***Audio narrated version available***

I’m trying something new here, so please share your thoughts with me. One of my goals with my work is to create an accessible bridge between the events of history, and the dry or obscure academic works that can help us appreciate that ancient world. To that end, this is an ‘audio-first’ essay, where I first crafted this piece with the intention for it be listened to, and then touched up the script to make it more suitable for the eyes in its written format. Each version has their strengths. I hope this opens a new way to engage with my writing (thank you to aaronTmusic for supplying the wonderful backing music).

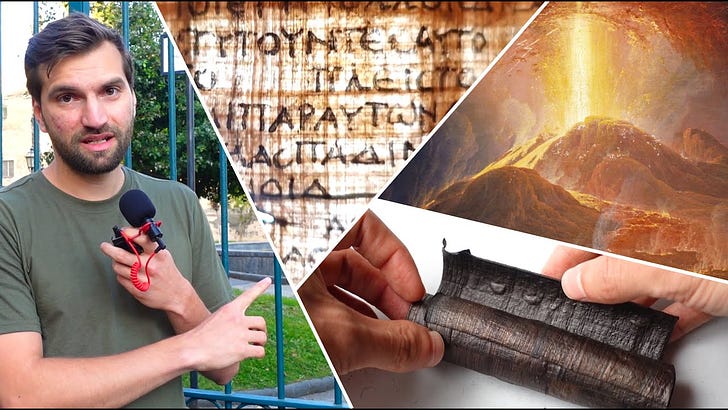

This essay gets close to both the origins of Greek literary transmission, and to myself, personally. From my own family to the origins of Greek and Latin writing itself.

Enjoy!

There’s an island in Greece you’ve probably never heard of.

It’s not Santorini with its volcanic crater and blue domes, and it’s not Mykonos, with its glitzy night clubs and Instagram worthy windmills. No, it’s much bigger than those islands. In fact, it’s the second largest island in Greece.

The island is called Evia.

The first reason I mention the island is because the people there, the Evians, invented something amazing. Something so useful I’m sure you use it everyday: to navigate the world, to earn your income, to entertain yourself.

The other reason I mention Evia is because, well… half of my family comes from this island. I remember the first time I went there. I was nine-years old. I remember the endless switchbacks through mountainous pine forests, the relief when the succulent watermelon hit my parched lips, the glorious sunsets giving way to a raucous family rendezvous under a calm, clear sky. In her later years, my yiayia, my grandmother, would regale anyone within earshot about how the first thing she did each morning was wake up, hike into the pastures, and milk 500 goats. That was all when she was just a nine-year old child, the same age I was on my first visit.

The island has always represented the ‘real’ Greece to me — raw and intimate. But there’s a reason it’s not on the tourist trail. There’s no Parthenon, no Olympic stadium, no whitewashed houses with blue shutters. It’s a beautiful island, but perhaps its people were left out of the classical achievements of ancient Greece.

Not so, as it turns out that without a group of people who called Evia home thousands of years ago (then known as Euboea), you might not have navigated your way to this post or be reading this at all. It is in no small part thanks to the daring seaworthy adventures of ancient Evians (Euboeans) that we have that most important tool of civilization: the ALPHABET.

But even though the Evians were Greeks, it’s not really thanks to them that we have the Greek alphabet, but rather the Latin alphabet.

The Evian encounter with the Phoenician alphabet

Of course, it wasn’t my family who invented the alphabet, it might not have even been my ancestors. You see, the Greek people have always been on the move. Just like my grandparents moved from Evia to Canada, there is a huge diaspora of Greeks around the world in cities like New York, London, and Melbourne. This settling of far-flung lands has its origins in ancient Greece.

Like the great energy of the seas, the Greek people have been splashing in waves of migration against the shores of the Mediterranean and beyond for thousands of years. Generation after generation set out on foot and by oar, to the next island, the next promontory, the next fertile plain. Sometimes they sought new land to grow, sometimes they escaped famine, plague, and war, and sometimes they just needed more materials — namely metals like iron, copper, and tin — for their tools, weapons, and armor.

In 800BC, the Evians went even farther than their neighbouring Greeks. They had seen that it wasn’t just the Greeks sailing the waters, there was another group of people they called the Phoenicians who were gliding straight through the Greek seas on their trading expeditions journeys to the far, far west. As far as the coasts of Spain and even Morocco. The Phoenician ships were sleeker, their clothes finer, their bellies fuller. Perhaps learning something from the epic journeys of the Phoenicians, the Evians didn’t do the Greek thing. They didn’t go to the next available spot. They leapfrogged bays, islands, and peninsulas. This led them right to the Levant, in modern day Syria. This is where they set up their trading post, Al-Mina, the first and furthest east of the Greeks at that time.

Evia has some of the earliest evidence of iron metal working in Greece, and so these early explorers were after metals, like iron, to support their growing economy back home. To the north and east of the Levant were abundant metal resources and the trade routes to secure them. But the Levant and the far eastern Mediterranean weren’t just host to resources, there were rich and ancient cultures too, including the Phoenician heartland, which lay just to the south of the trading post.

The Evians likely had few items of value to offer the highly organized and advanced cultures of this region, and they would find little space to settle permanently. The Evians would maintain a minor presence in the region, but they needed to secure metals and land in a more favourable region, one in which perhaps they had the technological and culture advantage. They soon turned their attention elsewhere.

But before they left, there was something they would take with them, something which would change the course of history.

They noticed the Phoenicians etching lines and shapes on scrolls, tablets, and pots. With this tool, they didn’t need to rely on the memory of a single person: What goods came in on the ship? What was the quantity? To whom is it for? What is the price? Instead, this information could be inscribed, a physical mark of the mind, shareable and transmittable to anyone who understands the code. But the code wasn’t based on an abstraction of the shape or quality of the item it describes.

No, the key to the symbols was sound.

Journey to Pithekoussai and Italy

With this new intellectual tool firmly in their tool-belt, the next generation of Evians set out on another long-haul journey. The year was 753BC, just 23 years after the first Olympic Games were held.

About a hundred men entered their station on a bireme, a boat with two rows of oars, and navigated past Athens, the isthmus of Corinth, the entirety of the Peloponnesian peninsula, until they were west of all existing Greek cities and territory. From here they crossed the Ionian Sea, winding their way past the heel and then the toe of the Italian peninsula. In the coming decades these coasts would be settled by other Greeks following in the Evians’ wake. Those trading posts and settlements would become powerful city-states in their own right like Syracuse, Croton, and Catania, who would rival the Greek homeland. Clearly, the Evians passed many suitable bays and offshore islands at which they could disembark and set up camp, but their lust for exploration was rivaled only by those Phoenicians, from whom they learned to continue until the furthest, suitable extremity.

As they pushed on, they began to enter the realm of myth. A land where, in the distant, impossible past — the age of Heroes — the cunning Odysseus wandered for year after year after year. Like Odysseus, the Evians threaded their ship between the narrow channel of water that separates the Italian peninsula from the island of Sicily, between the monster Scylla and its rocky cliffs on the one side, and the beast Charybdis and its treacherous whirlpools on the other. The Evians, driven by the keeper of the winds, Aeolus, came upon his own islands as they continued to push through to the north.

Eventually they came upon on a small volcanic island sitting like a jewel within striking distance of the Italian mainland and its deposits of iron and copper. They called the island Pithekoussai, but today the island is known as Ischia. It sits about an hour ferry ride away from the bustling metropolis of Naples.

It was undoubtedly a difficult life. They had rowed well over a thousand miles with little space on their craft for food and supplies, so they needed to make due along the way. And now that they reached Pithekoussai, their work was cut out for them to eke out a living in this foreign land and to return home with useful materials.

The Evians built their trading post in a defensive northwest part of the island, with a high promontory for their acropolis, a favourable harbor for trade, and lush volcanic valleys for food production. They built a furnace to smelt iron and craft the tools they would need.

But after such a long journey, they also needed a social outlet. It was likely only men from Evia that came on the journey, but for now, that didn’t matter much. All they needed were a few walls, a couch to recline on, and wine to consume in order to create a symposium (essentially an ancient party). A large mixing vase was filled with wine and diluted with water. From there, the wine would be transferred to at least three pitchers, but possibly many more. From the pitcher the wine would be poured into cups as needed throughout the night. And now, with this context, we can finally focus on the star of the show, a cup.

Yes, a cup, to drink with.

Nestor’s Cup and an ancient party

In the 1950s, archaeologists discovered an ancient cemetery, inside of which was an ancient drinking cup made of clay. To modern eyes it would look more like a wide, tall bowl, 10cm tall, 15cm in diameter, with two small handles protruding from the rim. Illustrating the cup are two bands, the bottom of the two being simple zig-zagging lines, and the top having diamonds, trees, and meanders.

The cup itself is simple, and not any more special than other ancient cups… except for one spectacularly unique feature – the oldest writing in a Greek alphabet, in the world1.

By now, Evians had become quite comfortable with their system of writing. It had been in use for decades and decades, if not longer. The Evians had adapted the Phoenician model of writing to fit their own language and its unique sounds. Some letters they could keep the same as they found them, while other letters had to take on a new sound, and other letters had to be entirely invented by themselves.

More importantly than the letters, the Greeks, wily are they are, expanded the very function of the writing. Sure, record-keeping of goods is important, but this is the age of Homer we’re talking about, of epic story-telling and philosophical exaltations. If goods have their written records, why not gods, heroes, and men?

So, back at a symposium on the island of Pithekoussai. Shortly after its settlement, there may have been a man named Nestor. Why? Because the first words written on the cup say “ΝΕƧΤΟΡΟƧ ΕΙΜΙ -- I am the cup of Nestor”. As you can imagine, a party with dozens of participants, copious amounts of wine, and a gregarious culture of sharing, may end up with a cup getting passed from Nestor, to Inos, to Nikos, and so on. Nestor might never see his cup again.

But the cup wasn’t necessarily labelled in such a possessive manner. On the cup, perhaps written by Nestor and his friends, are three lines of text, in poetic meter, which might refer to epic stories from Homer, which might compose some type of magic, or constitute a curse. Perhaps all three at once.

Here’s what it says:

1: Νεστορος - ειμι – ευποτον – ποτεριον

1 (ENG): I am the cup of Nestor – good for drinking

2: Ηος δαν ποδε πιεσι – ποτεριο – αυτικα κενον

2 (ENG): Whoever drinks from this cup, desire for beautifully

3: Ηιμερος ηαιρεσει – καλλιστεφανο – Αφροδιτες

3 (ENG): crowned Aphrodite will seize him instantly.

As the cup was passed around, consumed from, and read, the Evians might have taken it in different ways.

This could be a reference not to a person on Pithekoussai named Nestor, but the mythological Nestor, who had his own famous cup in the epics of Homer, alongside the likes of Odysseus. Perhaps the text is a nod to their shared culture.

This text could be linked in some way to a kind of love magic, in which the drinking of the wine and the incantation on the cup would lead to a pleasurable connection.

The text could also be a subverted curse. Based on literary conventions of the time, the first two lines suggest the drinker from the cup will be faced with a terrible curse, yet the third line changes course and upends the curse by leading to divine pleasure. It has been suggested that this subversion of the message suggests an advanced literary sensibility2. On the other hand, I don’t see why it couldn’t be a curse through-and-through… as I mentioned, the men likely travelled to the island without women, and yet from drinking the wine out of Nestor’s Cup, they are overtaken by feelings of intense pleasure. Without women, did they have somewhere to direct these feelings? Maybe, knowing the ancient Greeks, they could make it work (take that for what you will).

The creation of the Latin alphabet

In any case, reading love poems and drinking wine isn’t the reason the Evians made the difficult journey to this distant island. From their high town, the acropolis, on the top of a promontory, they could look out at the Italian coastline, stretching to the north as far as the eye could see. In central Italy were great deposits of iron and copper. But they weren’t just there to take, they also brought their pots, their oils, and their new alphabet.

The leading people in Italy at the time were a group of people called Etruscans. As they traded, the Evians found themselves in the favourable position now of being the technologically advanced people using the system of etches and symbols to record, preserve, and share information. The Etruscans, like the Evians had been in the Levant in past generations, were amazed at the tool of memory transference and speech emulation known as writing. As such, they borrowed the alphabet and in turn adapted it for their own language.

Just three years after the Evians settled at Pithekoussai, the city of Rome was founded. The Romans were at first neighbours to the Etruscans, and then became dominated by them, and the Romans soon came to absorb and adapt the alphabet from both the Etruscans and the Evians and Greeks (who were just 100 miles to the south of Rome). This exchange between one group of Greeks, the Evians, through their trade with the Etruscans and the Romans, led to the Latin alphabet.

Today, the Latin alphabet is today used in dozens of languages from English to Swahili to Vietnamese, it’s sound system is basically understood by almost any literate person regardless of origin, and this alphabet forms the basis through which we express ourselves through computing technology, and through which computers interact with each other.

Remnants of Evian writing in the Latin alphabet

From the three lines which are written on Nestor’s Cup, there are fifteen unique letter symbols. Despite this being an archaic version of a Greek alphabet, you can certainly read at least 7 of those letters (N, E, T, O, I, K, L). They would have been pronounced more or less the same as you would pronounce them right now. But there are many more letters from other cups and inscriptions in the Evian Greek alphabet which you would know too, like “C” and “Q”.

Interestingly enough, some of these letters which are in the Latin alphabet are not in the modern Greek alphabet.

It’s one of those glorious twists of tragedy and fate, endemic throughout the ancient Greek world. If one of those ancient Evians at Pithekoussai were to travel to modern Greece and read modern signs, they might feel like you looking at Nestor’s Cup. They would recognize many of the letters, but there would be others they don’t understand.

For example, the Evians had the letter “S” in their alphabet (sometimes written backwards, i.e. “Ƨ”)3, and introduced it to the Etruscans and Romans, which is where we get the letter “S” in the Latin alphabet. If you were to see the word “Nestor” as it’s written on Nestor’s Cup (ΝΕƧΤΟΡΟƧ), you would easily recognize the “S” from the writing, even though it’s nearly 3,000 years old. Yet if the Evian who inscribed that word on the cup time-travelled to modern Greece and read the name ‘Nestor’ in modern Greek (ΝΕΣΤΟΡΟΣ), he wouldn’t quite understand it. The modern Greek “S” (i.e. “Σ” - Sigma), looks different in the modern Greek alphabet.

Here’s what happened. Remember when I said that Evia isn’t exactly the most well known island?

Well, not long after settling in Pithekoussai, in the late 700s BC, the growing prowess and might of Evia from their powerful iron and steel weapons began to cause problems. The jostling of wealth and prestige caused fighting and jealousy amongst rival cities of the island (Chalcis and Eretria). Their conflict erupted and engulfed most of Greece in a conflict called the Lelantine War.

The war obliterated the cities of Evia, and they never properly recovered. The torch of Greek civilization began to be carried by other cities; cities which today are most often evoked in the name of the ancient Greeks, like Sparta, Corinth, and Athens. Case in point, in 402BC, Athens standardized the Greek alphabet into the 24 letters. Because of Athens’ power and influence at the time, those 24 letters continue to survive as essentially THE Greek alphabet. But that alphabet was based off of their own alphabet developed for their own dialect of Greece, the Athenian sound system, not the Evian one.

The Evian Greek alphabet, a bit like the island of Evia itself, has therefore been pushed to the margins. Nevertheless, we can witness that the island and its alphabet, endure. From the families and forests of Evia itself, to the writings left behind on an ancient cup and the celestial reach of the writing system we all learn as we grow up.

FURTHER READING

Boardman, John. 1999. The Greeks Overseas: Their Early Colonies and Trade, 4th ed. Thames and Hudson.

Faraone, Christopher. 2001. Ancient Greek Love Magic. Harvard University Press.

Jeffrey, L.H. 1990. The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece: A Study of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and Its Development from the Eighth to the Fifth Centuries B.C., revised edition. Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology.

Wachter, Rudolf. 2001. Non-Attic Greek Vase Inscriptions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wecowski, Marek. 2014. The Rise of the Greek Aristocratic Banquet. Oxford University Press.

There is another inscription in the Evian/Euboean alphabet which is about the same age. It is called the Diplyon Inscription and is held at the National Archaeological Museum of Greece in Athens.

See Wecowski (2014) and Faraone (2001).

The inscription on Nestor’s Cup is actually written ‘backwards’ (right-to-left), although other Evian writing is left-to-right or even boustrophedon, where the writing alternates direction by line. I have mirrored the text in this post so it all appears ‘normal’ (left-to-right) because the direction of the writing is not relevant here. However, the letter “S” is written left-to-right on Nestor’s Cup (just as in modern Latin alphabets), so to stay consistent I am here presenting it mirrored as well.

Share this post