The Threatened Survival of Ancient Texts

Greek literature exists due to recurrent utility, not material preservation

This month’s guest post is an essay by James Binks.

James Binks is an independent scholar based in Canada and Greece. He makes his living conducting museum-based research on Western Canadian history, as a tour guide, and as a scuba divemaster. He seeks to answer the question “How do we know what the ancient Greeks said?” by writing about the material evidence of the long transmission of Greek literature at Culture Cross.

In the ancient Mediterranean world, kings and warriors travelled great distances to consult with the god Apollo. After a perilous journey to his temple perched high and hidden at Delphi in the Parnassian mountains, visitors would need to wait until one of nine annual days in which the god’s intermediary, an oracle known as the Pythia, was available to provide guidance on which direction to take their lives. Even then, only if the sacrificial goat brought to the temple doorstep shivered when doused with water would the day of consultation with the oracle be ushered in.

After the payment of a fee, the visitor would make their way towards the sanctuary. Inside the darkened temple, the consultant likely couldn’t make out the Pythia behind her wall as he framed his question. If the consultant was made aware of the local tradition, he would frame his question as though he were looking for advice: Which path should I take? Which action need I take to ensure my future?

The oracle would then breathe in the ‘pneuma’ – the breath of inspiration – which filled her room with a delightful fragrance. Through her poetic meter, the god Apollo reflected the truth off the jagged walls of fate. This advice was ambiguous but powerful. Visitors often sought further remediation back home – sometimes taking months to sift through the possibilities of the prophecy to reach the true meaning.

Sources of Greek Literature

The future has always been a matter of concern and wonder for all people. At times, people grapple directly with their uncertain futures, whether through prophecies at Delphi, astrological readings, or a local weather forecaster. Although the future is clearly unknown, stories such as the one recounted above – commonly provided by tour guides, guidebooks, and academic texts about the ancient site and its oracle at Delphi – make the past seem misleadingly clear. It is shrouded in the same uncertainty as times to come.

How do we know what happened in Delphi thousands of years ago? How can the alleged deeds, words, and thoughts of ancient Greeks still be heard thousands of years later?

The story recounted above is a pastiche of several short literary texts from Plutarch, a priest of the Temple of Apollo in Delphi around 95AD. Plutarch was one of the most prolific Greek writers of the ancient world, and many of his texts discuss the oracle at Delphi, primarily in a body of work we now call Moralia. Despite living hundreds of years after most of the famous prophecies at Delphi were allegedly given, Plutarch’s texts are the most important source for information on how the oracular process was completed.

However, just as Plutarch’s Delphic stories tell of trepidation and tradition in trying to determine the future, so too are the paths to knowing the past full of debates and traditions of our forebears.

No texts from Plutarch’s own hands (or his scribe’s) – also known as an ‘autograph’ – exist. The earliest surviving material evidence of any part of the story from Plutarch I recounted is a tiny papyrus fragment from at least several decades after his life. The oldest extant – that is, still surviving – material that contains Plutarch’s full Moralia texts concerning Delphi and the oracle is in a manuscript referred to as Parisinus 1672, from the 14th century, more than 1,200 years after the alleged time of composition of Plutarch’s works.

The lack of Plutarch’s own writings on Delphi are not an exception; we don’t have any autographs of ancient Greek literature. The earliest material evidence of Greek literature is often from centuries or even a millennium after the alleged initial composition of the text in the form of copies, quotations, or approximations of the original text.

To be able to deduce when Plutarch or any ancient Greek lived and to discover what they wrote requires complex layers of deduction, discovery, and comparison of historical textual fragments, manuscripts, and books spanning the centuries between the author’s life and today. This process crisscrosses all the traditions and geographies that received, influenced, and produced those works.

Verba Volent, Scripta Manent

Spoken words perish, yet writing remains. Unlike some cultures, such as the Vedic tradition that has been able to preserve many texts in South Asia through oral transmission, most societies around the Mediterranean shores have utilized the materiality of writing to help transmit their texts. Through the grinding millennia of their societies’ cultural transformations, ancient Greek texts would have held no chance of surviving until today without writing.

In our future beyond the future of the Delphic oracle’s prophecies, we can peer backward through the layering mists of our past by focusing our lens not just on the ‘texts’ as such, but on the actual surviving (i.e. extant) material remains of those texts – primarily in papyri fragments and parchment manuscripts. Looking at the chronological attestation of the oldest fragments of Greek texts and the oldest manuscripts that contain a complete versions of those texts reveals two patterns: most of the extant oldest fragments were written on papyrus between the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD in Egypt, and almost all the extant complete versions of the texts were written in the form of a codex in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire after the 9th century AD.

Peeking into the historical processes of the production and preservation of these material remains sheds light on why and how ancient Greek words kept being written down despite the challenges, and explains why many texts didn’t survive. Indeed, the fundamental nature of materiality and decay means that texts are always at risk of not being transmitted into the future. Even today Greek texts are at threat of being lost forever in our own future. After all, written words perish, too.

Utility and Technology of Greek Texts

Christian Philosophy and the Codex

If one could ask the Delphic oracle today which action they might take to ensure the everlasting life of ancient Greek literature, her response may not be immediately clear, but I suspect it would include the word “utility”. To understand why, let’s follow the trail of extant Greek texts, starting with the oldest surviving complete manuscripts.

At the end of the 1st century AD, when Plutarch was a priest at the Temple of Apollo, most of the texts of the Christian New Testament were being written down and compiled. The eastern part of the Roman Empire, including the province of Judea where Jesus of Nazareth and his disciples began to spread their word, had Greek as its lingua franca for administration and scholarship. As such, the gospels of Jesus’ life, the letters of his Apostles, and other books that make up the New Testament were first written in Greek in the decades after Jesus’ life.

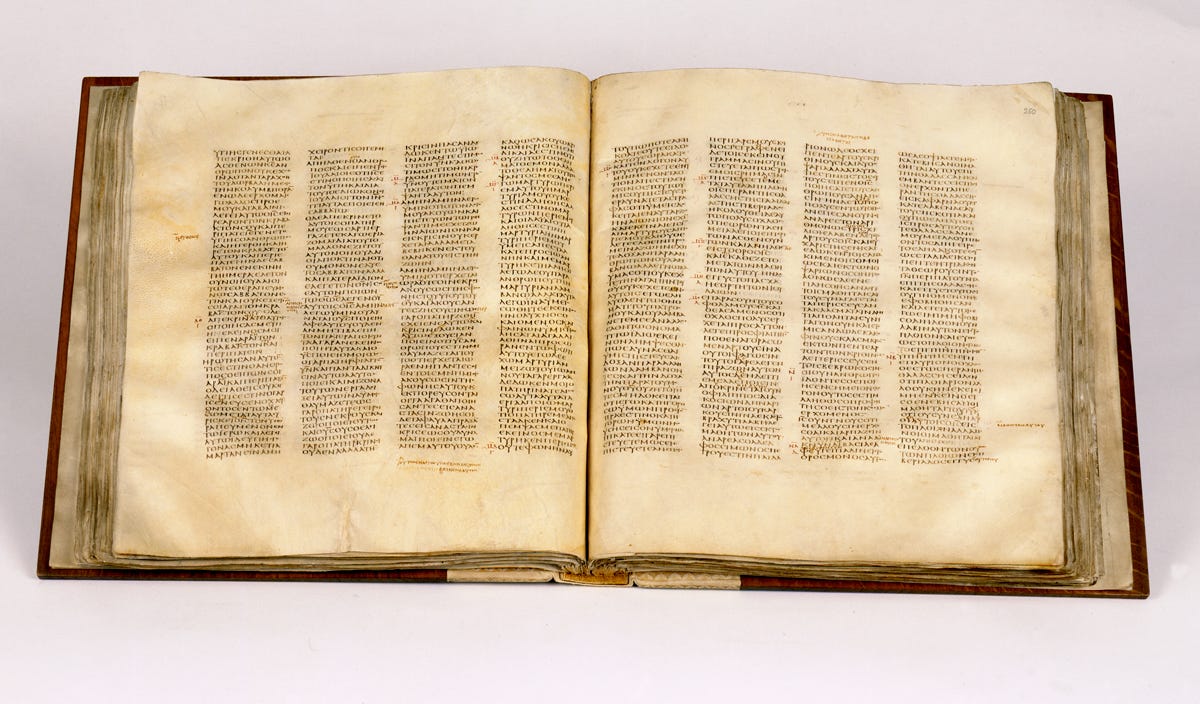

One of the earliest complete attestations of an ancient Greek text is the Codex Sinaiticus, from the 4th century AD. The Codex Sinaiticus contains the 27 books that make up the canon of most Christian communities’ Biblical tradition. This manuscript is far older than most other extant complete ancient Greek texts due to the greater number of Bibles copied compared to other literature during that period, and because Christians essentially invented the technology of the codex.

A codex is basically a book as we know it today. It is composed of sheets of papyrus, parchment, or paper that are stacked and then bound together along one edge. The first codices were made with the stem of the papyrus plant, but increasingly parchment – which is made from the skin of animals – was used for its increased durability. The nature of the codex was perfectly suitable for the Christian scripture; not only could it contain far more writing than the previously dominant media, the scroll, but it was far easier to open to a specific reference in the text without needing to unroll and reroll a scroll. Referencing specific verses in the Bible was an important utility in early Christian communities.

The cosmological orientation of the early Christians was not anchored to a location, a set of ritual implements, or a defined set of people. Instead, Biblical codices were their primary religious materials. As the universal, proselytizing Christian faith gained converts along the networks of the Roman Empire, it brought elements of ancient Greek culture with it. Not only was the New Testament a Greek-language text, but the broader Greek culture was the conduit through which poetry, philosophy, medicine, politics, geography, logic, and education had been expressed for centuries. Although there were ways in which the theology of Christianity was at odds with the polytheistic Hellenistic practices, to survive, the nascent Christian religion had no option but to continually remain in dialogue with its own past, be it Greek, Jewish, or otherwise. To make one example, many of Plato’s texts were swept up in Christian theological debates on the relationship between physical and transcendental knowledge (if Jesus is God made flesh, does that mean perfect omniscient knowledge can exist in the physical world?).

In other words, pre-Christian Greek literature was too useful and too embedded to ignore. The same would later become true for Christian literature, and nested inside those texts, a certain element of Greek culture.

Theological debates, which often referenced ancient Greek texts, would continue to hold sway as Christianity was made the official religion of the Roman Empire, which continued on as a theocracy in the Eastern Roman Empire (generally referred to as the Byzantine Empire today) from the time of the Codex Sinaiticus in the 4th century until the 15th century.

Within this polity, institutions like libraries and schools which had previously created and nourished Greek texts declined due to economic instability and cultural change from the 5th to 9th centuries AD. Literacy and learning largely moved into Christian monasteries, which is where many manuscripts, both Christian and not, were copied. If it weren’t for the conscious efforts of Christian scribes – effort expended due to the utility of the information encoded within – we would have almost no ancient Greek texts at all.

Greek Ethnicity and Miniscule Script

It wasn’t only in explicitly Christian contexts where the Greek texts were created. The Byzantine Empire was primarily Greek in ethnicity and culture writ large. After all, students learned to read and write not with a basic pedagogical text or a Christian one, but through the already-ancient Iliad! In their capital Constantinople, ancient Greek statues like Herakles adorned their hippodrome well into the second millennium and the people continued to engage with the myths of their ancestors, even if stripped of their explicit religious content. They also continued to treasure many forms of the Greek language in their literature, especially the “Classical” Attic form of Greek writing and speaking, which were esteemed in a culture that highly valued the potent power of rhetoric.

Because the everyday Greek of a Byzantine subject had transformed dramatically in the centuries since the ancient Greek texts they utilized, a significant proportion of classical Greek texts that survive are a result of the Byzantines themselves attempting to understand and pronounce the ancient ways of the Greek language.

There is a preponderance of extant complete manuscripts from the 9th century onwards because after theological debates within Christianity were resolved, that energy could be redirected towards copying Greek texts afresh in the new schools, monasteries, and libraries constructed from improving economic fortunes. However, with papyrus increasingly hard to come by after Byzantium lost Egypt, the more expensive parchment needed to be used for new copies. To save time and space during the copying process, a new script called miniscule (roughly a lower-case type) was devised to partially replace the older majuscule (upper-case) script, which also had the benefit of more clearly being able to convey ancient Greek pronunciation due to its additional punctuation.

The Byzantine parchment manuscripts written with miniscule script, which contain texts that survived the bottleneck of transference from one copy to another due to their theological and cultural utility, are so decisive for the extant canon of ancient Greek texts that when we engage with literature “from ancient Greece” we do so, essentially, via the texts deemed valuable and copied by Byzantine scribes who in most cases are closer in time to us than to the ancient Greeks.

Science and the Printing Press

As the Byzantine Empire was the most important polity through which ancient Greek texts were utilized and preserved, when it was conquered by the Ottomans in the 1400s, bringing an end to a millennium and a half of Roman Emperors, it brought the continuation of ancient Greek texts under duress. In Western Europe, Greek literature was lost after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and the resulting economic ruptures and decline in literacy. The only Greek texts remaining in Western Europe were a few excerpts of Aristotle in a Latin translation.

However, to the east and south, teams of scholars in Baghdad had translated Greek texts into Arabic to help support the new Islamic religion and its caliphates expand as far as Iberia. Arabic-language texts based on the original Greek like Galen’s development of medicine, Euclid’s geometry, and Aristotle’s work on logic were then made accessible to the English, French, Italians, and others after Christians reconquered Iberia in the 13th century AD. Therefore, just as the Byzantine Empire was in decline, Western Europeans were rediscovering Greek literature. Italians in particular could take advantage of the situation in Byzantium by absorbing incoming Greek manuscripts and scholars fleeing the crumbling Empire.

The knowledge gained from Greek texts and the culture of scholarship in Western Europe resulted in the invention of new technologies, namely, the printing press. The ease of printing led to the explosion in the output of book production, including the first printed edition of Greek texts. Great wisdom and unsurpassed knowledge could be found in ancient Greek literature. With the utility of these works such as Aristotle’s Organon (which translates as “tools”) – a treatise on the production of knowledge through material observation and philosophical introspection – the advancement in knowledge could be turned against Greek thinking itself. The paragons of Greek thinking were slowly pried open, isolated, and picked apart as time went on. Francis Bacon went on to publish the “New Organon” in 1620, and Aristotle was the first casualty. Bacon laid the groundwork for the scientific revolution, which although undeniably influenced by ancient Greek conceptions of knowledge, went far beyond what the ancients were capable of. As the modern age was ushered in, many Greek texts were no longer the best in class, thereby losing one of their key utilities.

Material Transmission of Greek Texts

Threads of Scholarship

We only know ancient Greeks through much less ancient copies of their works, copies that were made not simply for the sake of conservation. Rather, their creation followed a specific, pressing utility involved in the texts. Texts weren’t copied and preserved for the future, or for historiography, but for their own time.

Although manuscripts were created to address and improve some condition of the present, they usually weren’t just ephemeral tools. Manuscripts were important materials and were treated with the utmost respect. Therefore, they stood a chance to last for centuries. However, this still means that during the moments of transference, such as from papyrus scroll to codex, or miniscule to majuscule script, or handmade manuscript to printed book, the texts which didn’t have utility in that moment were copied more sparingly and sometimes lost entirely.

The prospect of lost texts and politics of transference begins to reveal the 2,500 year-long process of Greek textual history as more complicated than the simple chain of transmission I have presented so far. For instance, the oldest extant material of a text isn’t always the most reliable indicator of the initial ‘autograph’ of an ancient author. The oldest extant complete version (aside from 42 omitted lines) of Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations is the Vaticanus Graecus 1950 manuscript from the 14th century. However, most modern editions consider the first printed edition of Meditations by Wilhelm Xylander from the 1550s to be more reliable and authentic to Marcus Aurelius’ original. This printed book was based on an older Byzantine manuscript that is now lost because after it was used as a model to be printed from, in the mind of Xylander the manuscript had lost its utility and was discarded.

This discussion introduces the reality that for most of the textual history of ancient Greek texts, there were multiple threads of transmission. Unlike the global scholarly community of today, scholars were disparate throughout the world with less access to texts and little awareness of the texts other scribes possessed. As scribes copied the ‘same’ text independently of one another, they inevitably introduced their own mistakes through editing the texts. These mistakes could be compounded as time went on and the paths of transmission continued to split.

Additionally, just as Christians copied Plato for their theology, Arabs copied Galen for their medicine, and Italians copied Aristotle to support their universities, Greek texts weren’t copied and re-created just for the sake of it. Rather, this textual tradition took place inside different milieus of utility which were produced through debate and therefore most manuscripts contain various notes and commentaries, either from the scribe himself or a completely different text, which help illuminate various meanings of the primary text.

This process of scholarship shows how it’s not immediately clear at what stage a text is complete or when it’s missing sections. Therefore, even when a manuscript of a text is ‘complete’, that doesn’t mean it can simply be read at face value as the whole work as expressed by the ancient author. Different manuscripts, commentaries on texts, notes, fragments of texts, and quotations need to be cross referenced from the thousands of years of scholarship to best understand what was originally written in the past.

Preservation of Papyri

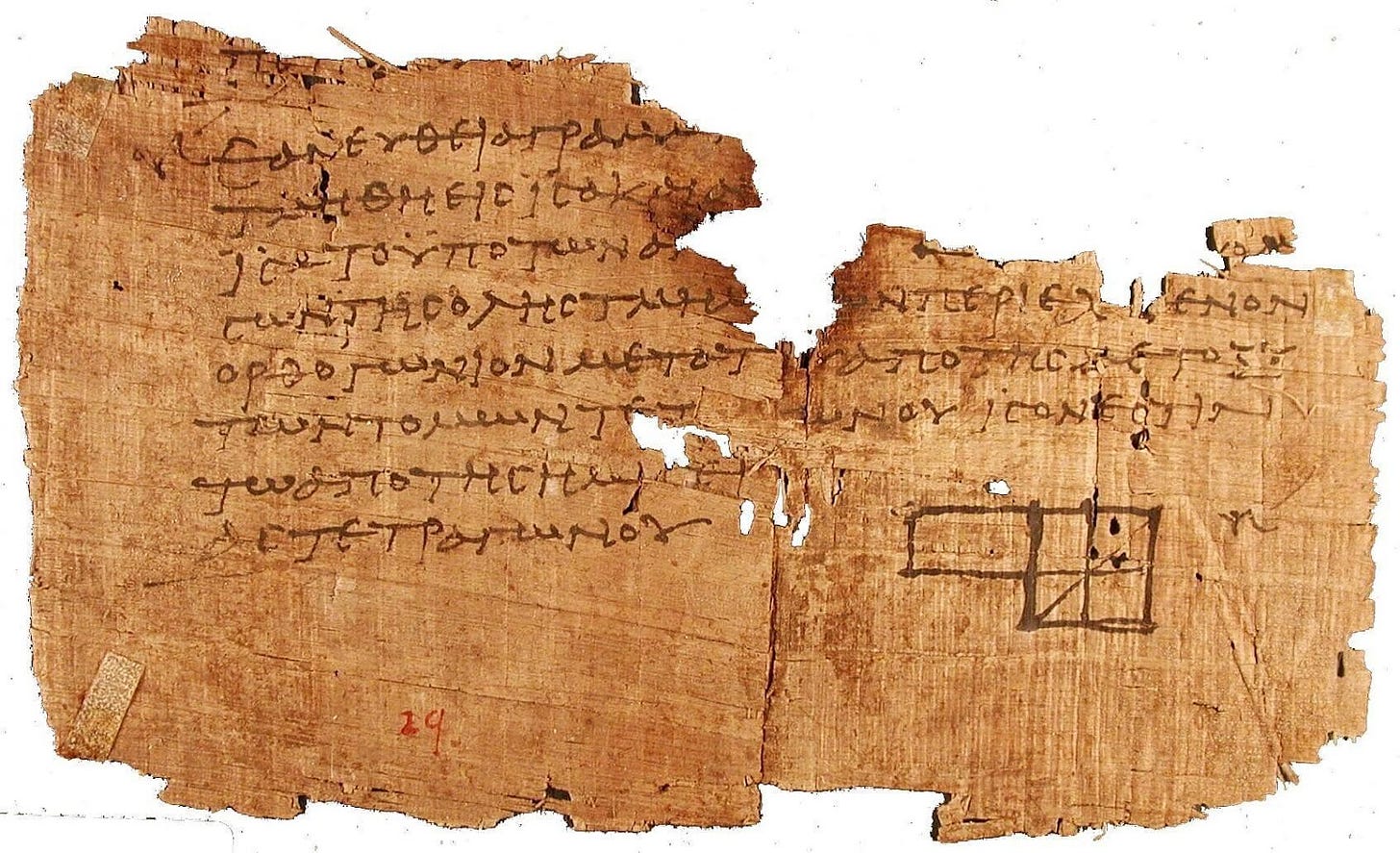

While scholars were sorting out chaotic threads of textual transmission, ancient papyri were discovered and another major stream of material entered the mix; one that had been cut off from any transmission thread for over 1,500 years.

Perhaps the oldest literary material found in Europe is the Derveni papyrus, which preserves a quote from Homer’s Iliad. The only reason for its unusual preservation is that scraps were found carbonized in a funeral pyre, which is similar to the many scrolls that were found in Herculaneum due to the eruption of Vesuvius.

The Derveni papyrus was created in the 4th century BC in Macedonia, the same region and time as Alexander the Great. As Plutarch allegedly wrote, Alexander the Great visited the Oracle at Delphi to receive a prophecy before launching his invasion of the known world. The empires created in the wake of Alexander are the reason for the Greek language’s high status in the Eastern Mediterranean and the foundation of the Library of Alexandria in the 3rd century BC.

For the first time, the Greeks weren’t contained to numerous small city-states organized by verbal debates in town squares, but ran a multi-continental and multicultural empire that needed massive amounts of intellectual capital and resources to run one of the world’s largest empires. The scholars at the Library amassed scrolls attempting to standardize the bewildering number of variations already apparent in the works of the ancient Greeks. To create the first editions of ancient Greek texts, they compared extant scrolls, debated their merits of authenticity, and produced texts with notes strewn across the page much as modern scholars do today in their efforts to precisely determine what the Greeks who came before them had said.

Centuries later, those Alexandrian editions were copied and some of the resulting post-Alexandrian scrolls were likely part of the transmission thread used for the even later Byzantine codices. Eventually, some scrolls were discarded in a dump in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt during the first few centuries AD. Under the sands, the millions of mostly tiny fragments were preserved simply due to the extremely low level of moisture and humidity in the area.

Most of these texts are administrative documents for the region, but about 10% are literary. The tiny fragments of ancient literature have been painstakingly edited and continue to yield new discoveries that add variations or verses to existing texts. Some texts, however, have their only extant evidence in these remains, such as a fragmentary copy of Aristotle’s Constitution of the Athenians. This text has survived not through continuous human intervention but survived primarily due to the environmental conditions of Egypt.

Media Materiality

The survival of texts based on the materiality of their media in certain environmental conditions rather than continuous human utility raises the question of the materiality of the media that the world possesses today which contain ancient Greek texts.

The oldest extant Greek literature was written on papyrus, initially as scrolls before being utilized in codex form. Papyrus was the main writing surface for millennia in the Eastern Mediterranean before parchment overtook it around the 5th century AD. During the period of parchment dominance, the orthographic shift from majuscule to miniscule script took place in the 9th century. Greek texts were slowly copied onto paper and became the dominant material after the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. The scrolls, manuscripts, and books could survive for centuries without being used as a model for a future copy, and indeed we still have quite a few of them with us in relatively good condition over a thousand years since their creation. In other words, the refresh cycle needed to maintain those texts was and remains relatively long.

Based on the ancient materials and the resulting centuries of transliterations and scholarly debates, there are now modern critical editions of Greek texts printed on paper in the thousands from collections such as the Oxford Classical Texts and the Bibliotheca Teubneriana. All the material in academic papers alone may be enough to reconstruct a relatively complete corpus of ancient Greek texts. However, unlike the old paper made from hemp and linen rags, the vast majority of paper in use since the 1800s is from lower-quality wood pulp. Wood pulp’s acidity and short cellulose chains make it liable to dissolve in a matter of decades.

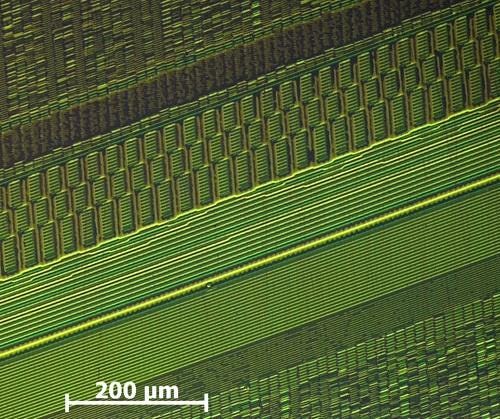

In addition to the transference of texts from one medium to another, there is inherent value in the very format of older textual materials like manuscripts, which sometimes preserve information that can’t simply be copied to a new format. Thus, there are facsimiles of specific manuscripts in digital formats like magnetic tape, floppy disks, optical drives, and hard drives. These resources are copied in the millions and their accessibility results in findings that would otherwise be impossible, including by amateurs like myself.

While creating a guide to understanding the layout of a Byzantine manuscript, I utilized the tools and images from The Homer Multitext Project, which is supported by Harvard University’s Center for Hellenic Studies. The Homer Multitext Project carefully photographed manuscripts that contained the Iliad and created digital copies to indirectly assist in the preservation of the manuscripts. The Project also built an impressive suite of tools that empowered users to search for and identify various categories of information in the manuscripts. While using these tools I found to my dismay that many features no longer work. Only one manuscript can still be searched within their software, and only in very limited ways. Many functions don’t work at all and bring the user to an error page. Unfortunately, even top scholars in the field of Classics with support from the wealthiest academic institution in the USA find it too cumbersome and expensive to maintain this kind of digital infrastructure.

Despite the huge number of ancient texts and their modern re-creations scattered throughout the world today, the future existence of ancient Greek texts is far from assured. Digital media is constantly at risk of decay and the infrastructure required to support each item is far more intense than what was required to support Greek texts at the Library of Alexandria or Christian monasteries.

My end-user experience doesn’t necessarily mean the digital storage of the images themselves is at risk. However, the creators of the project themselves hypothesized in their companion book to the Project that the high-end electronic devices holding the digital copies of the manuscripts, which were created in 2008, will likely not be operational in 2018, and that “only a miracle” would allow them to continue functioning by 2028.

Magnetic media is the technology used in hard drives and flash drives to store and transmit data. As a human can’t read directly off those drives, a technological intermediary like a computer is necessary to read the data. These storage units transfer hundreds of millions of bits per second in the forms of “1s” and “0s” to communicate their information. These 1s and 0s aren’t numbers of a screen, however, but the fundamental lowest unit of information structured in a binary relationship. The ‘bits’ are tiny, physical materials that momentarily exist along magnetic bands to be read by the computer which renders the information legible to a human reader, such as a Greek text. The problem is that without regular usage magnetic charges easily dissipate, and even through regular usage a hard drive will quickly decay.

Ultimately, when compared with previous centuries this circumstance of preservation and transmission is merely a difference in degree, not kind. Texts still need to be copied to a new material to preserve them. Furthermore, the timescale of this refresh cycle is mere decades with newer technology, rather than centuries with prior media. With the greater number of available texts in our possession, there is also a greater amount of intellectual labour and expertise required to maintain the infrastructure to support these refresh cycles.

There is one newer material that likely lasts longer: microfilm. Kodak, which introduced polyester-based microfilm in the 1990s, has claimed that in perfect conditions their microfilm can last up to 500 years. Besides the fact that this claim can’t yet be proven, it’s remarkable that even the most promising of modern media will almost certainly not last as long as the extant media from the printing press and before. Although 500 years is a long time, it pales in comparison to the grand life of the transmission of Greek texts.

It is spectacular to have discovered ancient papyri hidden for over a thousand years, but such fortune cannot be taken for granted. It’s extremely unlikely for texts to survive without providing continued utility to secure continual interest in them, the creation of new copies, and, therefore, their future transmission.

Ruins vs Literature

There is one material I haven’t yet discussed: stone. This essay began with a question of how Plutarch’s texts from nearly 2000 years ago can be read today despite none of his autograph copies surviving. Through his texts, we can begin to understand the operation of the Oracle at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. What about the site of Delphi itself; does it not reveal its histories, religiosities, and philosophies? There are copious archaeological remains from Delphi that help reveal aspects of its history, and the site itself is a major tourist attraction. However, that materiality is not the reason for its life in the imaginations and manuscripts of the thousands of years since the alleged historical and mythological prophecies of its Oracle.

Delphi contains more inscriptions than anywhere else in Greece, such as steles noting grand sums of donations to Delphi and inscriptions outlining the number of soldiers who died fighting against the Persians. These provide historiographical information about what occurred, when, and how that information, whether true or not, was displayed to the public. But they are not literature, they don’t explore societal debates or conflicts of the soul.

More importantly, for over a thousand years, Delphi essentially existed in literature only. When the oracle lost her powers over a world that had moved on from Greco-Roman religion, Delphi was abandoned. Buried under dirt over the centuries, a modern village had unknowingly been built right over the old ruins, which were discovered and excavated in the late 1800s. If it weren’t for the hundreds of prophecies that were allegedly uttered at Delphi, preserved and discussed over the millennia, would anyone have cared to move an entire village to excavate a pile of rocks? Would people’s imagination be fired up by a few stones of the Temple of Apollo, or is it not the place of Greece that essentially matters, but the place it occupies in the mind?

Case in point: The most famous inscriptions at Delphi such as “Know Thyself”, “Nothing in Excess”, and the mysterious “E” were never found in the excavations. They are instead known through texts like Plutarch’s that have been passed down the millennia. Indeed, Plutarch’s texts about Delphi aren’t historiographical information written for an unknown, future reader about what happened in Delphi; they’re a philosophical dialogue in the model of Plato between multiple people that ultimately explores the nature of the soul. That modern readers of Plutarch can glean historical information for their visit to Delphi through his text is simply a byproduct of the original intention of Plutarch’s texts, and clear evidence that the same text can be utilized differently by two utterly distant societies.

Utility, not Materiality

While some texts, like Aristotle’s Constitution of the Athenians, are preserved through environmental preservation, if ancient Greek literature wasn’t still in vogue and in use in the 1800s, would anyone have the care or funding to sort through millions of tiny pieces of papyrus in the middle of the desert? Would anyone even be able to read them and put them together? Environmental preservation and modern technology alone cannot be relied on to preserve ancient Greek texts. They can only continue to be preserved with ever-growing labour and interest.

Unlike the ancient literature preserved in the tombs of ancient Egypt, created for the private purpose of navigating the afterlife, the literature of ancient Greece has always been engaged with through dialogue, often in public. Many texts likely began in venues of exchange, like the Socratic Dialogues and dramas of the Tragedians.

The culture of knowledge production that generated Greek texts in ancient times has continued – re-imagined, reformed, reduced, and often misquoted – in the following millennia as people from vastly different stations and circumstances around the world continued to utilize whatever version of the texts they had at hand for their own inter-relational efforts in religion, statecraft, philosophy, education, science, and historiography. As Greek texts were engaged, their materiality was continually instantiated in slavish copies, paraphrase, translations, and critical editions. These renewed materials allowed Greek voices to continue reverberating and reflecting off the walls of time until heard once again as something fundamentally important, continuing the transmission anew.

Transmission, utility, and ingenuity have been the keys to the creation and subsequent survival of the selection of Greek texts that survive today, not the preservation of their materiality. Given the constant, irreversible decay of the materials that contain Greek texts, only if modern and future societies engage with Greek literature as items of utility will future millennia have a chance to hear the echoes of the words of the ancient Greeks.

For sources researched in the production of this essay, please refer to James Binks' bibliographic post here. It is continually updated with sources as new essays are written.