How do we know what the Ancient Greeks said?

I'm setting out to discover how stories have survived the millennia. (Transmission Pt. 1)

How do we know what the ancient Greeks – like the poet Homer, the historian Herodotus, and the philosopher Aristotle – actually said? Anybody who has been to Greece or watched a historical documentary hears historical tidbits like, “Pericles strengthened democracy in Athens” or “Leonidas won the battle of Thermopylae against the invading Persians”. On a recent visit to Egypt — where ancient, original text is preserved in tombs, temple walls, and on stunning papyri at archaeological sites and museums — I began to wonder ‘where are the original ancient Greek texts?’. How do we know who said what, when and where? How do we have complete texts of ancient Greek histories, societies, and science?

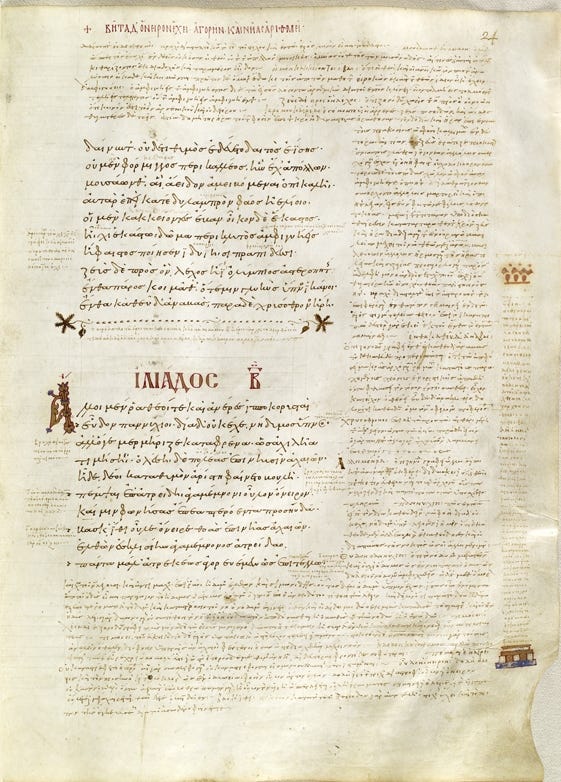

Well, the short answer is that we don’t have them. Not a single manuscript written by an author themselves or during their life from ancient Greece survives. Any manuscript we have, whether it’s Homer’s Odyssey or Euclid’s Elements, is a copy of a copy some number of removes from the original (if it even existed as the copies suggest they did). In fact before about a hundred years ago when ancient pieces of papyri were discovered buried under Egyptian sands, there had been scarcely any piece of Greek text that was written before Roman times at all. Even still, what has been discovered may be numerous but is extremely fragmentary. Therefore, the numerous influences of ancient Greece, from Greek figures in Raphael’s The School of Athens to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s A Defence of Poetry were instead passed down continuously since ancient times.

“… never at any other period has so much energy, beauty, and virtue, been developed; never was blind strength and stubborn form so disciplined and rendered subject to the will of man, or that will less repugnant to the dictates of the beautiful and the true, as during the century which preceded the death of Socrates. Of no other epoch in the history of our species have we records and fragments stamped so visibly with the image of the divinity in man.” - Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1821 celebrating the society of the Greek 5th century BC

How can people like Shelley feel so strongly in their conviction about what happened thousands of years before them? Sure, some Greek text inscriptions have survived among the various ruins around the rim of the Mediterranean, but these are far from the wealth of literature, science, and politics we all hear celebrating the Greeks and the world’s intellectual debt to them.

I decided to set out to discover what the oldest extant Greek texts are, how well and completely they are preserved, and how these texts and stories have been passed down to us well over two millennia in the future.

A Multi-Part Series

I had only an inkling of how complex this question would be when I cracked open the first book, peering in to an epic cycle of history which is itself worthy of the deeds of gods and heroes. You see, learning about ancient Greece isn’t like learning about the ancient Egyptians. The Greeks have never really been seen as a long-lost or overtly exotic civilization. Put simply, the effect the Greeks have had on history itself – its religion, literature, science, politics, and soul – has already required the tireless efforts of scholars since ancient times. Indeed, beyond engaging with the Greek works for their own brilliance, learning about how ancient Greek work was used by the world’s history-makers – from the mathematician al-Khwarizmi to the Catholic titan Thomas Aquinas to the American revolutionary Thomas Jefferson – is just as fascinating.

As I began my research about how texts were passed on after Ancient Greece, I was beginning to understand the material transfer of ideas forward through the millennia. And that’s just it: millenia. A massive measure of time spanning such change that I struggled to grasp why people continued to want to copy and engage with Greek texts anyway. I felt I needed to dwell a little longer on Ancient Greece itself before leaving it behind.

Sometimes it feels that through our movies and books and comics and classrooms that there is a very close and direct access to many inhabitants and ideas of Ancient Greece, when in reality it is heavily mediated by the inhabitants and ideas of the millennia that cleave between us. What the fine locals of the Byzantine, Abbasid, Renaissance, (etc.), time periods told me is that there was truly a ‘Greek world’, not merely a country or society. Despite differences in epoch, religion, or technology, people discovered profound usage in the works of the ancient Greeks.

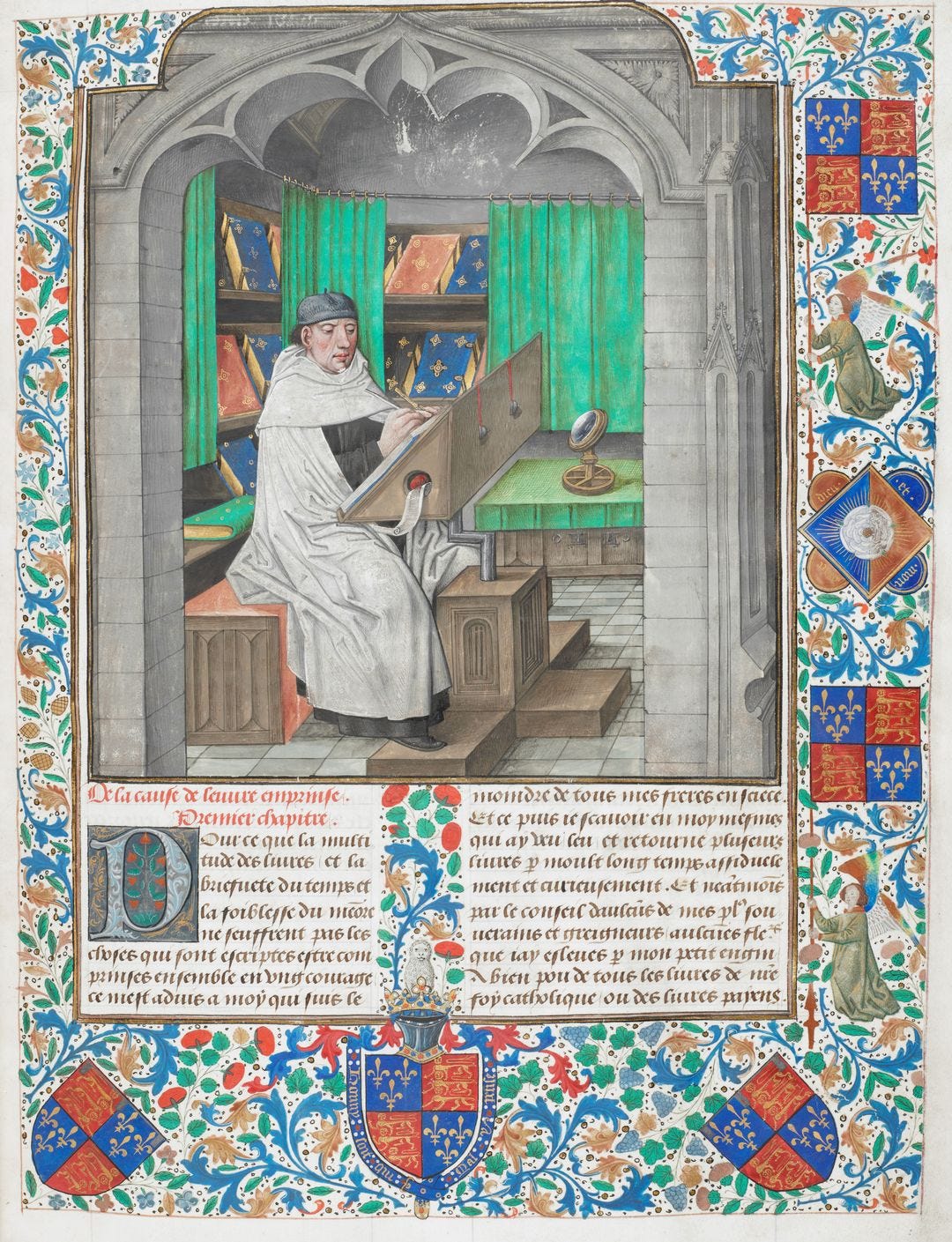

It may seem that I’m making a big deal out of nothing. 'So what? The Greeks wrote important and entertaining things and future people wanted to keep them’. But it needs to be appreciated that literacy and engagement with literature was entirely different in the past. First of all, to preserve a fragile, decaying material like a scroll or codex despite problems of fires, humidity, rain, conquest, general decay, misuse, and re-use of materials is difficult in any time period. Second, copying and producing a book wasn’t as easy as pressing Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V, and then Ctrl+P. It would take months and a massive investment of time and money in order to copy down, engage, illustrate, and bind a book in the days before the printing press. One needed to be truly entranced and well-organized in order to preserve a large piece of text.

In this post, I won’t be able to explore the transfer of texts forward through time, or go into detail about all of the contributions of the ancient Greeks. What I am seeking to do now is sketch out the definition of ancient Greece in order to better understand their general impact. In the upcoming entries in this series, I will get into the meat and potatoes of the process of transmitting text from antiquity until the invention of the printing press.

The vast span of time through which Greek texts traveled helps illustrate just how remarkable it is that we can know so much about ancient Greece… or can we? How much can we trust ancient sources? How much can we learn from an ancient text, the society it purports to talk about, and the people who wrote it? These are all topics that I intend to explore elsewhere in Culture Cross.

Conceptualising Ancient Greece

Before we can begin to explore how we (may) know what Ancient Greek individuals said, we need to consider what ‘Ancient Greece’ means. I’d like you to engage in a thought exercise. First, forget everything you know and have experienced with the modern country called Greece. Forget its size, its islands, and especially its particular location, shape, and boundaries in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. The modern Republic of Greece (Ελληνική Δημοκρατία, lit. Hellenic Republic) was founded in 1821 in a revolution against the Turkish-ruled Ottoman Empire which had controlled the Greek people for almost four hundred years. The revolution of the Greeks was supported and partially shaped with the hands of the British, French, and Russians. At the time, Athens had no more than 400 houses and some ruins. Cities like Constantinople and Smyrna, which today aren’t even in Greece, were far more important for the Greeks; not just in 1821, but for the prior thousand years and more.

Why is the metropolis of Athens the capital of Greece today? Allow me to return to one of my favourite points of comparison – Egypt. In 1798, Napoleon travelled to Egypt on his Egyptian campaign, kicking off Egyptomania for the world to begin rediscovering Ancient Egypt; not just its ruins but its whole history as a concept. On the other hand, Europeans had been engaging with Greek work for centuries. One of the most productive times in ancient Greek history was the 5th century BC. Athens and its playwrights, historians, philosophers, and politicians played a leading role in that century, about 22 centuries before the formation of the Greek state in 1821. Athens was still important for some time after the 5th century BC, but no city could be expected to reach those peaks again, as they didn’t in the Greek, the Roman, and especially the Byzantine nor the Ottoman periods. The supreme triumph of 5th century BC Athens was too tantalizing, and the other Europeans wanted to help re-create it. So they leapt over the 22 interceding centuries, stripped the city’s Parthenon of its mosque, Frankish tower, and other non-Classical structures, and installed a Bavarian Prince, Otto, as the King of Greece in the new capital city of Athens. A particular element of Greekness was being celebrated, and it is still a driving force behind the modern state of Greece, which in turn influences our perception of ancient Greece.

I can hear the angry Greeks in the background now. Have I forgotten about the Greek revolutionaries themselves? Of course not. The independence of Greece was primarily driven by a panopoly of hard-willed and intelligent Greeks, who were themselves inspired to unite with and draw upon their ancient predecessors. The horrific, unequal treatment they received at the hands of the Ottomans was the primary motivator for their freedom. Still, due to most Greeks living in the Ottoman Empire, and in general part of more eastern polities and influences for the entire period, the Ottoman Empire and the Greeks within it were not a part of most of the advances taking place in Western Europe, such as the Renaissance. Western Europeans had now been engaging with Ancient Greek thought in its original language for centuries, something that most Greeks weren’t able to do.

All kinds of outside interest manifested in modern Greece and coalesced into a revolution that likely would have been far, far more difficult (if not impossible) without the assistance of Britain, France, and Russia. As a result, Athens, not another more important city at the time, became the capital of the Greek republic we know of today. This rapid growth of Athens is why if you visit the city today, there is a stunning ancient precinct surrounding the Acropolis and its Parthenon, and just beyond that is mostly post-WW2 apartment blocks without the medieval or early modern buildings that make up other European capitals’ streetscapes (in fact, Athens did have several neighbourhoods built in the 1800s but which were bulldozed, but none from before that time).

Put in another way, while the modern environment of Greece may not always have perfect continuity with its past (such as Athens), the waves of history between ourselves and ancient Greece has still carried the intellectual and artistic history across the tides of change that have swept across continents, religious upheavals, societal transformations, and technological developments.

History of Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece was not a nation-state like the modern Republic of Greece and most other modern countries. Ancient Greece spanned a vast array of time and space: as tiny city-states, as empires, as democracies, as monarchies, as colonies and as many other experiments. Finding origins of something as nebulous as culture is subject to whatever categorization one decides on, but the generally accepted start of recognizably ‘Greek’ culture may be said to be around 1200BC with the Bronze Age Mycenaeans (centered in the city of Mycenae in the Peloponnese). The generally accepted definition for the end of ‘ancient’ Greece, which I will also use in this series, is around the end of ‘antiquity’ in the Mediterranean in general – about 500AD.

Its geographic location started more or less within the borders of the modern state, especially southern Greece (what I will call Inner Greece), but it quickly expanded well beyond them (what I will call Outer Greece). Greeks travelled the entire Mediterranean and Black seas founding cities and expanding their trade networks along the way. By the 4th century BC, Sicily (in modern Italy) and much of western Anatolia (in modern Turkey) were well-integrated with the ancient Greek world with Greek polis (city-states) of their own in the 4th century BC.

However, it is really with Alexander the Great’s conquering of millions of kilometres of land in Anatolia, the Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Central Asia, and parts of the Indus river valley in South Asia that ancient Greece expanded to its geographic apogee. Now, just because wars were raged, kings were installed, and political systems upended doesn’t immediately make a place Greece or people Greeks. But Greek forms of art spread, such as in the Indo-Greek kingdoms where naturalistic and stylistic representations of people from the Greek tradition developed and were applied to the Buddha himself in what may be the original anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha. Greek forms of knowledge systems were utilized, such as a list of Egyptian Pharoahs developed by Manetho for the Greek leader of Egypt which still forms the basis of our understanding of Egyptian leaders dating back to 3200BC. Even in Palestine when the Jewish prophet Jesus (who likely knew Greek, although his native language was Aramaic) was spreading his teachings at the start of our time reckoning system, Greek was the lingua franca of the entire eastern half of the Roman Empire.

Roman period of the Greek world

In fact, Inner Greece was not all that important in the Hellenistic period (which is the period after Alexander’s conquests until varying dates during the Roman Republic and Empire), when the centres of Greek civilization shifted to Greek founded cities like Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamum. Inner Greece was in fact conquered by the Romans in the 2nd century BC. However, as the Romans went on to conquer the other Greek-controlled empires further east, Greek culture continued to spread in transformed contexts. Aspects and locations of Greek culture were important for Roman religion and politics as Romans modelled much of their own culture after the Greeks. The lands of Inner Greece were important for pilgrimage (a kind of guidebook for pilgrims was written by Pausanias in the 1st century AD in his Description of Greece), and Greece had major centres of learning like Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum. In Outer Greece, Alexandria in Egypt with its library and lighthouse and wealth continued to be one of the most important cities in the Empire, behind only Rome itself.

Speaking of the importance of all things Greek in the Roman Empire, in future posts I aim to delve deeper into another aspect of Greek influence in the Roman Empire: Christianity. Christianity originated and developed within areas of the Roman Empire which had Greek as its lingua franca, and can be included broadly as part of Ancient Greece. Indeed, the New Testament itself was first written in Greek and by my own definition Ancient Greece (and antiquity) continued hundreds of years after the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

As a cultural and intellectual heartland, Inner Greece was visited by the Apostle Paul to spread the new Christian message in the 1st century AD. In Athens, Paul gave his Areopagus Sermon to defend and advocate for the worship of one God against the “ignorance” of polytheistic pagan worship. This is the exact same location and an eerily similar function as when Socrates – nearly 500 years prior – had been tried and convicted for his own prodding philosophical questions of the Greek polytheistic system. Other Greek regions and peoples were part of the development of Christianity as evident by the various Epistles sent to Greek cities such as Corinth, Thessaloniki, Ephesus, and Antioch. Therefore, Christianity could be described as a major component of Ancient Greece. Furthermore, there is a massive textual tradition to Christianity that goes along hand-in-hand with the textual transmission of other ancient Greek works, and as a field of scholarly inquiry is much more developed than the non-Christian texts. But this aspect of cultural transmission is simply too large and unique to include in the present series, so I will focus on non-Christian transmission of Greek works.

Now that I have mentioned language a few times, I need to expand on this. Language is the mode in which texts are conveyed across thousands of years. My aim in this series (particularly the second post) is to uncover how we know what ancient Greeks wrote about their science, logic, philosophy, myths, and literature. That is, through language. Not archaeological record in its monumental form of temples or numismatic evidence from coins or even inscriptions of a few lines of dedication on a statue. I am looking for full texts that discuss ideas or stories at length and in detail.

Although there is a modern language called Greek, there are some vast differences between it and its Ancient Greek predecessors. However, for a span of over 2,500 years it is not as dramatic as you may think. There have been several forms of dialects across space and social class in any one time, but in very general categories the main forms of written Greek are: ancient Greek (e.g. of works from Homer and the 5th century Athenians), Koine Greek (during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, including the language of the New Testament), Medieval or Byzantine Greek (the form of Greek after antiquity), and modern Greek (from the early modern period until today).

Just as many people today read the New Testament in its original Koine Greek to try and get closest to the meaning and source of the Words of Christ, the Apostles, and others, and students read Shakespeare in its Middle English – the oldest Greek texts remained in their ancient form, even in the later periods as the Greek language evolved. In fact, one element of preservation of Greek texts is that Greek was seen as an ideal, precise language which should be understood for its grammar even if not for its broader contextual meaning. In this way, the Greek language(s) in its forms aren’t necessarily tied to a particular period.

Mundane Exceptionality

To end, I want to now leave Ancient Greece in order to try and give a new view of the Greek world: from within. I studied anthropology in university, and a key tool for anthropologists in their work is to live with their ‘subjects’ (the people they are studying) for an extended period of time in order to come to understand how those subjects see their world. Even when an ordinary traveler goes to a new place, they will often be overwhelmed with the new sights and sounds until they gradually become more accustomed to them over their week-long holiday. You want to stop seeing the air, so to speak, and see the world as others do so that you can understand and empathize as they do.

In this spirit, I invite you again to a thought exercise to help suspend the layers of modern conceptions about the ancient past. Forget about philosophers in bland togas engaging in erudite conversation along columned-porticoes. Forget about masked performers singing odes to a god. Forget about nude athletes wearing olive-wreathes in their moment of triumph. Instead, think about a BBC news anchor breaking news about the death of Queen Elizabeth II. Think about The Lord of the Rings films filling theatres across the world. Think about the Super Bowl and your office conversations about it.

Let me explain.

Great Britain was once an island on the edge of significant historical developments, which rose to respectable continental prominence by the 15 and 1600s before rocketing to the centre of global power and influence in the 1800s (compare this to ‘Inner Greece’, e.g Athens, Sparta, Corinth developing up to its 5th century BC Golden Age). The countries Britain created or transformed sometimes went on to challenge or supercede its parent in power, size, and influence, yet these new lands were by no means just offshoots. From the USA to India to Australia, these countries under British government power had different people, different ideas about its history, and a different yearning for the future yet were inextricably linked to Britain (like the Outer Greek states of Ptolemaic Egypt, the Seleucid Empire, Pergamum, and in some respects even the Roman Empire).

Even as the Outer Greek lands prosper (USA et al.), the world of Inner Greece (Britain) continues to have importance culturally and historically. Think of the prestigious Attic dialect spoken at Plato’s Academy in Athens on the one hand, and the Received Pronunciation of English at the University of Oxford on the other. The study of Homer’s epics on the one hand and study of Shakespeare’s plays and King Arthur’s knights of the round table on the other. The political system of democracy on the one hand, and Westminster system of parliamentary government on the other. The Constitution of the Athenians on the one hand, and of the Magna Carta on the other.

Then the Outer Greek states, for which I’ll compare just to the USA for now. Libraries and intellectual institutions were founded in Pergamum and Alexandria, competing to be the most advanced centre of knowledge creation in the world, and American institutions continue to lead the technological revolutions which share information with the touch of a finger. These traditions of advancement led to one Eratosthenes calculating the circumference of a newly discovered spherically shaped Earth, whereas the Americans were able to voyage to the moon. In entertainment and art, theatres were built across the ancient Mediterranean entertaining tens of thousands, while American TV shows are constantly streamed to screens across the world. Perhaps no architectural feature is as famous as a fluted column from ancient Greece, and Americans pioneered the form of a fully inhabitable skyscraper.

Even people who advocate against British colonialism or seek to overthrow American economic control still live in a world pervaded by their co-creations and cannot fully avoid them as they go about their lives. And that is just the point of this exercise, to see ancient Greece as something mundane in its exceptionality. The forms these Hellenistic and Anglo cultural items carry throughout their worlds are immense. The form of the language, its idioms, its eccentricities, have carried those ideas and facilitated communication around the world. The cultural items are not necessarily discrete, categorized, nor marked as ‘Greek’ or ‘American’ when you live in a world constantly surrounded by them. They become essential, even if unnoticed. If not unnoticed, they are ripe to be co-opted. It is in this vein that the works of the ancient Greeks moved forward.

Onwards

I have discussed here that ancient Greece was a geographically and epoch spanning world that lasted for over 1,000 years. Yet that is not even half the length of the story of the Greeks. Greeks continued to innovate, persist, and migrate around the world. The Greek language’s importance in bureaucracy and religion thrived, and ancient Greek philosophy and science was used as a kindle for the explosion of cultural and technological shifts in Western Europe and the Middle East.

The next part of the story will be continued in the upcoming parts in this series. I will explore the actual transmission of texts from ancient Greece in its different forms to the invention of the printing press in the 15th century AD. How did the texts survive? Why did people continue to use and respect them, even as the world changed? An epic journey will be charted across continents and through religious change, persecution, linguistic development, political upheavals, technological regressions and advancements, and the decay of time.

To see which books and resources I used to research for this series on Ancient Greek Textual Transmission, please see here.