A great parade, billions strong, heads to vote in democratic elections this year. If you have an eardrum or an eyeball then you’ve felt the debate and rancour of one polarized election or another.

Looking at the approval ratings of most leaders around the West, there’s a statistical likelihood that you, dear reader, are not pleased. And the alternatives? Chances are high you think they would be even worse.

You may find yourself asking why it is so hard to identify and elect that virtuous leader, an ideal character who would responsibly and intelligently wield power. And what can be done about those few corrupt politicians you’ve known in your lifetime who you wouldn’t trust as far as you can throw and who, despite clearly holding ill-intentions, remain incessantly buzzing and threatening to sting.

Allow me to make a proposal.

What if…?

What if… instead of voting for a candidate to take hold of the reigns of power, you could vote in a perfectly legal process to eject someone?

This person could be the richest, best connected, and most powerful individual. They don’t have to be a leader or even a politician, it could be anyone.

What if… when you vote to eject this person, they don’t just leave office or get fired; they must physically leave your community or country? They cannot participate in politics, rouse citizens, or meddle in your affairs.

You may now be thinking that this does technically exist. A tyrant can be arrested or put to trial. With enough force society could stage a coup or expel the leader through a bloody revolution. But that is politically, financially, and physically costly.

What if… there was no cost in this voting process? Indeed, there would be no trial, and therefore the expelled could muster no defense because there is no charge against them to defend. When voted out, this person simply must leave and that is the end of that.

But while the red-headed self-righteous knight inside you is licking their chops, there is a little voice on your shoulder warning you against this. It may not be fair. The ejection could be used to subvert due process and crumble the very values this process would purport to defend. The masses could be manipulated into a mad mob to a ruinous, brutal end.

What if… you could be assuaged with the fact that this person is not actually a criminal. They don’t lose their citizenship, get thrown in jail, and lose any official prestige or status. In fact, the family of the expelled may remain and any property they own is theirs to keep. After 10 years the exile can return and live as they like. They may even rejoin politics.

And isn’t that enough?

Imagine… All the angst, turmoil, and destruction wrought by a single person could be put out of mind. Is there a need for ruthless retribution if delivering justice will get in the way of the more pragmatic need to restore or ensure order in a well-functioning society?

Of course, other citizens remaining may continue in the ejected’s footsteps, but perhaps with the key figurehead gone a more moderate, manageable level of conflict could be maintained.

Is this a process that you would trust in your community?

Ostracism

For about a century in ancient Athens, citizens did have the ability to eject another citizen in a popular vote called ostrakophoria (ostracism). At the end of this essay I will muse on the origins and goals of this vote in society, but it is worth first asking how this process functioned, and how we know how about those functions.

Thankfully, ostracism is perhaps the most well documented ancient legal institution based on two sets of sources.

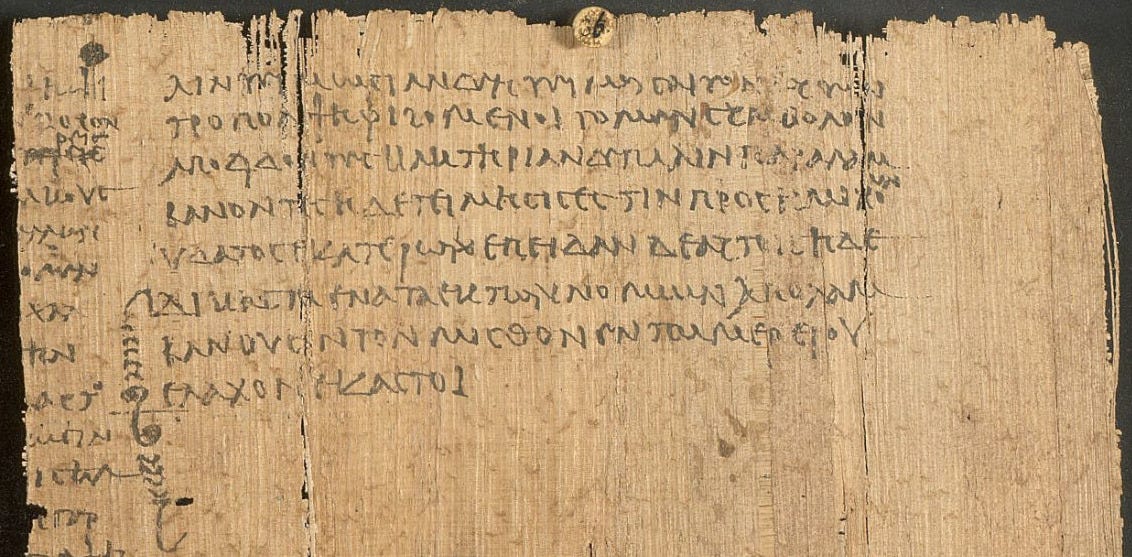

First of all, like much of ancient Greek history, there are copies of ancient Greek texts preserved in medieval manuscripts about the practice (such as historians Herodotus, Thucydides, and Plutarch). Remarkably, we even have a sole preserved ancient copy of Aristotle’s Constitution of Athens that was dug up from Egypt in the 1800s to supplement our knowledge. Although many of these figures composed their texts decades or centuries after the events they are describing, they are at least relatively well-attested.

But then we come to the most incredible source of knowledge: thousands of surviving ancient ballots that were written in the hands of voting ancient Greeks themselves.

The ballots are made of one of the most common materials in the ancient Mediterranean: broken shards of pottery. Clay pottery was locally produced, unlike papyri imported from Egypt upon which most long-form or administrative texts were written. Broken pieces of pottery were readily available, or easy to produce by breaking a low-quality pot.

A broken pottery shard with writing on it was (and is) called an ostrakon (plural: ostraka). This is where the term ostracism comes from (or ostrakismos in the Athenian tongue).1

Since these were homemade ballots, there was no single format. Generally the ballots would simply have the name of the person the voter is wishing to ostracize.

When the first ostraka were excavated in 1853 it was clear that these were ballots used for ostracism, because while ancient Athenians did vote in elections, in trials, and directly for/against policies, in those cases people voted by a show of hands or with pebbles placed into urns.

Once a year, citizens met and decided if they wished to ostracize someone. If they had a quorum of at least 6,000 voters present and agreed that someone would be ostracized, then an ejection campaign began and a couple of months later the vote would be held. Citizens could write any name on a pottery shard and submit it for counting on voting day (possibly the vote occurred in the Athenian agora).

Whoever received the most ballots was not elected, but ejected. They had 10 days to leave the city for 10 years. The ostracized individual wasn’t sanctioned, they retained their citizenship and their property, and after 10 years (or sometimes less) they could return. Many did return and several re-entered politics successfully.

More than 11,000 ancient Athenian ostraka have been discovered near where the voting likely took place and also in mass refuse dumps outside the old city walls. Remarkably, they mostly confirm (and supplement) our understanding of the institution previously developed based on ancient texts.

For example, the ancient texts say about 12 people were ostracized in Athens. They say that that in the 480s BC the citizens chose to ostracize an individual nearly every year, and then there were a smattering of ostracisms across the mid century, and the final ostracism occurred between 417 and 415BC. The types of pottery the writing is found on, the stratigraphic layer in which the shards were found, and the names on the ostraka (ballots) corroborate closely to the attestation from the surviving ancient texts.

The vast majority of the ostraka are clearly written in different hands. Thousands of citizens wrote these ballots, and they provide a snapshot in time like a time capsule. These ostraka are ancient texts attested directly from an ancient Athenian citizen and serve as witnesses into active historical events.

The Case of Cimon

The names on the ballots themselves verify history and tell us about literacy and linguistic development, but sometimes a voter wrote more than just a name.

When that happens, the page of history unfolds manifold.

In one incredible case, an ostrakon directly corroborates a story from an otherwise dubious textual source. Four speeches by an orator named Andocides (~440-390BC) were recorded long after his life. One of his speeches (Against Alcibiades) is of interest here because it provides information about several ostracisms that occurred, including an assertion that one citizen Cimon was ostracized due to an incestuous relationship he had with his sister Elpinike. However, scholarly consensus is that Andocides never did give this particular speech and that it somehow entered the textual tradition at a later date but was for whatever reason attributed to the orator.

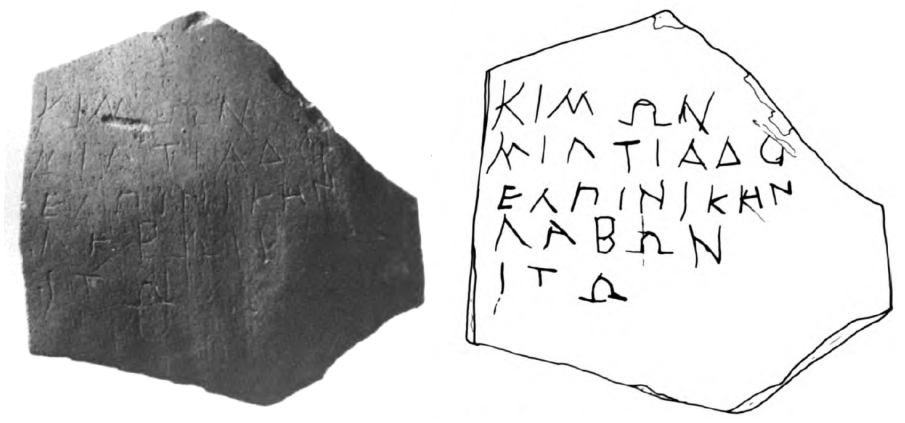

In the 1960s an ostrakon was discovered which not only names Cimon, but admonishes him by effectively stating:

“Cimon, leave and take Elpinike with you.”

ΚΙΜΩΝ ΜΙΛΤΙΑΔΟ ΕΛΠΙΝΙΚΗΝ ΛΑΒΩΝ ΙΤΩ

Does this prove that Cimon was ostracized for this reason? No, because other sources (such as Plutarch) state that he was ostracized due to a pro-Spartan stance. Does it prove that Andocides did in fact give the speech the texts purports him to have authored? No.

The key here is that whoever wrote “Andocides’” text, and for whatever reason Cimon was ostracized, we have evidence that a citizen in Cimon’s time and the author of historical texts decades (or centuries) later both independently believed that this type of transgression could warrant an ostracism.

By corroborating these sources we gain confidence in what both the texts and archaeology tell us about the functions and day-to-day actions of ostracism.

But what does this evidence say about the origins and purpose ostracism?

Equal Rights in Ancient Greece

Around 510BC, an Athenian leader named Cleisthenes ushered in a series of legal reforms. The changes that he made were guided by a principle of isonomia, the echoes of which reverberate continue to reverberate through the contemporary world.

“All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law.” - Article 7 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

Iso (fair or equal) and Nomos (law, norms, customs) was an ideal that laws should be applied equally to each citizen, and conversely that laws should be a fair expression of the real binding norms evident in society (rather than simply delivered by a select few elite ‘lawgivers’). Isonomia is most commonly translated simply as ‘equality’.

An isonomic society strives toward ensuring that there is no ruling class — no monarchs, oligarchs, aristocrats, or any individual — that act independently of the laws nor that retain the ability to create legislation without approval of the people.2

The ancient Athenians were not necessarily idealistic humanists that championed the cause of the individual, nor did they believe that all people were (or should be) equal in all things. They were less concerned with the rights of the individual than they were with the avoidance of tyranny, treason, violence, and disorder caused by corruption, excessive prestige or intra-elite conflict.

There were provisions in place to put someone on trial, to jail them, to have them put to death, to revoke their property and to permanently banish them. So why utilize a much more moderate punishment like ostracism which only temporarily sent them away?

Remember. As mythical as ancient Greece may seem, it was far from perfect and, after all, this is still the real world we are talking.

Let’s return again to our present frame of mind and consider our own misgivings and frustrations once more.

Do you believe that laws are always enforced equally or predictably? Does the legal process sometimes seem to take too long, cost too much, or be subject to corruption by people working within its institutions? Are laws outdated or lack coverage in a rapidly changing society? Are there people who are just too powerful that they feel, rightly or wrongly, that the law doesn’t apply to them?

Striving toward the principles of an isonomic society, the Athenians had no lawgiver, no monarchy, no special aristocratic few to resolve disputes caught in deadlock. If the faults in the machinations of their society threatened to propel them into the abyss of tyranny, only the people themselves could pull the lever of executive veto: ostracism. If the citizens needed a solution without delay, Athenians could choose to operate this extra-judicial release valve to address concerns of the citizens of the city.

When the historical record of Cimon’s ostracism is examined, we don’t know exactly why he was ostracized not because of a lack of records per se, but because the institution didn’t require a formal charge.

Some might have viewed his violation of social norms regarding his sister as too egregious to let slide. Others may have considered his foreign policies regarding the rival Spartans to be too disastrous to forgive. At the same time his aristocratic sympathies may have rung warning bells to the health of the experimental isonomic society always under threat in Athens.

In an isonomic society, nobody should be above the law. Safeguards against this were held not in a utopian bureaucratic legal system, but in Athenian trust in their fellow citizens. They allowed each other a method of (relatively) equal opportunity to enforce punishments by a popular vote to help prevent subversion, tyranny, and unproductive deadlock.

Would you implement ostracism?

Think back now to the persons conjured in your mind at the start of this essay, to the people whom you believe are a danger to the well-being of your society.

Would you be willing to give ostracism a chance to eject those who pose fundamental dangers?

By the end of the 5th century BC, even the Athenians had gained reason to pause.

In the midst of Athens’ Peloponnesian War with Sparta, two Athenian political rivals were in deadlock. Nicias wished to preserve a peace treaty he orchestrated while his rival, Alcibiades, advocated for aggression. A less-powerful politician, Hyperbolus, successfully led a quorum of citizens to agree to hold an ostrakophoria to resolve the issue by ejecting one of the two and in effect choosing which policy they preferred. Unexpectedly, the two rivals put aside their differences and campaigned to have Hyperbolus himself ostracized. Hyperbolus was then killed during his exile.

The last known ostracism appeared to have shaken the city’s faith in their neighbours to effectively render justice through the institution of ostracism.

When considering ostracism for the nascent United States of America, John Adams didn’t have much positive to say on the matter:

“History nowhere furnished so frank a confession of the people themselves of their own infirmities and unfitness for managing the executive branch of government, or an unbalanced share of the legislature, as this institution [Athenian ostracism].”3

Adams wasn’t alone. He was drawing on a whole retinue of ancient criticism of ostracism and of broader principles of elections and direct democracy writ large.

The question is whether ‘the people’ are wise, virtuous, or knowledgeable enough to effectively govern society. The ancient Athenians selected most of their officials by lot (sortition) rather than election to avoid popularity contests in which citizens are too easily swayed by the great deeds, prestige, or power of someone and elect them against their own best interests. Despite ostracism appearing to operate on the inverse, the same fundamental issues threaten its purpose.

In order for an institution like ostracism to thrive, there needs to be strong belief and trust in the judgement of the collective voice of the public.

The question is: Would you be willing to trust your fellow citizens to wield this power?

Sources

Ancient

(Pseudo-)Andocides. Against Alcibiades

Aristotle. Constitution of Athens

Herodotus. Histories

Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War

Plutarch. Parallel Lives (see esp. Alcibiades, Aristides, Cimon, Nicias, Themistocles)

Modern

Brenne, S. (1994). “Ostraka and the Process of Ostrakophoria,” in W.D.E. Coulson, O. Palagia, T.L. Shear, JR., H.A. Shapiro, andF.J. Frost, eds., The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under Democracy, 13-24. Oxford.

Brenne, S. (2002). ‘‘Teil II: Die Ostraka (487–ca. 416) als Testimonien,’’ in P. Siewert, S. Brenne, B. Eder, H. Heftner, and W. Scheidel, eds., Ostrakismos-Testimonien, vol. 1, Historia Einzelschriften 155, 36–166. Stuttgart.

Brenne, S. (2018). Die Ostraka vom Kerameikos. Kerameikos, 20. Wiesbaden.

Camp, J.M. (2001). The Archaeology of Athens. London.

Forsdyke, S. (2005). Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece. Princeton and Oxford.

Lang, M.L. (1990). Ostraka. Vol. 25 of The Athenian Agora. Princeton.

Ostwald, M. (1969). Nomos and the Beginnings of the Athenian Democracy. Oxford.

Ostwald, M. (1986). From Popular Sovereignty to the Sovereignty of Law: Law, Society and Politics in Fifth-Century Athens. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Roberts, J.T. (1994). “The Creation of a Legacy: A Manufactured Crisis in Eighteenth-Century Thought,” In J. P. Euben, J. R. Wallach, and J. Ober, eds., Athenian Political Thought and the Reconstruction of American Democracy, 81–102. Ithaca.

Wecowski, M. (2022). Athenian Ostracism and its Original Purpose: A Prisoner’s Dilemma. Oxford.

Ostraka are any potsherd that contains writing inscribed on its surface while it was a potsherd (not a piece of pottery whose writing dates to before the pottery’s destruction). In this essay, the word ‘ostraka’ is used more narrowly as only those which were used in the process of ostracism.

In the century before ostracism, more and more people were provided citizenship and expanded rights to participate in their society. Nevertheless, during the 400s BC neither Athenian women, slaves, nor foreigners could be citizens.

See Roberts 1994.

You leave out that Cimon was a hero of the war with Persia. Pericles had him banished because that is what phony intellectuals do against military men of stature. Cimon, Julius Caesar, Wallace, Patton ...