Why did early Christians and Muslims cherish Ancient Greek texts?

From monasteries to translation houses. (Transmission Pt. 3)

This is the third part of a series of articles on the transmission of Greek knowledge from antiquity to modern times. The first article covered an introduction to Ancient Greece, the second discussed the transmission of texts through antiquity.

In the previous entry on Greek texts during Antiquity (roughly 800BC-300AD), I described a linear process of how Greek works were transferred from oral cultures to written works, how those written works were collated, edited, and organized, and ultimately how the transfer of Greek texts from scroll to book helped save those writings from the grindings of time during the disintegration of the classical Roman Empire.

In this article, I will discuss how Christianity and Islam institutionalized into major political and cultural forces that threatened the continuation of Greek classical learning entirely. Yet I will also explain how, despite some major differences in worldview between the pagan works of the Greeks and the monotheistic religions, literate Christians and Muslims were also the ones responsible for the survival of ‘pagan’ texts which we know today.

“I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time.” - Thucydides, in his History of the Peloponnesian War, 5th century BC

There are momentous changes in late antiquity and the early Medieval period (300 to 1000AD) that politically and culturally cleave the world within which Greek works are a part. No longer were Greek texts transmitted primarily under a single Roman Empire. Greek texts are transmitted in two parts and then three parts under different administrations, with different religious backgrounds, and differing relationships with the Greek language.

Each of the three innovations that will be discussed here and their cultural milieus often existed during overlapping timelines. Before starting this article, some basic background information and geography is required to make sense of the context. The following maps depict the high-level political changes around the Mediterranean during the centuries of the innovations discussed in the article.

Innovation 4 - Monastery

And the development of Christianity

Since there are very few extant Greek texts from the ancient period, were it not for Christians copying and preserving ancient Greek texts we would have almost no remaining Greek texts at all. The important role Christians played in the transmission of classical Greek texts was the impetus that caused me to really dedicate myself to thoroughly exploring this. Wasn’t Christianity an entirely different religion and culture? Why would they continue to transmit texts from people that they may have seen as heretical, idol-worshiping, or otherwise dangerous? Even if they valued the technical expertise of their mathematics and logic, why would they preserve the literature of troupes of gods acting in abundantly morally questionable ways?

As Christianity developed and the religion eventually became the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380AD, Christians were faced with an acute dilemma of either excising classical Greek (and Roman) work from their society, or of finding a way to create a confluence of the different strains of thought. It was by no means guaranteed that Christianity would survive as it did in a politically volatile time so the early theologians of the Church needed to tread carefully.

Christianity emerged as a sect of Judaism, which at the time was uniquely monotheistic; Jews worshiped only one God, named Yahweh. This God was (and is) seen as omnipresent, unique, perfect, infinite, and both independent of and involved in the materiality of the universe. In Christianity this God essentially continued, but in three coequal figures of the Father, the Holy Spirit, and the Son (Jesus Christ) which is called the Trinity and was in fact a subject of much debate among Christians. The sacrifice of Jesus Christ to atone for all of humanity’s sins highlighted the fundamentally sinful nature of humanity and led to a Christian position of ideally acting humble and pious.

On the other hand, the Greek society that existed around the Jews and Christians was less strict in its worship and theology. This could manifest in several ways in literature. The poets of ancient Greek literature were polytheists who wrote about multiple gods and celebrated them, yet the gods often acted just as sinful as mortals and weren’t particularly edified. Mortals could be celebrated and filled with pride just as much as gods. Works on politics like rhetoric encouraged speech whose aims weren’t necessarily the ultimate, pious truth but their own aims for power. Even technical manuals on philosophy or science reflected a different way of viewing human’s place in the material and spiritual worlds and the truth they set out to uncover may lead to a spiritually corrupted un-Christian way of life. Furthermore, to continue to utilize such works could provide tacit approval and confidence to the remaining pagans and whatever institutions they may hope to revive. Newfound Christian confidence in their nascent institutions, such as monasteries, could be sapped out of Christians themselves as the achievements of pagans are again and again presented.

On the other hand, the strength of the work and thought of the ancient Greeks is clear in its very usefulness and the difficulty with which it would be to throw them away from one’s own life and practice, let alone that of the entire community you may lead. The community itself is likely not only a new Christian community, but still contains lots of pagans and people of other religious faith, and so discussing concepts of Christian faith using the tools of the Stoics, of Plato, and of other Classical works could appeal to non-Christians. Many Christians in this period were also converts to the religion and would have already been equated with pagan texts, and of course still found use of them. The youth of Christianity was clear in the relative lack of abundance of texts suitable for all purposes a community needs.

There was perceived to be utility in Classical works that can help one to understand the true axioms of Christian theological works. Models of Greek thinking from Plato and Aristotle in particular were used almost from the beginning of Christian time, with major Christian figures like Origen of Alexandria, Basil of Caesarea, Ambrose of Milan, and Benedict of Nursia using Greek philosophy to help explain and support Christian theology in a range of both western and eastern traditions of Christianity. Christianity continued to develop with elements of ancient Greek and Roman literature, religion, and science, albeit they needed some element of transformation and re-interpretation under the new Christian framework. In general, there was little outright censorship of ancient Greek texts, and the concern lay less on the fact that multiple gods were existing or on specific elements of theology, but on the potential to impart negative social values like pride and sexual deviance.

“In studying pagan lore one must discriminate between the helpful and the injurious, accepting the one, but closing one's ears to the siren song of the other.” St. Basil of Caesarea (AD 330-379), in his Address to Young Men on the Right Use of Greek Literature

Ultimately, the transition from ancient Greek and Roman governance structures and broader religious and cultural spheres to ones marked by Christianity was not a clear break. There were elements of continuity during this shift which took place over many centuries, and through all of that the vast suite of cultural traits and works would be seen as ‘theirs’ in a continuum that was not necessarily broken but continually developed. There was less conflict than you may expect between Christians and others, and in many cases ‘pagan’ texts weren’t seen as anti-Christian, even if they didn’t fully align with Christianity, but as perhaps neutral history. Texts didn’t have to be criticized or censored in order to disappear, simple neglect or lack of appreciation, as during the phase of transferring literature from papyrus rolls to parchment codices, could lead to their disappearance. If there were truly a wide-ranging policy of censorship against the ancient Greek literature among Christians, we would’ve lost all of it.

Now that we can understand how ancient Greek writing could be respected in Christianity in general, let’s take a look at it in a specific environment: the monastery. In the previous article, I mentioned how from the 2nd to 6th centuries AD urban centres began to decline, and because the institutions which supported Greek classical learning depended on these urban centres, those institutions all faded as well. Conversely, monasteries were built with rural sustainability in its DNA. Indeed, the word ‘monk’ comes from the Greek word for ‘monos’, meaning alone.

Early Christian ascetics began departing cities like Alexandria and its Library for a different method of learning: in quiet solitude and contemplation in the severe desert. One of these men in the 4th century was named St. Pachomius, who developed a model of communal living, which is now called Cenobitic Monasticism, whereby monks live and practice together while retaining their own space and time for private contemplation. Monasteries spread over Christendom, and although the interface between Greek texts and monasteries differed by region, this general Cenobitic type allowed for the preservation of texts in an environment of at least marginal literacy through oscillating centuries of change.

In the wake of the end of the Roman Empire in western Europe and the instability that resulted, the removed, self-sustaining collective model of monasticism worked well to steel its members against those changes. Monks weren’t lazily waiting, however. The most influential western monastic tradition was founded by St. Benedict in the 6th century, who created a set of “rules” regulating how monks should practice. The rules were flexible but encouraged activity and as such monks were teachers, students, farmers, bakers, stonemasons, gardeners, property managers, accountants, administrators, and many other professions.

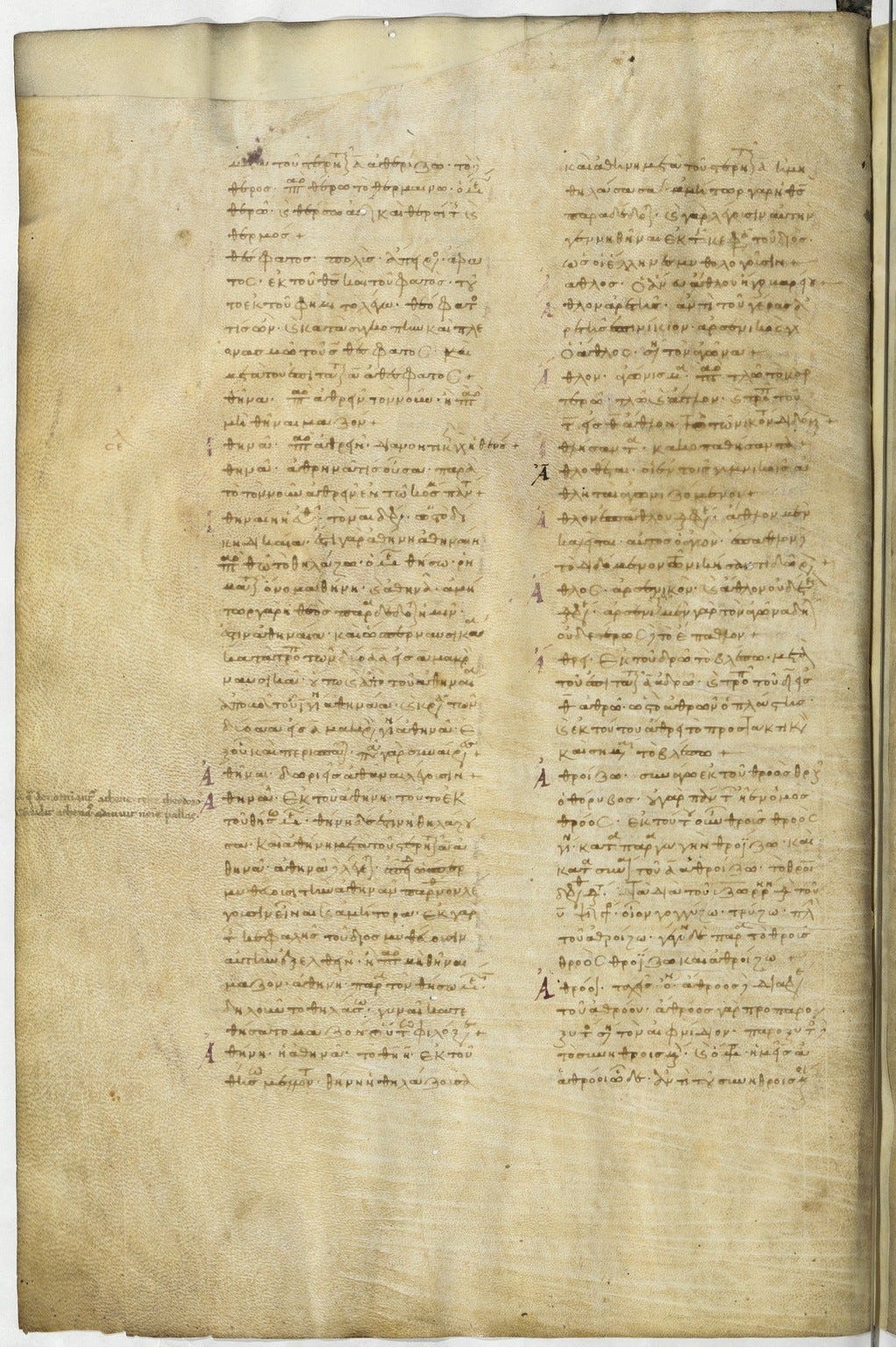

Benedict encouraged daily ready to be part of a monk’s practice, so books needed to be found, copied, and produced. Scriptoria, rooms in which scribes would copy and illustrate manuscripts, were a common feature of monasteries and this was the primary place of literary production in Europe until the printing press around a thousand years later. Through the chaos and general decline in reading of the period, books were eventually transferred from libraries of aristocrats to the retreats of monasteries as the monks living there were some of the last people with a culture available to appreciate those works.

The kind of reading to be done wasn’t specified by Benedict, and as such this is one way in which the openness of the rule allowed for a range of Classical oriented texts to be copied, although the primary works were Christian. In addition to non-Greek texts, there were some Greek texts in Latin translation that survived the end of antiquity, such as some of Aristotle’s texts and a few on philosophy and science which had been translated by a Roman senator Boethius at the turn of the 6th century AD. As there were overall hardly any Greek texts (even in Latin translation), the importance of the monastery in western and northern Europe for the transmission of Greek texts lies in them being the primary place of any kind of literary education in the early medieval period (5th to 9th centuries) and primarily in its Latin texts and the small teases of Greek material which kept classical interest alive for times later in the future when they would be able to receive them, identify them, translate them, and eventually incorporate them in traditions later on.

From the perspective of later countries like Britain, France, Germany, and Italy, Greek texts were essentially lost for the medieval period and were ‘rediscovered’ in the renaissance. So how did they come across the Greek texts, where did they come from if they weren’t preserved in their own regions? For that story, let’s head to the eastern Mediterranean.

Innovation 5 - Miniscule Script

And the Greek Roman Byzantines

The instability which faced the Western Roman empire was not as acute in the Eastern empire. The Roman empire began splitting up in the 3rd century, and after 286AD, the city of Rome would never again be a capital of the Roman empire. At one time there were as many as four capitals for different regions of the empire, but by 323AD the power was once again concentrated in a single city: New Rome. New Rome, in what is today Istanbul in Turkey, was called Constantinople after the empire’s first Christian emperor, Constantine. Instability soon returned, and in 395AD the Roman Empire split into a western half and an eastern half, where Constantinople remained as the capital. The Western Roman Empire continued to dissolve, and in 476AD all of the imperial insignia of the crown of the Roman Empire was sent to Constantinople, where the Eastern Roman Empire remained strong and stable enough to support a direct line of Roman emperors until 1453AD.

A note on terminology: “Eastern Roman Empire” can be used interchangeably with “Byzantine Empire” and “Byzantium”. The word Byzantine came into use after the 16th century, and especially in the 19th century when it became the widely accepted term to differentiate from the earlier periods of the Roman Empire and somewhat to denigrate the medieval Greek-led Roman Empire as opposed to the earlier Latin-led Romans. In fact, the “Byzantine Empire” called itself the “Roman Empire” (Imperium Romanum in Latin and Basileia ton Romaion in Greek) and called themselves Romaioi, as did many Greeks until the 19th century.

Along with the imperial continuum the technologies and institutions within which Greek texts were created and preserved -- like writing, libraries, books, and monasteries -- continued in a recognizable form unlike in western Europe. Furthermore, although there were many non-Greeks in the empire, Greek remained the most spoken language of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Christianity that formed under the Roman Empire continued to develop.

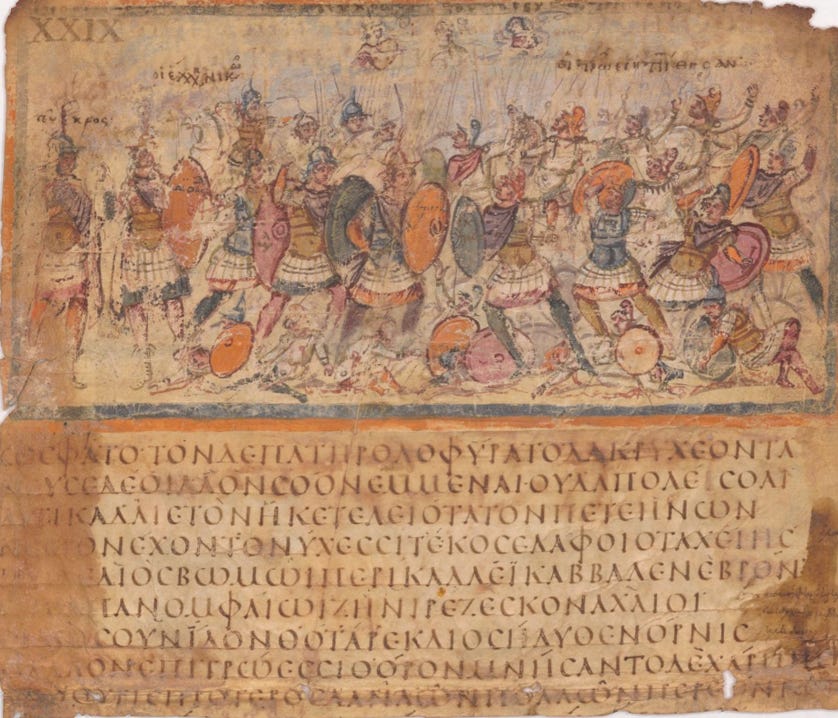

These factors produced a society which was uniquely Greek, Roman, and Christian unlike anywhere else before and since. Greek classical texts remained socially and intellectually prestigious as links to their already ancient past, yet they could also be religiously dangerous in the Christian state. Grappling with these circumstances, the scholars of the Byzantine Empire produced material that is almost unarguably the most important factor in the transmission of Greek classical texts.

The material produced was so wide-ranging and decisive for our modern view of Ancient Greece that in a sense, when we engage with Ancient Greece we do so almost fully through the lens of the Byzantines after the 9th century AD, when they experienced their own Renaissance of Greek classical learning. This period was marked by the creation of the Miniscule script, as opposed to the Majuscule script which had until then been the dominant script (‘script’ as in a type of font). To understand why something as seemingly unimportant as a script could have such major ramifications, I need to explain the economic and political events of the preceding centuries.

In the 5th and 6th centuries in the Byzantine Empire, learning flourished as stability and power was projected across the empire and beyond, with the newly constructed cathedral of Agia Sophia drawing on excellence in geometry and mathematics to construct its magnificent dome. Many libraries and schools had their collections transferred to the imperial university and library in Constantinople and its monasteries. Following this, in the 7th and 8th centuries a controversy within Christian theology soon took all the attention in the empire and interest and use of Greek texts declined significantly.

The controversy was called Iconoclasm. Iconoclasm was a movement against the use of icons to worship and venerate God and saints of the church. It can hardly be overstated the importance of this movement, as church artworks were destroyed and theological arguments debated. Interest in ancient Greek texts declined across the empire, with only a few exemplar texts receiving new copies. Scholars did scour the libraries, however, looking mainly for texts that would support their views in the iconoclast controversy.

As the iconoclasm controversy continued, the Islamic religion grew rapidly in Arabia just to the south of the empire’s holdings in the Middle East. Within a century, the Islamic Caliphate had conquered huge tracts of the Byzantine Empire, including Egypt where most of the papyrus was grown for writing material and grain was grown to feed the empire. Relations were not cordial between these powers and trade was limited, so at the same time as the Byzantine Empire was already economically unstable from the iconoclasm controversy, they lost a huge food source and their cheaper writing source was unavailable.

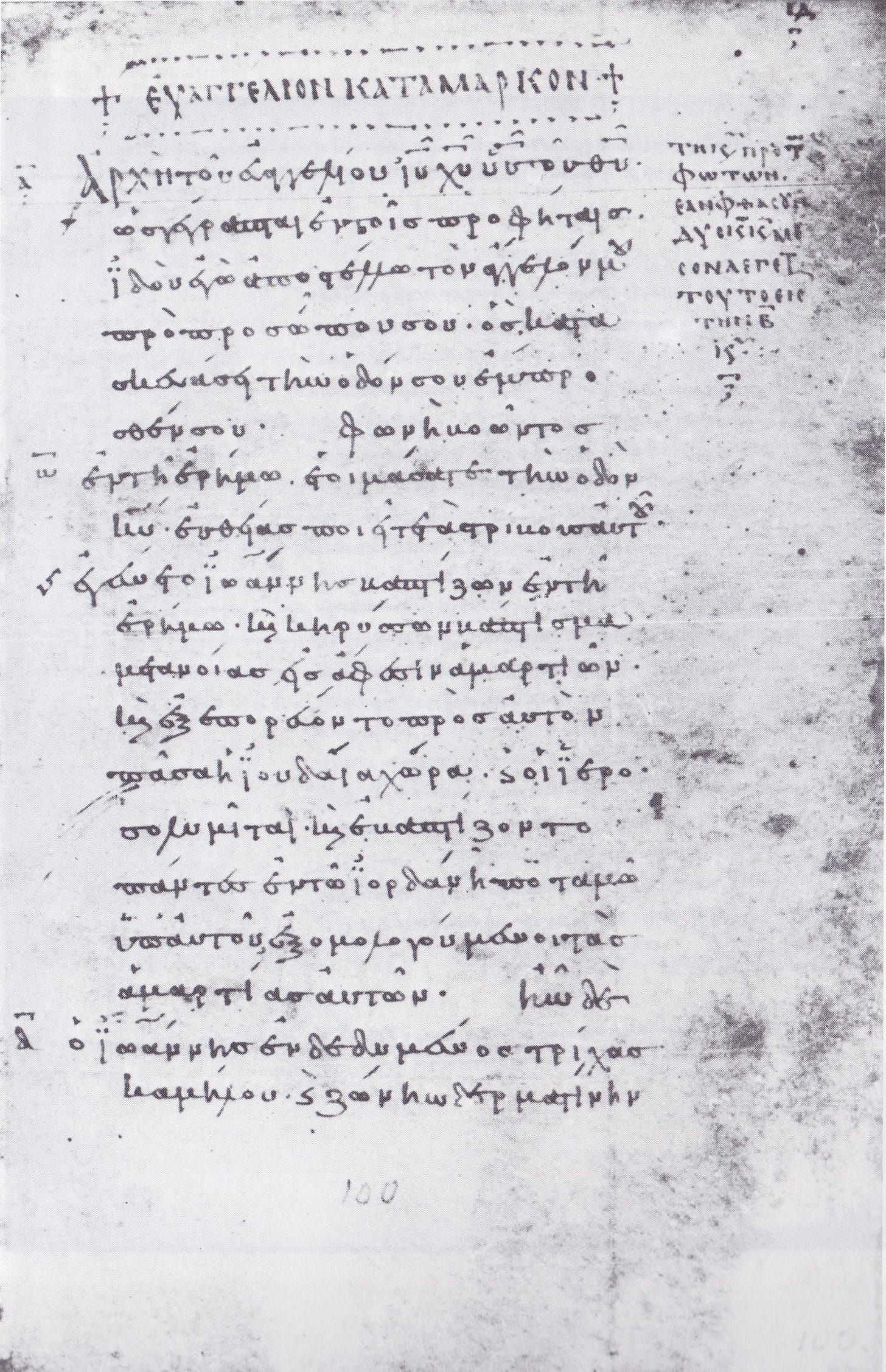

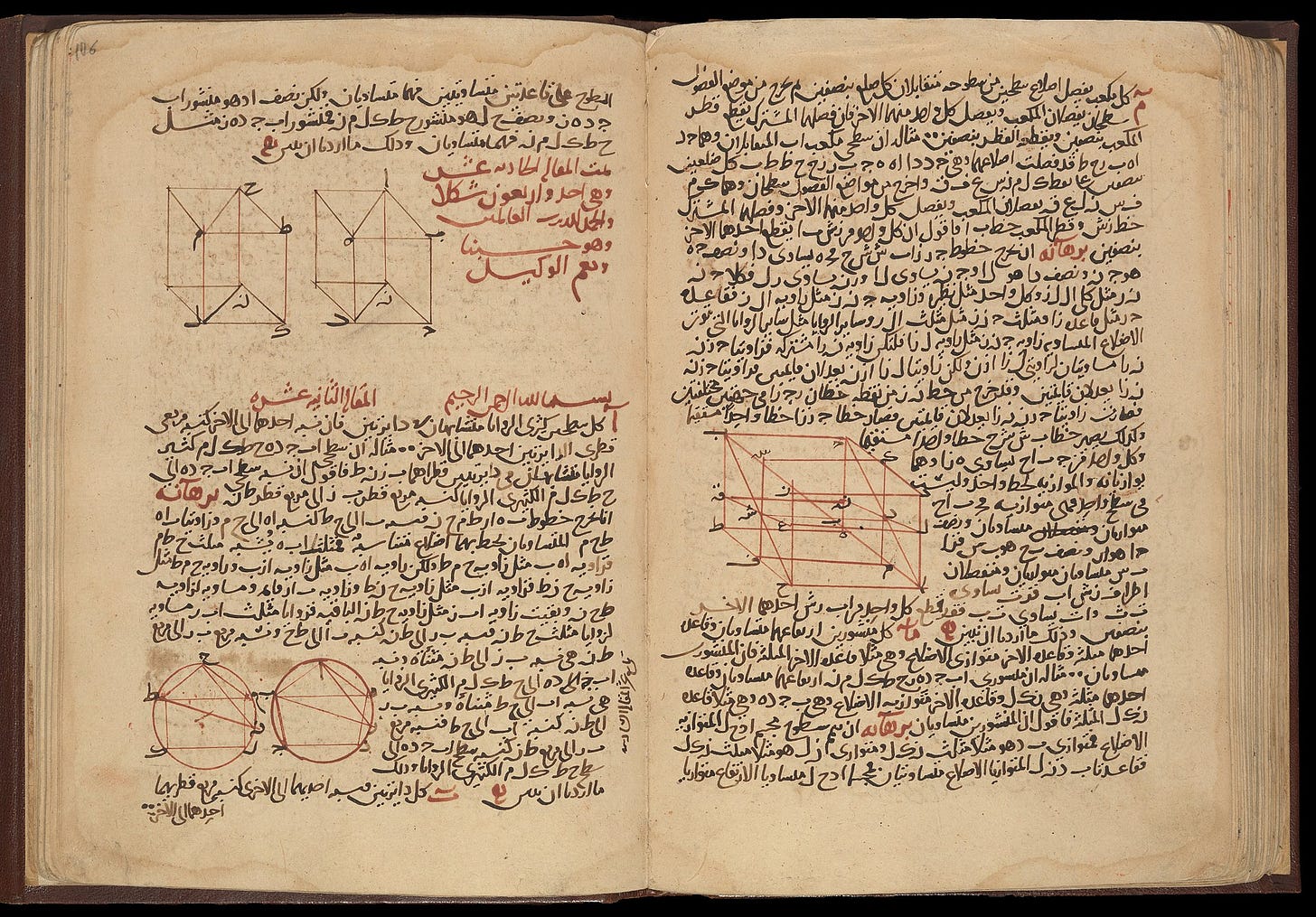

Even during turbulent times with a lower interest in reading and studying, theological texts were needed for the church and administrative texts for the state. The Majuscule script which had been used since antiquity was slow to write and the large letters took up a lot of space on the page, making writing an expensive endeavour. To save space on the page and write quickly, a smaller form of text was devised in Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople, which we call the Miniscule script. The first example we have of this type of text is from 835 when the Miniscule script was clearly already well developed. A new script may not seem groundbreaking in our world filled with text and limitless digital options for sharing information, but making a book of parchment was a months long endeavor that costed dozens of animal hides to produce; no mean feat during economic and military conflicts.

Fortunately, the iconoclast controversy was finally solved in the late 8th century and the empire stabilized, albeit much smaller (mainly taking up the land of only modern-day Greece and Turkey). In this time of enhanced prosperity and peace, a renaissance of interest in ancient Greek work was ignited which would have been impossible without the development of this miniscule script. During the troubling centuries of iconoclasm and invasion, many texts were destroyed or their text rubbed off and written over with new texts to justify one side or the other of the iconoclasm conflict. By the 9th century, in some cases there remained just one copy of a particular text.

Similar to what occurred in the 2nd to 4th centuries AD when texts from scrolls were transferred to books, a huge amount of texts were copied in the newly developed minuscule script. Because so many of the important texts across the empire had been transferred to Constantinople before the Islamic invasions, the monasteries, schools, libraries, civil service, and court could all work together in synthesis to advance the learning and copying of these texts. The two scripts can not be compared with our Latin alphabet’s form of upper-case and lower-case, as the Majuscule and Miniscule scripts were radically different. This led to a need for guides on how to use the Miniscule script and much discussion on the Greek language in this period.

Beyond this simple utilitarian need for a compact script belies the true reason scholars, monks, and emperors were still fascinated with classical Greek texts: rhetoric. Today, Greek texts are plumbed for their information about the life of the ancients, their narrative structures are examined to understand the religion and politics of the day, and philosophical and mathematical texts studied to better understand our own intellectual traditions. However, for the Byzantines, as for the original Greek writers in the 5th century BC, the oral culture of rhetoric was incredibly important. They studied and memorized ancient Greek and attempted to emulate this style of speaking which was perceived as truly the pinnacle of human expression in the public sphere. The obsession with speaking well continued right through the Roman period and even until the late Byzantine period.

However, the dialect of the ancient Greek language of Athens in the 5th century BC, called Attic, had already been ancient and archaic even in earlier Roman times. ‘Atticism’ is the term for the tradition within which people consciously tried to recapture the magic and truth of the ancient Greeks in Byzantine times. The form and the style of the language had a tradition as the most important, even in generating new meaning for Christian work. This is well exemplified by a quote written in the margins of a 13th century copy of a Christian text called John the Gospel, wherein the use of Homeric language and meter is justified.

“We should note that the reading of Hellenic literature has always been an object of longing and delight for lovers of learning, and particularly the reading of the poems of Homer, because of the grace and variety of the language. That is why the present metrical paraphrase has been written in heroic [Homeric] meter, to give pleasure to lovers of learning and literature.” – Maximus Planudes, Byzantine scholar writing in a 1299AD edition of John the Gospel (Marc. Gr 481), produced at the Monastery of Apokaleptos in Constantinople

To try and achieve the goal of achieving the best form of writing, lexicons, dictionaries, and etymologies – as well as basic word spacing and diacritical marks – were created which helped the Byzantines learn to read, write, pronounce, and speak with an Attic dialect. This study of the ancient forms of their own language, as well as vociferous reading and copying of old manuscripts, was also necessary in order to understand the truth of what was actually said. In essence, there was nearly a direct relay baton pass from the Library of Alexandria in the 3rd to 1st centuries BC to the libraries of Constantinople in the 9th to 15th centuries AD. The commentaries and notes of the Alexandrians were judiciously copied along with the original texts in the margins of the pages and different manuscripts were compared to see where they differed, and critical texts and editions were produced based on these collated findings.

It wasn’t just scholars engaging with ancient Greek texts, but even young students learned to read Greek with the archaic and distant Homeric poems like the Iliad. There was no basic educational literature, nor was it deemed appropriate to learn from the Christian material, so children had to wade through the thickets of the ancient poets to learn to read. Many of the extant texts we have were of the specific types taught to students.

In addition to looking backwards to their own past, the Byzantines’ achievements were projected in the future right down to our own day as well. In effect, they are the middle point of this journey, balanced between the origins of Greek oral and writing traditions and our modern study and understanding of ancient Greece. Almost our entire library of Greek texts is a result of the selections and exclusions of the Byzantines. The critical apparatus used to read, understand, and categorize Greek texts was largely designed by the Byzantines, and scholars today work in their academic tradition. If it wasn’t for their dictionaries and lexicons we wouldn’t know how ancient Greek was pronounced. If it wasn’t for their commentaries and copies of ancient texts, we wouldn’t even know what the ancients had said at all.

In fact, almost our entire library of ancient Greek texts is composed of that library of texts which the Byzantines were most interested in for education and rhetoric. A Christian patriarch in the 9th century AD, Photius, wrote a review and bibliography of 279 texts he had read (The Bibliotheca), about half of which are no longer extant in any form, and this is how we know of many texts that perished in the centuries before anyone could copy them and continue their transmission. And so, an existing manuscript from this period is usually the oldest extant version we have. When you read that an ancient Greek in the 5th century BC ‘said’ or ‘wrote’ something, you are usually taking the word of a late medieval Byzantine monk or scholar for it. Or a young student.

But what about an Islamic culture that on the face of it is neither Greek, Roman, nor Christian? How do they become an important part of this story?

Innovation 6 - Translation

And the spread of Islam

Islam is another step further removed from the Classical Greek world as Christianity was. Islam’s founding prophet Mohamed and the region in which the religion first flourished – in mid-Arabia – was over 1000km southeast of the Mediterranean in Mecca, a region that was never part of any Greek or Roman polity. It’s primary and sacred language is Arabic, which is very different from Greek or Latin. When the religion was founded in the 7th century and spread throughout the 8th century, classical Greek and Latin knowledge was at its lowest point in history since then and until today. In western Europe, few Greek texts survived to be read even if there was anyone to read them. In the Byzantine east, the Christian theological arguments of icon worship left little time for classical learning. There was little chance of cross-cultural sharing of Greek knowledge in this period. Additionally, there are elements within Islam that would seem conflict with Greek work, such as Islam’s monotheism and its stringent ban on visual representation of divinity.

Yet, in some ways, there was incredibly deep engagement with some Greek texts by Muslims and others living within the Islamic-controlled regions in the 8th to 12th centuries AD. How and why did this happen?

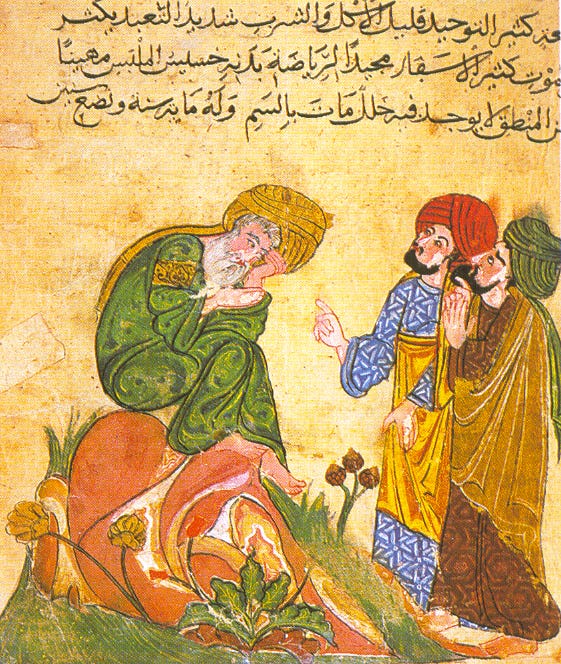

Just like when Christianity seemed to be at odds with Greek work, there are spaces of potential confluence between Islam and elements of Greek thought. For instance, there are injunctions stated in the Islamic holy book, the Quran, which place high emphasis on acquiring and developing knowledge. But the religion itself isn’t the primary reason for the uptake of Greek work. During the first spread of Islam and its first two caliphates (roughly translatable as “kingdom”), which stretched from the religion’s founder Mohamed in 622 until 750, there wasn’t a particularly high interest in Greek work. In 750, the Abbasid Caliphate came to power, established a university-like House of Wisdom in Baghdad, and engagement with classical Greek work flourished.

There were several reasons for renewed interest in Greek texts in this period. First, as with any new institution such as Islam, there were conflicts and disagreements which led to political and then philosophical discussions about what a ‘Caliphate’ is and how their polity would be governed. For example, should the leader, the caliph, be an elected or hereditary post? To help settle such questions, texts from across their massive conquered caliphate were drawn upon. This included the Persians, the Mesopotamians, the Syrians, the Egyptians, and of course, the Greeks.

It was mentioned in previous articles that since Alexander the Great’s invasion of much of the Middle East in the 320s BC (1,000 years prior to the advent of Islam) that Greek influence in politics, language, philosophy, and science were firmly established in the region. Although Mohamed and the Arabs who founded Islam were not from an area that was part of a Roman or Greek polity, major centres of Greek learning and of Greek-inflected Christian developments in Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem were now part of an Islamic caliphate. Greeks and people proficient in Greek continued to live in these same regions, simply under new leadership (as did Christians and other non-Arabs and non-Muslims who still remained the majority).

Just as importantly, “Greek” texts no longer had to be in the Greek language or even viewed as the providence of ethnic Greek people. During the period of the Eastern Roman Empire, a major translation effort had been established to translate Greek pre-Christian and Christian texts into Syriac, which was a major language of the Middle East and its diverging Christian tradition. The pre-islamic Persians, who had been incorporating Greek thought into their ideology since Alexander’s time, sometimes claimed Greek texts were part of their own religion (Zoroastrianism) that had been destroyed and dispersed during Alexander’s invasion and they were simply ‘re-translating’ them into Persian.

By the time of the Abbasid caliphate in the 8th century, they had a vast empire within which they tried to restore not Roman rule, but Persian and Mesopotamian ones. Greek works were then inherited as their own: as works created in their lands, in their languages, and as part of their pre-Christian and Christian religions.

Beyond simple identity, the Greek texts were put to significant use after being in confluence with Mesopotamian, Persian, and Indian astrology and mathematics. They were all translated into Arabic and learning at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad flourished to support the empire which needed fields like geometry for their agriculture and trade. The Islamic world ultimately advanced Greek math and developed the fields of algebra and trigonometry.

At times they even contrasted their inheritance of Greek identity with that of the Byzantines, and claimed that despite the Byzantines being a primarily Greek-speaking empire, they were in fact Roman (and as we have seen, the Byzantines did consider themselves Roman). As 9th century AD essayist al-Jahiz stated, the Abbasid caliphate could be considered the rightful heirs of the classical Greeks due to their advancements in philosophy, math, and medicine.

“[The classical Greeks were] individuals of one nation; they have perished but the traces of their minds live on: they are the Greeks. Their religion was different from the religion of the Romans, and their culture was different from the culture of the Romans. They were scientists, while these people [the Romans, i.e. the Byzantines] are artisans who appropriated the books of the Greeks on account of geographical proximity . . . [claiming] that the Greeks were but one of the Roman tribes.”

If we had lost all of the Byzantine manuscripts, we would have an extremely narrow view of ancient Greece. However, through Arab scholarship, Greek science, math, and some philosophy would have had a chance to survive and without this process of translation many works of Greek math likely would have never have survived. The uptake of a new technology also assisted in the survival of these Greek works.

At the eastern end of the Islamic world they learned how to produce paper from the bordering Chinese, which was a technology cheaper and easier to produce than parchment yet more durable than papyrus. The wealth of the Islamic caliphate and this new technology meant the texts from this Arab scholarship, including that of the Greeks and the advancements the Arab scholarship made, could be moved swiftly across the vast Islamic world from Central Asia to Iberia in Western Europe.

It is in Islamic Iberia in Western Europe that this story will continue in the next article.

Conclusion

Each of the three innovations discussed here come out of a tradition that can claim some continuation of the Roman Empire or even the classical Greek past. Although they diverted, in the next article the intellectual traditions will once again unite in a single thread that stretches to today.

We still have monasteries much the same as they were. We still use more and more adaptable and easy fonts with which to better share and create information. And we still translate and share texts with other cultures and groups in order to innovate and rejuvenate with fresh eyes. The next article, the final entry in this timeline, will continue to build on these innovations.

To see which books and resources I used to research for this series on Ancient Greek Textual Transmission, please see here.

I also wonder how much the flight of the Academy to the East after proscription may have fed this interest?