In 1511, 28 year-old Raphael was putting the last touches on a fresco in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. Shuffling in slowly behind him was his patron, the elderly Pope Julius II, here to gaze at the masterpiece. The Pope knew his time on Earth was limited, yet his thin lips crested into a satisfied smile.

He would leave this realm long before Raphael could complete all the palace’s commissioned frescoes, but staring at this fresco with its two central figures suspended in perfect animation at the piece’s vanishing point, the Pope knew he had been right to entrust this task to the young Raphael.

The fresco in question is commonly called “The School of Athens”. It is a wall-sized fresco that contains a depiction of Plato reproduced across the world more than any other image of the philosopher. But this ‘Plato’ isn’t based on the likeness of Plato himself: Raphael’s depiction of Plato is drawn from the painter’s own contemporary; the aging polymath Leonardo da Vinci.

Nevertheless, Raphael’s ‘Da Vinci-Plato’ is the corporeal form of the great philosopher embedded in our cultural subconscious.

The true appearance of Plato is not so easy to recall.

Scarce information remains of the visual appearance of most ancient Greeks. This is true even for Plato, despite his literary corpora being arguably the best preserved of the ancient Greeks. Plato left behind an enduring legacy, but an iconographic tradition did not grow out of that legacy. There’s no rubric for the representation of him.

Trident? Poseidon. Dragon? St. George. Yet for Plato there is no standard symbol or attribute by which we can easily say with confidence, ‘aha! That is Plato’.

For instance, let’s look at busts. Search “Plato” on any search engine or encyclopedia and at first blush you will be presented with a sculpted face underwritten with a caption stating authoritatively: ‘HERE BE PLATO’. Dig deeper and you find a long series of scholarly battles waged with vast networks of inferences and tenuous connections based on incomplete historical data.

In 2003, Berkeley classicist Stephen Miller gave a second-look at a long-dismissed “forgery” of Plato. By 2009, the professor had marshaled enough arguments to pen a book arguing that this bust was indeed a true, ancient bust of Plato. The fact that an entire book is needed for this purpose and the theory is still not unanimously accepted encapsulates the complexity of identification.

We don’t really know what Plato looked like, or even how people in the past represented Plato.

Why does the appearance of an ancient philosopher matter anyway?

After all, it is from Plato’s mind and words that we still speak of him thousands of years later. While Plato’s exact appearance isn’t instrinsically important, the context within which his or any other ancient Greek’s appearance is presented to the public shapes our understanding of all the centuries leading back to ancient Greece.

When we see an image confidently labeled as an ancient Greek person in the news, or encyclopedias, or non-fiction books, or in a museum; what are we to do but defer to their authoritative voice? The issue is that identification of historical figures in artworks is rarely simple. When the identity is presented with a tone of finality, it belies the countless human creations and interactions over thousands of years that have gifted us the materials that help us discover history, and maybe — just maybe — to know it.

It is precisely the chain of human endeavour, ingenuity, and necessity across centuries that links us to the past. Without mention of those interceding centuries, history risks being just a series of remote and wacky anecdotes. But with acknowledgment of the winding and incomplete chain, history becomes a cultural process we too can inhabit; one that interweaves us in a link with those who came before us and those who will follow. Connection begets identity begets meaning.

I have been reflecting on historical attribution after a visit to one of the world’s great treasure troves: The National Archaeological Museum of Naples. Last month I wrote about how the experience of seeing room after room of diverse ancient art in the museum gave an eerie sense that the past is simply known.

This is not a criticism of Naples’ museum. It’s not the museum’s fault they possesss the most unique collection of art from ancient Rome in the world. They aren’t going to have empty spots on their walls to signify all the information we don’t know, nor would it make sense for tourists to endure thousands of pages of reference material around an object when they just want a basic sense of what they’re looking at.

With my modest platform here, my goal is simply to explore how we know what we (think we) know. That’s why to end this essay I will explore one of these ancient pieces of art, which the museum has titled “Plato’s Academy”, and outline the main arguments for why some scholars believe that Plato is one of the individuals depicted there.

Detectives of the Mosaic of Plato’s Academy (MANN #124545)

Mosaic emblem in opus vermiculatum made from polychrome tesserae. The mosaic depicts a group of philosophers, identifiable from their clothes and the symbols of their science, who are deep in discussion beneath a tree, between a votive column and a sacred gate with vases. In the distance there is a walled city. The scene is surrounded by a festoon of leaves and fruits, adorned with ribbons and comic masks. — Pompeii, Villa of T. Siminius Stephanus, outside a city gate (Porta del Vesuvio) [Museum’s Description]

Despite the title of the mosaic stating that this is Plato's Academy, the artifact label does a good job of describing the scene in the mosaic without overstating confidence in knowing who exactly is depicted here. It is a “group of philosophers”, so it could be Plato and related philosophers, or, as the next most supported theory says, the Seven Sages meeting in either Athens, Corinth, or Delphi. Some believe this image depicts Aristotle and other philosophers in his Athenian school: the Lyceum.

Across these theories, there are over twenty historical figures named as possible candidates in this mosaic. However, here I will simply show the evidence and rationale behind the argument that the 3rd figure from the left is Plato. Not because this is necessarily the strongest argument, but just as an exercise to explore the avenues taken to reach an identification of a figure in ancient art with a particular historical figure.

One important point to mention before going any further is that all the different arguments and theories regarding this mosaic have one thing in common: their primary line of argumentation is drawn from ancient textual sources. Comparisons to other artwork is secondary.1

Let’s start with the face.

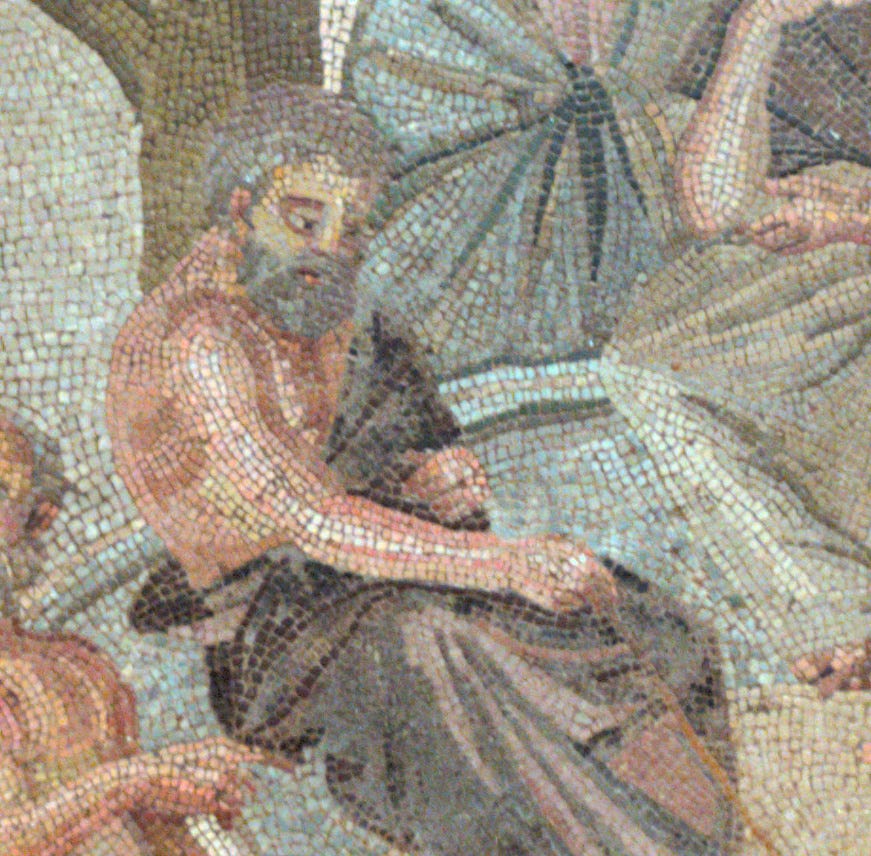

Here we can see the incredible craftsmanship of the mosaicist. With dark, downturned, and bagged eyes, this appears to be an old man, growing tired in his years. Can this collection of stones tell us this is definitively Plato?

In text, there are two direct references to the physical appearance of Plato's head. The first is from Simplicius, who lived nearly a thousand years after Plato, but wrote that he had beautiful eyes (or good vision) and a finely shaped nose (On Physics 4.14). But here Plato's pupils are a single cube (tessera). It's hard to depict beautiful eyes or great vision with that limitation.

The second reference comes from a description of Plato having a 'broad forehead' (see Laërtius Lives III; also referenced by Philodemus in Herculaneum papyri 1021). I’ll delve into this later, but for now we can see that the forehead on this figure isn't particularly broad or larger than any others in the mosaic.

In sum: we cannot identify Plato solely from this section of the mosaic.

Let's zoom out and look at the body as a whole.

The priest and historian Plutarch (who lived some 400 years after Plato) referred to Plato's posture in a section of text discussing the difference between true friendship and cheap imitation or flattery. It might be uncommon today, but allegedly in ancient times philosophers were imitated. Plutarch wrote that flatterers would copy all aspects of a person in an attempt to feign friendship, even their vices, and for Plato's admirers this meant walking around with a “stoop” (Plutarch Moralia I). This figure does seem to be in a posture with hunched shoulders, but that evidence is not enough to definitively state that this is Plato.

The museum's description of this mosaic gives us the most important hint, that the philosophers can be identified from "the symbols of their science". Although Plato doesn’t have an iconographic tradition of symbols and attributes, we do know a fair amount of Plato’s life, thoughts, and interactions in the physical world from textual sources.

British philosopher David Sedley posits that the mosaic must be read by paying attention to symbols placed above each figure’s head. For the figure believed to be Plato, the symbol is a tree. Sedley argues that the tree in the mosaic is a 'plane' tree (Greek: platanos) based on its appearance, but more importantly for its semantic connection. In Greek, the word platys means plane or broad, and is the root of both the tree’s name — platanos — and Plato's own name (Platon). Plato was likely not the philosopher’s original name (probably Aristocles), so it was suggested even in ancient times that Plato was assigned this nickname for having a broad forehead, broad shoulders (he was allegedly a wrestler at one point), or a broad and expansive mind.

Plato himself makes the linguistic connection between his name Plato and the platanos tree in his dialogue, Phaedrus. We also learn in the Phaedrus that many a conversation at his Academy were held under the shade of a grove of plane trees.

Now we’re really getting somewhere.

But I'm burying the lede. The eye is naturally drawn to this figure because he is holding some type of rod and pointing (or drawing). What is he pointing at? If we follow the rod we come to a shadow by his foot. One of Plato's most well-known philosophical positions (his theory of Forms) is told through the allegory of shadows in a cave. The shadow in the mosaic may be alluding to this 'symbol' of Plato, but there is also something unusual about that shadow: it's composed of the darkest tesserae in the mosaic surrounded by the lightest ones, and is oddly oblong.

There are few other shadows in the scene. Even the sundial right above the figures is visibly casting no shadow at all. Could the sundial suggest that the shadow by “Plato’s” foot is referring not to the time of day but to the time of life in which the slouched, haggard figure finds himself in; that is, at the sunset — the end — of his life?

Holding that thought for a moment, we can continue to follow his rod to a sphere in a box. The sphere may be a symbol reflecting one of Plato's most fundamental (and complicated) philosophical arguments related to the divine and physical creation of the world, as told in his texts the Timaeus and Phaedrus. The narrator of Timaeus remarks that an accurate oral account of celestial motion is limited, and a visible model is needed to fully describe it (40d2-5).

Where am I going with this? This mosaic was not created for us, this future class of spectators, but for a contemporary purpose. Just as each individual tessera in the mosaic is necessary for the existence of the whole scene, yet individually they are meaningless, the specific components of the mosaic (e.g. Plato's slouch, the plane tree) appear unimportant until placed together to both support and confirm the overall context of the scene.

In David Sedley's view, the context -- the purpose -- of the mosaic is to depict the succession of leadership of the Academy after Plato's passing.

The contenders are the three figures holding scrolls. Just to the left of Plato, his nephew Speusippus sits distracted by another conversation, his scroll unopened. Above his head floats a dead (philosophical?) branch of Plato's tree. He did inherit the Academy for eight years after Plato's death, but disagreed and departed from many of Plato's positions.

To the right of Plato, an empty spot, perhaps vacated by the figure who is leaving the scene to the far right: Aristotle. Disagreements between the two philosophers, particularly on the topics of Phaedrus and Timaeus as represented here by the sphere, led Aristotle to relinquish any claim to the succession of Plato and to found his own school at Lyceum (which may be what is depicted in the top corner).

The man to the left of Aristotle, still enraptured in conversation with Plato, would become the successor of Plato's Academy: Xenocrates. There is a visual marker of Xenocrates' posture in text in which Xenocrates is described as having his "leg is drawn back" (Sidonius Letters 9.9), but other than this unusual reference we must rely on the scene as a whole to identify this man. Once we have identified the individual components of the scene and tied them together into the overall narrative, then, according to Sedley's interpretation, the message of the mosaic is to identify Xenocrates as the true successor of Plato's Academy and the philosophical school of Platonism itself.

Remember that this mosaic was preserved from the volcanic eruption Vesuvius in 79AD, yet Plato died around 348BC. The mosaic wasn't created during Plato's life but long after. Perhaps it was part of an artistic tradition that had propaganda-like aims to support Xenocrates’ direction of the Platonist school in the fierce competitive philosophical battleground of the Classical age.

A LOGICAL CONCLUSION?

I go into detail on this interpretation of the mosaic not because I believe it has any more merit than any other interpretation of this scene, but to give a sense of the kinds of logical connections, estimates, and leaps of faith that sometimes must be made to figure into what a scene is depicting.

Like the misleading shadows of reality that flicker in the cave of Plato’s allegory, when confronted with an ancient image that has no immediate mark of identification, we must marshal what knowledge we have to understand its form and purpose.

Surviving textual evidence is often the best -- and sometimes the only -- resource that we have to understand history. When the German polymath Goethe gazed upon Raphael’s School of Athens in the Vatican, he felt it was “as though one were supposed to study Homer in a partially-obliterated, damaged manuscript”. He was dissatisfied with his first impression. Only after he had visited again and again and “gradually examined and studied everything” did he feel delighted and whole. This is similar to Sedley’s interpretation of the Pompeiian “Plato’s Academy” mosaic; an analysis of the context of the whole scene is needed to grasp the message.

The problem is that we are limited in our toolset. The textual evidence we have is in fact from many obliterated and damaged manuscripts which makes it impossible to ‘study everything’. In both Raphael’s piece and the Pompeiian mosaic, the identity of Plato has never been constant. In Raphael’s case, the earliest written evidence interprets the scene from a more heavily laden Christian lens such that the piece is described as the biblical episode of St. Paul preaching in Athens. Later, in a Classically infused, Englightenment world, it began to be seen as Plato and other pre-Christian intellectual figures.

No wonder then that despite our drive to know, and limited by our perceptible toolset, we may end up incapable of ever truly knowing what reality stands behind the shadows playing in front of us.

Further Reading

Elderkin, G.W. 1935. “Two Mosaics Representing the Seven Wise Men.” American Journal of Archaeology. 39.1 (1935): 94-95.

Gaiser, K. 1980. “Das Philosophenmosaik in Neapel. Eine Darstellung der platonischen Akademie”, Abhandlungen der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Heidelberg.

Griffiths, A. 2016. “Navel-Gazing in Naples?: The Painting Behind the "Pompeii Philosophers"”, Syllecta Classica 27 (2016): 151-166.

Miller, S. 2009. The Berkeley Plato: From Neglected Relic to Ancient Treasure. University of California Press.

“Raphael’s School of Athens: Greek Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance”, Antigone Journal 02/2023. Accessed 14/07/2024.

Rashed, M. 2013. “La mosaïque des philosophes de Naples: une représentation de l’académie platonicienne et son commanditaire”, Omnia in uno: Hommage a Alan Segonds. Paris.

Sedley, D. 2021. “An Iconography of Xenocrates’ Platonism”, in Authority and Authoritative Texts in the Platonist Tradition. Cambridge University Press.

If you're interested in reading the full arguments of each position please see the Further Reading section at the bottom of this essay.

Very entertaining post, as usual. After AP David's post I may never think of Plato the same way again.

I enjoyed this post and all your work so far. I would point out that Antisthenes, an older disciple of Socrates said to be a rival of Plato, wrote a work responsive to Plato called ‘Sathōn’ or ‘Little Dick’. This rather suggests that Aristocles’ nickname (‘Broad’, ‘Platōn’) also refers to this part of his anatomy. It seems unlikely to me that foreheads or stooped shoulders would inspire nicknames from youth. It should be remembered that unlike our own, and boys in most of their contemporary cultures, Athenian boys were regularly without clothes in the gymnasium (‘school’, but literally a place of nudity). It seems more likely that such a nickname would have originated amongst naked young wrestlers, who unusually in our context did not belong to a culture pathologically repressive of the phallus, to the point where it must not be seen at all costs. In Athens, an unusual one might well have been identifying in a friendly way.