When did Western Europe become the centre of Ancient Greek scholarship?

From medieval universities to archaeological digs (Transmission Pt. 4)

This is the fourth and final article in a series that describes the transmission of Greek texts from antiquity until today. You can read from the beginning here.

Let’s start with a story.

It’s a hot summer day in 1167AD. The halls of the Toledo Cathedral are baking as the sun beats mercilessly upon Iberia’s arid interior. A man named Gallipus places his finger on a page of the broad book in front of him, clears his throat, and enunciates the Arabic text which carries the meaning of Aristotle’s Physics. His voice reverberates through the hall, ochre in colour, muffled mainly by the sweaty seminar of eager scholars and patrons crowding underneath the rows of horseshoe arches. Few of them can understand Arabic, so they wait for him to finish his line so he can translate it to Latin.

The only problem is his translation doesn’t help that much either. Gallipus, you see, has lived in this region his whole life, so he speaks Arabic, the language of scholarship and of the Islamic rulers who had been pushed out of Toledo within living memory, and Latinus, the everyday language which had descended and transformed from the Latin of the Roman Empire. The rest of the room is filled with foreigners from across Europe who studied a classical form of Latin and ventured to Toledo, drawn in by the reputation of the wise philosophers and their priceless Arabic scholarship found nowhere else in Europe. Many of the Greek and Arab authors they were learning of in Toledo had been completely unknown to them before.

The foreign scholars want to get the meaning of Aristotle right, and to return to their churches and universities with valuable copies. To that end, an English philosopher, William of Morley, pipes up to suggest an interpretation of Aristotle’s line as Gallipus read it. The Frankish archdeacon of the cathedral, who financially supports a large amount of activities like this, ventures another suggestion. Others join in the debate.

Gallipus ignores the discussion and looks over to the hunched figure across from him, who is sitting at his own desk scratching away in a blank manuscript with one eye perked to the jostling of the group. This is the man for whom Gallipus is working. It’s Gerard of Cremona from northern Italy, who had been working with Gallipus for years by this point and had become comfortable in both Arabic and the local Latin dialect. Looking up from Gerard, Gallipus looked now at the students and scholars around the room, whose cheeks were red from the heat and the excitement of the moment. He wondered how far his voice would travel through Gerard’s copies; who would go on to produce seventy translations. How far would the scholars fan out across Europe, and how long would the books survive? Would the Latin translation convey the true meaning?

He saw now that Gerard’s wide blue eyes were looking right at him, waiting for the next line, so Gallipus cleared his throat again and placed his hand on the undulating, yellow page. As he enunciated the Arabic, he felt the thick parchment between his fingers. He thought about the history of his own book right in front of him. It had been brought here hundreds of years prior from the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where it was written in Arabic for the first time. Some text in the margins of the book is still in Syriac, which was probably the language the text was in before Arabic. And of course, long, long before that – in the mists of time incalculable for Gallipus – through libraries and scrolls and monasteries, the words in the Physics had allegedly been uttered by the great philosopher Aristotle in some magnificent lost city called Athens across the Mediterranean Sea.

In the previous article, I discussed how the transmission of Greek texts had splintered into three broad threads starting roughly in the 5th century AD. The Byzantine (Roman) empire was copying and focusing on Greek literature and history. The Arabic Muslim courts and schools dutifully translated and advanced the ancient Greek science and math. The third thread in western Europe became essentially dormant as Greek knowledge was extinguished.

Yet in this story we see the three threads coming together again. We see northern and western Europeans seeking out Greek texts, translated as they were through several languages, in an Arabic tradition that had recently become accessible through Christian conquering of land in Iberia. How did western Europeans learn to engage with Greek scholarship with such sophistication, energy, and diversity? What did they do with this knowledge, and how did they have the apparatus to appreciate it?

Innovation 7 - University

After the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, mostly illiterate Germanic leaders ruled over disunited and warring tribes with little control over their lands. Economic activity was greatly reduced, the wealth and health of most people declined, and cities were emptied out as people needed to move to the countryside to raise their own food. Most surviving texts ended up in monasteries, and just a few high members of the nobility and clergy may have been able to read Latin.

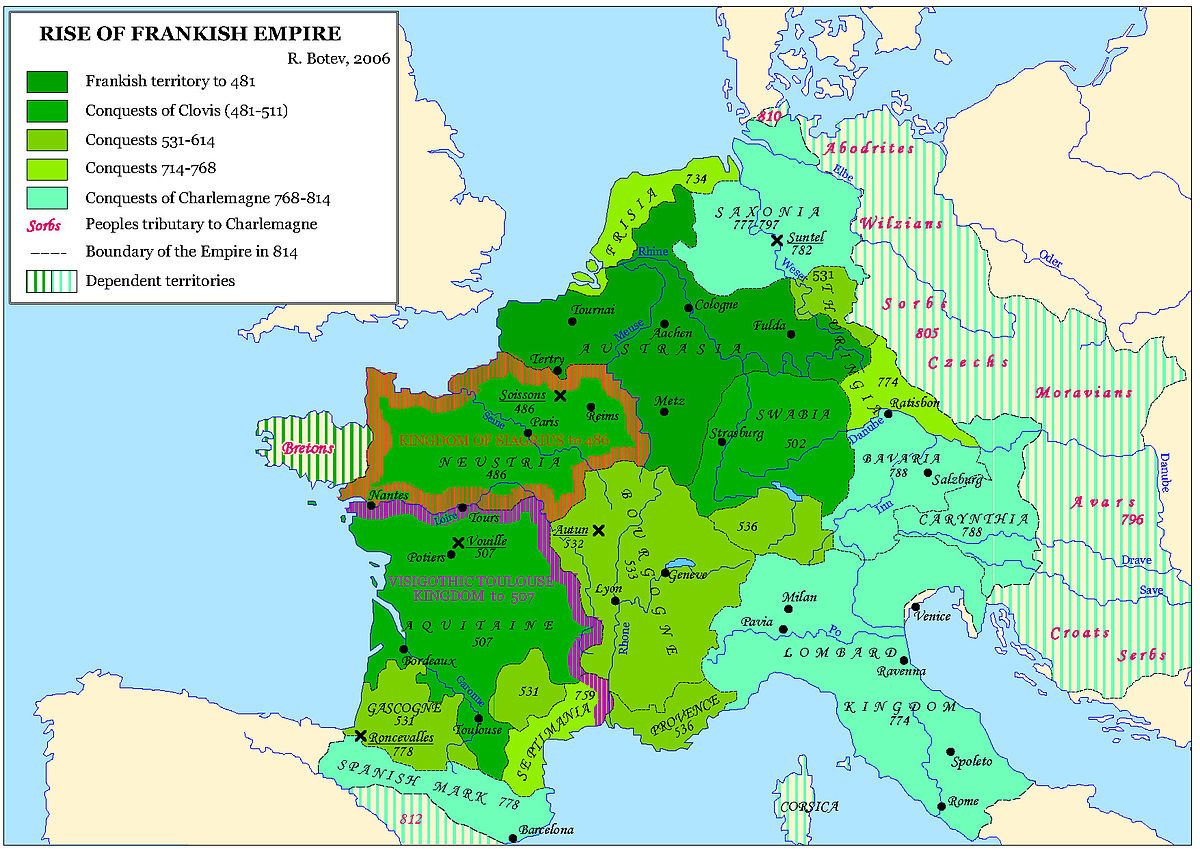

By the 8th century, one of these tribes, the Franks, grew into a powerful kingdom which would eventually rule Western Europe under a united crown larger than any seen in centuries. The most powerful monarch of this period, Charlemagne, eventually conquered the Italian peninsula down to Rome, and was subsequently crowned Emperor of a renewed Roman Empire by the Pope in 800AD. Part of this imagined renewal of the Roman Empire was produced in Charlemagne’s support of literacy and learning, which he could see was in a sorry state. Texts were drawn from throughout Italy and elsewhere and copied in the royal court, and an imperial edict was pronounced to attach schools to monasteries and cathedrals.

In truth, the “Holy Roman Empire” as Charlemagne’s empire would come to be known, was only dubiously a continuation of anything Roman. After all, there was already a Roman Emperor in Constantinople, the privileged head of Christendom for centuries. But as the divisions between East and West Europe deepened, the Pope perhaps found it expedient to have a favourable monarch close at hand rather than a distant, Greek speaking empire embroiled in its own controversies. The Greek language was entirely extinguished in the west by this time, and even Charlemagne’s Latin schools didn’t last long, but they did have the effect of re-copying a great number of Latin texts that may have been lost otherwise. These texts fostered an interest in classical knowledge, and could be taken up in the coming centuries by an institution of scholarship better equipped to appreciate them. Enter ‘the university’.

Charlemagne’s empire ultimately splintered and formed the powerful Kingdom of France as well as a series of small German and Italian princedoms and states. In the 10th and 11th centuries, the level of wealth, sophistication and complexity in western Europe finally began to match that of the Roman Empire over half a millennium earlier. The relatively small, competitive states of the time resembled the city-states of ancient Greece with their trade, conflicts, and hunger for knowledge that exploded onto new scenes. The Church was influential but kept in check by the growing secular power of the courts and economies across Europe, which allowed for a great element of cross fertilization and freedom for scholars. Knowledge was drawn on the one hand from libraries and clergy of the Cathedral schools and monasteries from Charlemagne’s time, and on the other from the collections of noble courts and apprenticeships that were making Europe anew.

New methods and institutions were needed to develop a professional class capable of meeting the demands of the increasingly complex societies in western Europe. Scholars from different educational, religious, linguistic, and national backgrounds met in the growing cities to debate how best to interpret the archaic Christian scriptures and classical Latin texts. During this process of debate, they gave rise to the Universitas. These aren’t universities as we think of them today, they were rather like a corporation or a sworn guild based on bonds of men just like those that had formed for trades like carpenters and tanners. The purpose of this guild of knowledge was similar to those trades, too; they could create vocational professionals like scribes, secretaries, speech writers, and eventually doctors and lawyers around a structure of collective bargaining to support both students and teachers.

There was no physical institution for the scholars until the thousands of students who flooded into cities had caused such a ruckus with local townsfolk that colleges were formed to help house the students and keep them out of trouble. As the universities grew through the 12th century, the students and faculties formalized. Specialties developed, such as theology in Paris and law in Bologna. But the mobile nature of scholarship was never lost, as a base curriculum in the classical liberal arts of the trivium (rhetoric, grammar, and logic) was shared across all universities and students could jump from university to university to complete their degree. Upon completion, those students possessed licenses to teach anywhere in Europe.

This profusion of intellectual interest resulted in a vast amount of texts being created, whether original or a copy. Debates between students and teachers were central to the university, as with many intellectual pursuits discussed in this series. As they aped Greek forms of knowledge production like the Socratic Dialogue (or disputations, as the medieval universities called them) and the classification systems of knowledge from Aristotle, they sought out new Greek texts. They knew of the respected Arabic scholarship, and many travelled to accessible Spain in western Europe in order to bring new texts into their institutions. Although even as Greek philosophy and knowledge influenced western Europe’s society and religion, none of it was conducted in the Greek language.

The largest amount of Greek-language texts which would go on to fuel the Italian Renaissance were to come from the Byzantine Empire. From the late 11th to 13th centuries, the beleaguered Byzantine Empire requested aid from the west to help reclaim the Holy Land in Palestine and to repel the Turkic invaders. Despite this request coming shortly after the 1054AD Great Schism which formalized the split between the Western Latin Catholic and the Eastern Greek Orthodox Christian churches, the response from the west for these Crusades was tremendous across all backgrounds. The knights of the west, feeling their Christian faith had been only strengthened by the renewed vigour of reason and logic that was accompanying it, travelled thousands of miles and through the heart of the Greek speaking Byzantine empire to fight.

Prior to the Crusades, for most westerners, the “Roman Empire” and the fabled fortress of Constantinople – the first Christian capital – was the stuff of legend. These travels brought greater understanding of Christianity, Greek culture, and imperial power hitherto less appreciated by the west. However, the tensions between east and west remained from the Schism. In the 13th century a new type of crusade was launched by a new Pope in Rome. Instead of targeting the Holy Lands, the target was Egypt, and the Byzantine Empire was not involved. The Latin crusaders, penniless from needing to pay for a massive naval fleet for the mission, turned their eyes to Constantinople itself and sacked the city which had stood impregnable since time immemorial. It is likely that in this moment, when the crusaders ruthlessly looted the treasuries and burned the city, that more Greek texts were lost than in any other time.

One silver lining to the sacking of Constantinople for the transmission of Greek texts, despite the destruction, was that there were greater Latin-Greek linguistic connections in the court of Constantinople and western Europe. East and West were beginning to speak each other’s’ language. For example, the first Greek school in western Europe in over a thousand years was established in Florence in 1397 by a Greek cleric and diplomat, Manuel Chrysoloras, who initially travelled to Italy to try and lessen the divide between the Churches.

Latin speakers had set up in Constantinople and were enticed to bring whatever texts they could find to their universities back in the west. As the Ottoman Turks advanced closer and closer to complete takeover of the Byzantine Empire, more and more Greek texts – sometimes in the hundreds at once -- went with Latin humanists and Greek refugees to Italy, which by the 14th century had become a centre of humanism and classical learning.

These processes over hundreds of years continually added to the libraries, wealth, and prestige of western Europe. With a greater knowledge of Greek and Latin amongst all parties, and armed with original Greek texts, remarkable new insights could be gleaned that would eventually power the Italian renaissance of the 14th to 16th centuries.

By the 16th century, the flourishing of Greek interest in the Arabic tradition in Spain and across the southern Mediterranean had long since come to an end. Another Islamic power, the Ottoman Empire, eventually conquered Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire in 1453AD. The imperial Roman Empire which had once taken up the mantle of Greek learning and then fostered Christianity, despite whatever schisms, had come to a definitive end. Almost all the Greeks were now within the Ottoman Empire, and effectively cut off from the advances and developments in the west precisely at the moment of the west’s devotion to ancient Greece – from the Italian renaissance to the scientific revolution to the enlightenment – until the independence of Greece in the 1800s as I discussed in the first article in the series.

As the Ottoman Empire continued its advances all the way up to the edges of Vienna, Western (and northern) Europe was the primary bearer of Greek texts, and felt themselves in some way the protector of Christianity. Perhaps feeling cornered and pressured at an edge of the world, yet logical and self-righteous, the Europeans soon set out on globe spanning missions of exploration alongside technological and political breakthroughs that continue to shape our world. These developments were aided in no small part due to their reception of Greek knowledge and thought.

This extraordinary length of transmission can be centered on the university with credit due to the previous innovations, because the university represented a repository that was essentially designed to analyze, collate, criticize and produce all kinds of information and texts, including the highly valued work of the ancient Greeks. Although this process alone may have ensured the transmission of Greek texts, they were still in a relatively small number. The following innovation, the printing press, would ignite an information revolution that would see Greek texts eventually spread in the millions.

Innovation 8 - Printing Press

The technique of imprinting images or patterns onto cloth using carefully cut blocks of wood covered in ink became very popular in Europe by the 14th century. The technique was even older in China, where it was also one of the primary ways to create copies of texts. However, in Europe it was never used for printing texts any longer than what you need on a playing card or religious icon. This was partially because of the Church’s insistence and the public’s taste regarding the beauty and importance of handwritten documents.

In the 1430s and 1440s, a process of invention capped off by Johannes Gutenberg resulted in the creation of the European moveable type and printing press. Both handwriting texts as well as using woodblock printing were extremely long processes. The utility of moveable type was that individual letters could be cast, set into a frame (text-block) with the infinite possibilities of writing, inked and then pressed onto the writing material. Ink could be re-applied and new pages pressed onto the template for as many copies of that particular page that was needed. The process up to this point was still extremely laborious, as casting hundreds of letters took a huge amount of time, let alone the construction and design of the large press. The efficiency in this design was that unlike woodblock printing, those letters could now simply be re-combined as a new text-block that would create a brand new page, again and again ad infinitum.

Using his new invention, Gutenberg soon printed one of the most famous editions of any text in the world: what is today called the Gutenberg Bible. This was published in a print run of 180 copies in 1454 or 1455. Soon after, his inventions were spread across Europe, and Latin texts were printed at an alarmingly quick pace.

The first Greek book to be printed was the Erotemata in 1471, which was a Greek grammar for Latin readers to be able to understand their Greek texts. Most of the early printed Greek books were designed for learning Greek. The first ancient Greek text printed was likely the comic epic Batrachomyomachia (Battle of Frogs and Mice) in the 1470s.

Despite the increased interest in Greek texts in the late medieval period, getting the Greek press off the ground was still a difficult venture for many reasons. Many people didn’t realize or appreciate the Greek as the initial language of a text. One Greek scholar in Rome, Bessarion, helped establish that if there was disagreement between texts that the Greek, instead of the Latin, should be taken as the authoritative text. A method in the universities was developing to compare and understand different versions of manuscripts and their respective strengths and weaknesses, which leads to the modern scholarly tradition of textual criticism.

This valuation began to extend to Christian texts as well, although the method of prying open a Bible and critically engaging with it was not always wholly welcome. The common form of the Bible in western Europe was in a Latin translation called the Vulgate, which had been in use since the 4th century. However, a Dutch scholar named Erasmus established that the Greek version of the Bible is older and more authoritative than the Latin in many respects. He printed the first edition of the Bible in Greek in 1516, which later became known as ‘textus receptus’ and as the basis for much Christian theological study. Simultaneously, printed books and a meteoric rise in literacy made reading the Bible in various translations possible for more people than ever before at the precise moment that many were growing increasingly alienated by excesses in the Church’s governance and hierarchical structures.

People wanted to engage with the earliest scriptures in the Christian tradition, and realize God more on their own terms than solely through clerical intermediaries. In 1517, one year after Erasmus’ Bible was printed, the German professor of theology Martin Luther wrote up ninety-five theses as a point of debate on Church practices which ultimately led to the Protestant Reformation and the birth of a new branch of Christianity. Although Erasmus was never a protestant and Luther didn’t intend to create a new sect of his religion, this episode shows how the processes of engaging with Greek texts and their transmission were still transforming societies millennia after their production (and without necessarily being about 5th century Athenian philosophers).

With interest in Greek texts of Christian and classical natures secured, the printing press had a better shot of getting of the ground. The main Greek printing press was in Venice, where most Greek refugees had congregated and the city with the highest output of printed material in Europe. A man named Aldus Manutius with his Cretan assistant Marcus Musurus ran a Greek printing press, creating many fonts including the Aldine font that are influential until today, and creating the first printed editions of both major and less known Greek texts. The print runs even of Greek texts (which were much lower than Latin) could be up to 1,000 copies per run and were far beyond how many texts could be produced when they were laboriously copied out by hand by a small number of scribes.

When making a printed copy of a handwritten Greek manuscript, sometimes just a single manuscript of it was available for reference by the printer. Sometimes they had multiple manuscripts, but primarily based their print off of one version. After the manuscripts were used, they were often discarded or neglected without purpose. This fate is shared by many papyrus scrolls and majuscule manuscripts during earlier periods of transferal which I outlined in earlier articles in the series. Unfortunately, sometimes the printer made mistakes, or erroneously considered one manuscript authoritative over another. This has made more difficult but also more necessary the process of trying to correct the mistakes or to simply better understand the genealogy of different traditions of thought and book production, which is a large area of the field of research surrounding Greek texts.

By 1550, if one were to collect all the available scholars and Greek texts available, we would see that as a result of the Renaissances of the medieval and early modern periods that they had almost as much literature of Rome and Greece as we have today. And they could read the texts (or learn to) relatively easily and cheaply in printed copies, both in their original languages and in translations into vernacular languages. There were multiple editions of the same text that continued to improve the text.

Greek texts went on through the 16th century and beyond to help understand and develop European society, religion, technology, politics, warfare, medicine, and science. They would influence European art, poetry, and literature in surprising and subtle ways. There are countless important events in these time periods which all continued to ensure the transmission of Greek texts that fanned out across the entire planet riding along the innovations of the university and the printing press.

Innovation 9 - Modern Science and Archaeology

In the centuries that followed the printing press, Greek texts were in no danger of falling out of use. They were continually printed in new editions, with improvements and corrections based on new manuscripts coming into the possessions of the libraries and universities of Europe. Greek texts played a key role in intellectual movements of Europe and beyond, even as Greek texts were finally superseded by new research and methodologies, such as Copernicus’ revolution which placed the sun firmly in the centre of the ‘universe’ instead of the Earth. From the Reformation to the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, Greek texts were still important all throughout.

New texts coming to light weren’t (and aren’t) simply discovering new manuscripts or fragments from monasteries and lost collections. In 1715, hidden beneath a page of a 6th century AD New Testament in Latin was spotted several lines from a copy of lost Greek play by Euripides’ called Phaethon, which was originally staged in 420BC. The process of scraping or washing off old text to replace it with new text is called a palimpsest. There were many points in time in the long story I have thus told where it made sense to erase old text in order to write new text more cheaply than trying to produce a new and expensive book from scratch in economically difficult times. These palimpsests have uncovered many new texts that were hitherto unknown, and new technology helps us read them.

More importantly, however, are the finds of ancient papyri (and some parchment). People who know a little bit about this topic may have been scratching their heads about my apparent mistake in missing these papyri through this whole series. I said in the first article of the series that we don’t have texts from the classical Greece of 5th century BC, or from an ancient Greek author’s hand or even their own lifetime. That’s true. But since the 1800s, more and more papyrus with ancient Greek writing have been discovered that are as old as the 3rd century BC and going as late as the 6th century AD. These are almost invariably the most ancient extant Greek texts we have on the topic, whether it’s a classical Greek epic poem, a Christian text, or just everyday administration or life in the Hellenistic or Roman empires.

I have thus far avoided discussing these papyri because they aren’t part of the intellectual transmission of Greek texts. Most of the people discussed in the innovations so far had no access to any of these texts, which were either buried in the desert in a provincial Egyptian town called Oxyrynchus until 1896 or underneath ash from the Vesuvius eruption of 79AD in Herculaneum until 1752. Many didn't make it to the transference to books after the 2nd century AD or into the libraries of monasteries after the 4th century as they were already lost. A huge thread of ancient Greece has only recently rejoined the growing weave of Greek texts.

The texts from Herculaneum in Italy comprise nearly 2,000 carbonized papyrus rolls from the only extant library from antiquity. They are extraordinarily difficult and sometimes impossible to unroll and read. If one tries to unroll the carbonized roll, it often falls apart or at the very least the text soon becomes invisible. With advanced technology today, some are becoming able to be read by digitally ‘unrolling’ the scroll in order to read it.

A vast number of papyrus and parchment scraps were found over thirty feet deep at Oxyrhynchus starting in 1896. Over 86 volumes of edited texts have been published based on these findings. Yet what has been edited and published makes up just a tiny fraction of the overall number of fragments discovered. The work is extremely slow and meticulous, as most papyri survived as only tiny scraps. Of those that are edited, most are of everyday aspects of administration and bureaucracy and private letters, many others are of Christian nature, and just a small percentage are of Greek classical texts (although most are in Greek). But of those, it still yields a massive amount that over the last century has already transformed the understanding and library of those texts. Some of the texts are otherwise lost except for these papyri, especially those of Athenian playwright Menander who lived in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

We are currently living in the midst of this innovation, and with hindsight it will be easier to comprehend its story. In any case, there is certainly greater and easier access to a larger catalog of Greek texts than ever before, perhaps even classical Greece. With digital technology and open publication, it's easy for anyone to see or read the originals or at least translations of the stories, something that monks and scholars of the past eras wouldn't have had. Even in Greece itself, only those in certain cities could perhaps attend plays or hear the political dialogues in the town squares.

Conclusion (Looking Back)

In the 21st century, there is now the most stable and wide-reaching engagement with Greek texts since antiquity. For over 500 years the transmission and valuation of classical texts has essentially been assured, just as it would have seemed back in Greece. Perhaps in some ways it appears even less likely that the transmission and preservation of Greek texts could be interrupted than ever before. This is one reason why it is easy to take for granted that facts, quotes, and whole books from a society thousands of years prior to our own seem to integrate seamlessly in our lives. We often don’t think about how those texts reached us, how they can be imperfect, and how incredible it is that they have done so both because of and despite human intervention.

The dialectic between oral and written forms of knowledge creation continues to this day to produce new knowledge and copies of ancient Greek works. That knowledge is transmitted in books printed on paper or one of countless digital formats, whether in Greek or English or Japanese or many languages and any font. The knowledge is produced and housed in libraries, monasteries, museums, universities, and laboratories, not to mention adaptations in student plays, Hollywood movies, video games, and children’s imaginations.

The complex, urban world of ancient Greece that gave rise to Greek works and the sophisticated cities of late medieval Europe that gave them new life are both far surpassed by the specialized complexity of our own world. We use all the innovations before us to utilize Greek texts, but this doesn’t make the historical process inevitable. As discussed in the two previous articles, in the late antiquity and early medieval periods in western Europe societies built for the classical mode of life were utterly transformed economically and religiously, which altered textual engagement. Countless Greek texts were lost in historical moments like those, while others sometimes barely survived through a single individual copying the last copy of a text.

Collectively, ancient Greek works in recent times are viewed with more than historical importance; they continue to possess the ability to illuminate mathematics and science, engage with artistic and literary conventions, and ignite wonder, passion, and frustration. So too did many of those in the past value Greek works. Whether in cities or not, whether in Greek or not, whether in Greece or not, whatever religion, whatever philosophical bearing, the process of transmission shows the shocking malleability of the ancient Greeks to be integrated into knowledge systemizations and development of identities. Again, however, this valuation is not inevitable. Specific Greek works can be argued against for the development of a Christian doctrine, or simply ignored in favour of the enticing discussion of the day, as during the Byzantine iconoclasm movement. They can also be lost indiscriminately by wars or the fires of time itself.

The complex and sometimes random process of transmission and preservation means when you read an ancient Greek text, or a referenced line from Greek mythology, history, or science, it has more or less followed the high-level overview outlined in this series. The oldest extant text could be from a hundred tiny fragments of a 3rd century BC papyrus scroll, or a few pages of palimpsest underneath the text of a Latin 4th century parchment manuscript, or re-translated from the paraphrase of an Arabic scholar writing on paper, or in a tiny font in the margins next to a 10th century Byzantine encyclopedia written on vellum by an anonymous monk, or printed in a bound book by a fledgling print house in the 16th century. A complete text is incredibly rare, and always has been, so in a modern edition of a text there will be an interpretive combination of extant texts which themselves were probably an interpretation and collation of whatever extant texts the person compiling those texts had. Despite all this, Greek texts are some of the best preserved and with the oldest and most comprehensive system of scholarship around them when compared with other ancient textual traditions. All these factors enable a modern audience to enjoy the tragedies, hilarity, and genius of the ancient Greeks.

This article is the final high-level chronological overview in this series on the transmission of Greek texts, although in the future I aim to develop visuals like timelines and maps to help communicate this complicated story. In the next article, I will provide a bibliography of sources for my research, and outline how anyone with curiosity can follow similar trails of history through primary and secondary source material. I will also outline some of my favourite general materials like podcasts for this subject.

If you are interested in a closer look at the specifics of transmission, in a future article I will follow a single line of text through the thickets of time to see how it made it to today. What hands did it pass through? On what material? In what location? What was the context for its creation? I’m really excited about this one because it will be a whole new realm of exploration for me, where I will produce an investigative style of narrative out of my own notebook, highlighting the dead-ends, impossible leads, and (hopefully) the ‘aha!’ moments. I aim to then apply that textual trail right to a physical archaeological site in Greece and see how it has informed the material interpretation of history.

To see which books and resources I used to research for this series on Ancient Greek Textual Transmission, please see here.