Watch a video version of this post here.

Santa Claus1: jolly, portly, bearded, and red-cloaked. He knows when you’re sleeping, and he knows when you’re awake, so that he can deliver gifts inside your home and escape unseen into the night sky. Bemused with his own break-and-enter — generous as it may be — when he finally steals away in his sleigh of flying reindeer he can’t help but cry with joy: “Ho Ho Ho! Merry Christmas!”

Did Santa Claus really say “Ho Ho Ho”?

Despite the efforts of countless mischievous children who have slept with one eye open in the hopes of catching the man in the act, there is still no evidence of Santa Claus. Unfortunately, it’s entirely possible that he doesn’t in fact exist, and therefore hasn’t said anything.

But what about the original ole’ Saint Nick? Did he say “Ho Ho Ho”?2

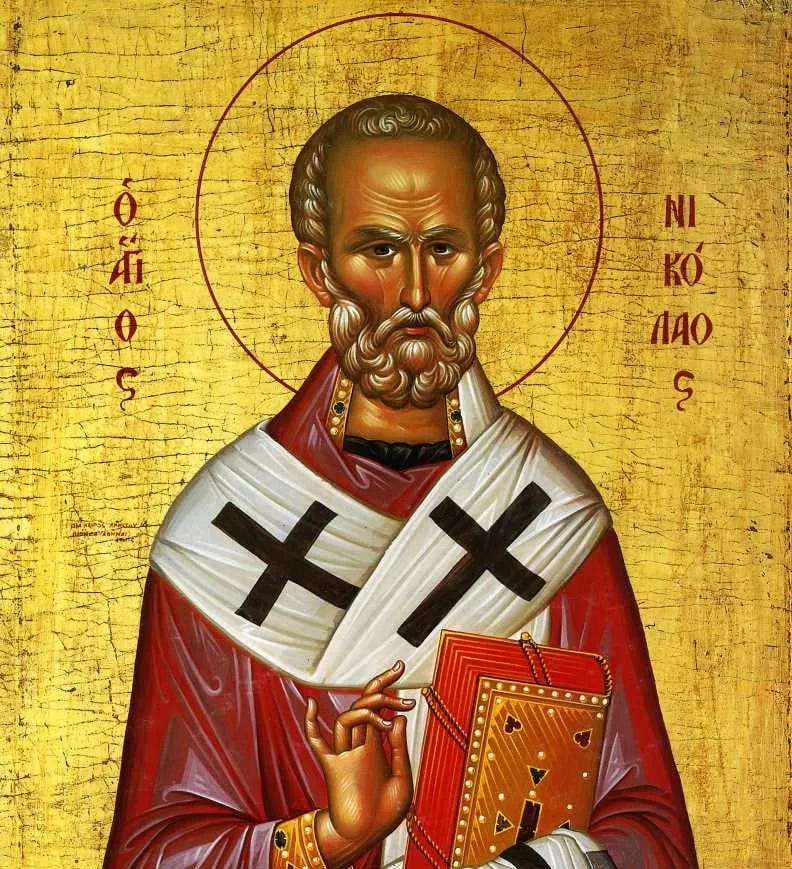

The 21st century incarnation of Santa Claus is distantly linked to a man named (Saint) Nicholas, who was a Greek from the region of Lycia and became a bishop of Myra (in modern day southern Turkey). Nicholas was born in the late 3rd century AD to Christian parents who died to an epidemic when he was young. His early life was consumed by persecutions against Christians, as dictated by the edicts of the Roman Emperor Diocletian. The Christian religion, with its one God, was at odds with the notion of sacrifice towards a polytheistic pantheon, and especially the Imperial Cult which worshipped the living emperor himself. As Christians faced and resisted this suffering, their resolve became legendary and strengthened their reputation. Many – like Nicholas – became martyrs and saints.

So, no, there is no evidence that Saint Nicholas laughed with pure joy like Santa Claus. Given the derision that early Christians faced and the laughter and humiliation Jesus faced during crucifixion, the major Church Fathers around Saint Nicholas’ time (Clement of Alexandria, Basil of Caesarea, and John Chrysostom) all viewed laughter in earthly life as negative and indicative of a lack of self-control. Laughter was for the Kingdom of Heaven.3

Alas, I searched the existing literature4 of direct accounts from Saint Nicholas’ life and words yet didn’t find an onomatopoeic representation of laughter, nor even a description of particular happiness from him.

However, there is a rather familiar story in the life of Saint Nicholas in which he did bring joy to others.

The Story of the Dowries

The story goes that a man fell on hard times and as a result couldn’t afford to provide dowries for his three daughters. Without a dowry (which is a transfer of money or property from a bride’s family to the new groom’s family), this man’s daughters couldn’t marry. With few chances at other employment, they faced a life of hardship, or even prostitution.

While he was just a young man, Nicholas (not yet a priest or bishop, let alone a Saint) heard of the family’s plight and — potentially with the money from his deceased parents — sneaked to their house under darkness of the night and tossed a small purse of gold coins through the window. The ecstatic father quickly arranged a marriage for his first daughter. Shortly after, Nicholas repeated his scheme so the second daughter could be married.

“[The father] was seized with joy, and with ungovernable tears gave thanks to God with amazement and astonishment.” – Life of Saint Nicholas of Myra, Michael the Archimandrite

Determined to discover who this gift-giver was, the father stayed awake in the hopes of hearing the delivery of a purse for his third daughter. Sure enough, Nicholas climbed to the window and dropped the dowry. The father jumped out of bed and raced outside, catching Nicholas as he tried to sneak away.

Nicholas didn’t want shame to come upon the family for accepting charity, nor did he have so much wealth that he could risk his deeds becoming public knowledge. Nicholas bound the father by oath to not tell a single person about these blessings for as long as the he lived.

…Clearly, the father broke his oath, or else I wouldn’t be recounting this story 1,700 years later.

How we ‘know’ what Saint Nicholas said

Other than the impoverished father making this story known centuries ago, how do we know this story?5

The life of Saint Nicholas is not well documented. As with most ancient Greek literature, we don’t have surviving material textual evidence from any of the parties involved in the alleged events, nor from the period in which they may have happened.

First of all, to verify the simple existence of an important man named Nicholas, we may turn to the attendance list of the Council of Nicaea, which took place during Saint Nicholas’ life in 325AD, and to which all 1,800 bishops across the Roman Empire were invited. Nicholas, Bishop of Myra, is included on some lists (but not all). However, he was not included on any of the lists until one written by Theodore the Reader almost 200 years after the Council of Nicaea, and in any case the earliest surviving manuscript which contains this inclusion is from the 12th or 13th century.

What about archaeological evidence? To this day there stands a church to Saint Nicholas in Myra (now called Demre) in Turkey, which has remains from as early as the 6th century, and was allegedly built on top of an even earlier church in which Nicholas would have served as bishop. It is here that the skeleton of Saint Nicholas was held, until in 1087 his bones were taken to the town of Bari in Italy, where they are still held in the Basilica di San Nicola. In the 1950s, the bones were taken out of the crypt for the first time in nearly 1000 years and examined, whereupon it was found that the bones were of a man at least 60 — or possibly 70 years old — with signs of physical stress such as a persecuted Christian of the 4th century may exhibit6. It is therefore likely that someone influential lived around the period of Saint Nicholas.

There is evidence of a cult forming around Saint Nicholas within one or two hundred years after his death, and his name and stories do appear in several texts and fragments composed over the 500 years following his death. For instance, the Praxis de Stratelatis (Deeds of the Commanders) is a story in which Saint Nicholas is said to have appeared in a dream of Emperor Constantine demanding that the emperor free three commanders who were unjustly sentenced to death. This story could have been composed around 400AD or as late as 580AD, but the earliest surviving material evidence of this story is a torn up page from the 9th century. The writing is a palimpsest, meaning that three hundred years after the story about Saint Nicholas was written, it was wiped off in order to make space for a copy of the Book of Daniel from the New Testament.

As far as I can tell, this page is the earliest surviving literary evidence of Saint Nicholas anywhere in the world today.

The rest of the surviving textual evidence of the life and miracles of Saint Nicholas are in manuscripts no older than the 10th century. These manuscripts include the story of Nicholas providing gifts in the night to the impoverished father and his three daughters, which is part of the Life of Saint Nicholas (written ‘originally’ by Michael the Archimandrite) that comprises the earliest complete collection of all the known episodes of Saint Nicholas’ life. Whether these existing manuscripts contain stories of Saint Nicholas that were originally composed during the Saint’s life, were created centuries later, or were even new stories from the 9th or 10th century will likely never be completely known.

What is known is that the cult of St. Nicholas grew substantially during the medieval period and his stories were translated into Latin and several vernacular European languages. With the shrine to Saint Nicholas transferred from Turkey to Italy his story spread rapidly through the travels of the Crusaders and exploded across both Western Europe and his original Eastern Mediterranean home region. By the 12th century, Saint Nicholas was appearing in Latin texts more frequently than any other holy person save for Jesus, Benedict, and Peter the Apostle.7

How the cult and worship of Saint Nicholas transformed into the modern conception of Santa Claus is a multi-threaded, long, indirect, and complicated story… for another time. For now, if you keep your ears trained on the nearest window or chimney you may just be able to verify the existence of a form of ole’ Saint Nick first hand, even if he’s not laughing with uncontrollable ecstasy.

Research Sources: The footnotes below were the main sources I used in this research, although I always draw on other research and resources which I describe here. If you are looking for more information you can always reach out to me directly or via comment.

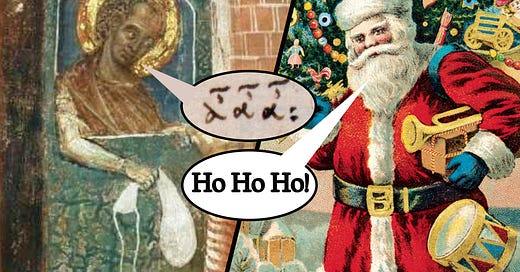

The essay’s initial image was edited by James Binks. Photo credit (left) Lateran Palace, Rome and (right) Cavallini & Co.

The “ἆ ἆ ἆ” in this essay’s initial image is taken from manuscript BML Plut. 32.2 (f.85r), which contains a line of onomatopoeic laughter by the character Silenus in Euripides’ play Cyclops.

Halliwell, Stephen. 2008. Greek Laughter: A Study of Cultural Psychology from Homer to Early Christianity, Cambridge University Press.

Summaries, translations, and more information about works on Saint Nicholas can be found at the St. Nicholas Center website, organized by the Virginia Theological Seminary (https://www.stnicholascenter.org/who-is-st-nicholas/stories-legends/classic-sources)

The most accessible scholarly resource and overview on Saint Nicholas’ textual transmission is: Blacker, Jean, et al. 2013. Wace, the hagiographical works : the Conception Nostre Dame and the Lives of St Margaret and St Nicholas, Koninklijke Brill. A less accessible but more complete (in German) resource is: Anrich, Gustav. 1913-1917. Hagios Nikolaos: Der heilige Nikolaos in der griechischen Kirche, 2 vols., Leipzig: B. G. Teubner (link).

See: https://www.stnicholascenter.org/who-is-st-nicholas/real-face/anatomical-examination

Philippart, Guy, and Michel Trigalet. 1998. ‘L’Hagiographie latine du XIe siècle dans la longue durée: données statistiques sur la production littéraire et sur l’édition médiévale’, in Latin Culture in the Eleventh Century: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Medieval Latin Studies, Cambridge, September 9–12, pp. 281–381.

Fascinating! I’d always wondered about this. 🙌🏼 Thanks for sharing!