t fully adopted until much later. Who exactly was speaking in a play wasn’t indicated clearly, and it could be difficult to ascertain if a text was lyric or verse. There were some major moments in which improvements were made, but in general it was slow and gradual, and many errors or inconsistencies in writing were actually from the earliest periods of writing rather than later mistakes in comprehension. Some of these issues could be addressed alongside the next innovation, the Book.

Innovation 3 — Book: The transfer of papyrus scrolls to parchment books

If it weren’t for the codex (the book) the amount of materials we would have from ancient Greece would be dramatically reduced. Between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD, as the Roman Empire began to lose control of its vast economy and empire, the first major bottleneck of transmission of ancient literature took place: the wholesale transference of literature from papyrus rolls to codices.

I haven’t yet discussed the material and form which writing was contained in during the periods up to this point. There are hardly any fragments from the earlier classical period, but some of the facts about the extant scrolls from the Hellenistic period (i.e. during the time of the Library of Alexandria) may hold true for the earlier periods as well. The writing implement was a type of reed pen with ink, and the surface was papyrus of which only one side could contain writing. The sheet was eight to ten inches high and could contain 25-45 lines. The papyrus would be contained in two rolls, in which a reader would unroll one side in order to read the text, re-rolling it on the other side as he goes on, and then rolling it all back to its original state when done to ‘reset’ the text. The maximum capacity of the text was relatively small, with multiple scrolls needed for any work of even moderate length. Some papyrus could be up to ten metres long, making this form exceedingly difficult for making reference to specific text, and as such orality was always an important part of the tradition of knowledge creation with such technology.

A form of the book as a multi-sided wax tablet had been used for educational purposes, letters, and casual purposes for hundreds of years, but the idea to expand this form with more pages and to use it for serious literature wasn’t taken up until the rise of Christian scripture in the first and second centuries AD. The development of Christianity took place over hundreds of years, and the New Testament was written, compiled, edited, and re-compiled time and time again.

When Christians met, they would read from these scriptures and debate and discuss them, and needed an easier way to reference the different texts which made up their growing written tradition. As I mentioned, with a scroll, you needed to unravel the whole scroll to find a particular passage, and then re-roll it when you were done. Parchment codices could fit a far larger amount of text and could have a table of contents and page numbers, making passages even easier to find and to verify against possible interference or interpolations. These codices could be made with papyrus, but increasingly parchment – created from the skins of animals and turned into a write-able material over a long process – was used for its increased durability. Durability was important for Christians, as was the increased portability of books, since they travelled far and wide across the Roman Empire and beyond to spread their message. By the end of the 2nd century AD, the codex was almost universal for Biblical texts.

Codices for non-Christian works were very rare. However, as the Roman Empire and its library, museum, educational, and political systems were worn down, and interest and ability to read texts waned, the advantages of the codex became more apparent for classical Greek works, too (which at this point could be referred to as “pagan”). Between less pagan literature being relevant, and the larger capacity of the codex, suddenly a vast amount of the corpus of perceived relevant pagan literature could be contained under a single cover.

And so began the vast transference of Greek (and Latin) literature from the papyrus roll to the parchment codex. This juncture is so critical in the transmission of Classical texts that countless works were lost forever for the simple reason that they weren’t in vogue during the centuries of transmission. The uptake of the codex and its superior, more durable technology, along with the impetus to transfer ancient texts onto the codices preserved the vast amount of texts that survive until today, which otherwise would have been lost from the high perishability and general unwieldy nature of papyrus rolls in a rapidly changing and unstable world. We still have most of the literature that survived this shift in some form.

However, it should be stated that just as important as the transmission of particularly Greek texts here, is the way that the Latin and classical Roman texts kept alive a spirit of interest in classical works during nearly a millennium of subdued engagement with those works in the medieval age in western and northern Europe. In the eastern Mediterranean, it’s likely many Greek texts could have been preserved through a more direct lineage, but in the west there were fewer Greek texts to copy. As I will discuss in a later article, fortunes were later reversed for the East when Greek learning diminished precipitously but due to a renewed appetite for classical Greek work in the west, it could be rescued and put to new uses.

The instability of the 2nd to 6th centuries AD took its toll on urban centres, which require highly sophisticated and literate economies of specialized classes. The institutions which relied on cities, like the centres of Greek literary, political, religious life since the ancient city-states of Greece a thousand years earlier, decayed too. This meant that as the ancient Greek and Roman periods came to a close, even the generally hardier codices would also vanish and disappear if not for a new institution: an institution that was designed to exist and persevere despite change, a stronghold of information and thought which will be discussed in the upcoming entry to this series.

Until next time…

If not for these innovations, which we still use today, the relatively tiny amouunt ofancient Greek texts that have reached us would not have. We still use writing, we still systematize and standardize writing, and we still use the book. These are major achievements which we are so accustomed to in our daily lives it can be easy to underappreciate them.

In the next entry in this series, I will continue this story with more innovations which are particularly connected with the Abrahamic cultural and religious traditions in the eastern Mediterranean. Those innovations, as you will see, also live on to today. One of the catalysts of this project will finally be answered, “why would Christians and others with an apparently different value and cultural system continue to copy and preserve ancient Greek texts?” I hope you will join me there.

To see which books and resources I used to research for this series on Ancient Greek Textual Transmission, please see here.