Why people are earning millions to reveal text destroyed by a volcano

What do the Herculaneum scrolls say?

In October 2023, 21-year old undergraduate student Luke Farritor was awarded $40,000 for being the first person in history to uncover an ancient Greek word from an unopened, 2,000-year-old scroll. Eight letters forming the word ‘purple’ (ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑΣ) may not sound like a lot, but it was a feat previously thought impossible.

Why?

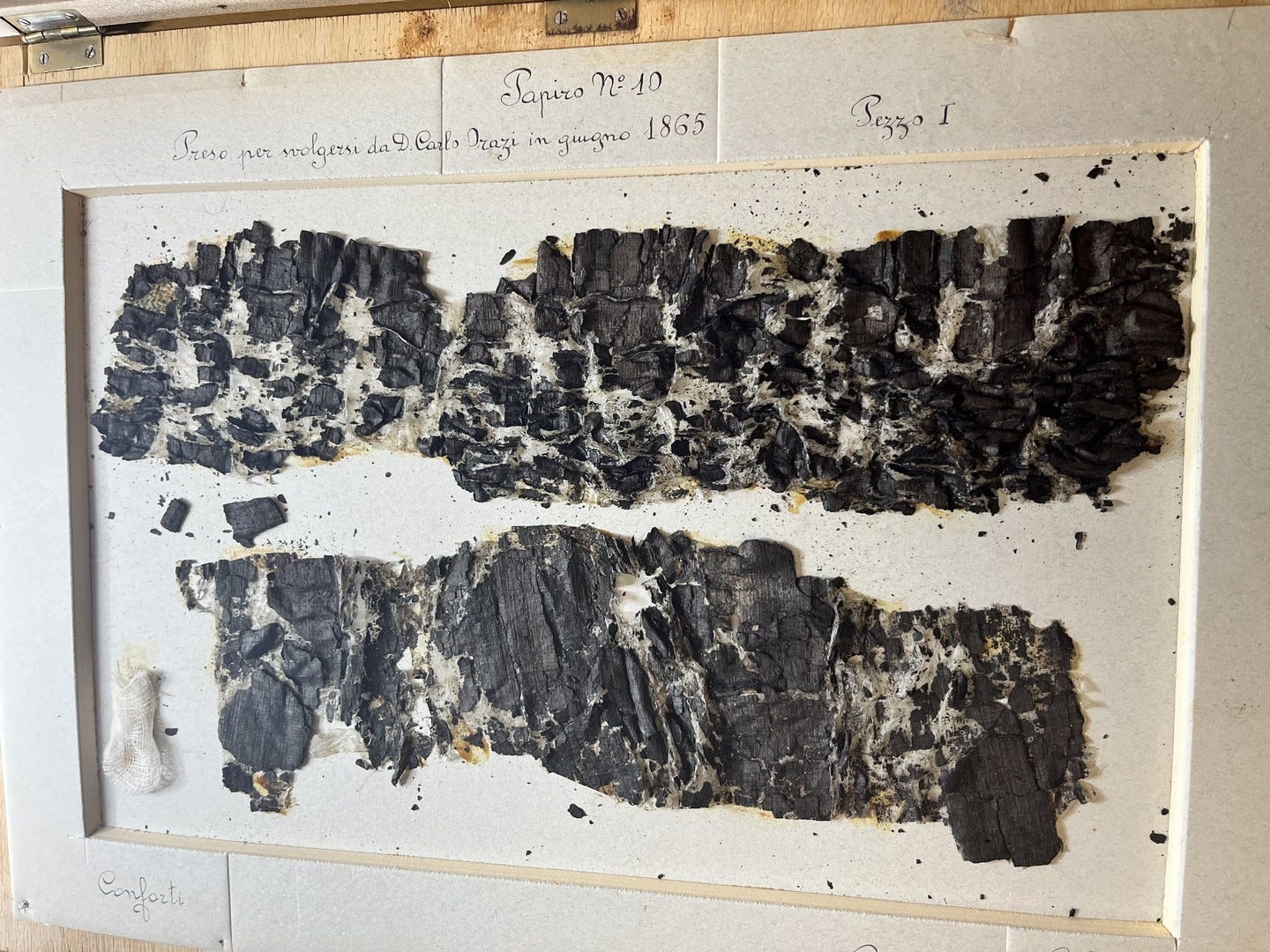

Here’s what the scroll looks like.

In February 2024, just as the ash settled on this breakthrough, Farritor and two other students were awarded $700,000 for uncovering fifteen columns of text with hundreds of words1. The pattern of discovery is becoming exponential.

The reading of the text is made possible through X-ray phase-contrast tomography. The X-ray makes thousands of ‘slices’ of cross-sections inside the scroll, and the resulting illuminations help detect slices of papyri with traces of ink on its surface. People like Farritor have then been able to detect ink and stitch together the cross-sections to create readable text.

The scroll was found more than 200 years ago just outside Naples, Italy, in an ancient Roman town called Herculaneum. Since its discovery, it has remained stubbornly impenetrable.

The scroll is charred and fragile from being subsumed within a pyroclastic flow from the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD. The same eruption destroyed the nearby city of Pompeii, but Herculaneum was impacted differently, being covered in up to 25 metres of pyroclastic mud. The mud was incredibly hot and — without oxygen or fire — did not incinerate or destroy items within Herculaneum. Therefore, there are remarkably well-preserved effects from Herculaneum such as papyrus, which formed the base of writing material for ancient literature.

Why are millions of dollars awarded for revealing text?

The scroll is hard to read, incredibly ancient, and relatively well-preserved, but why is it being valued so highly that those who can reveal its texts are being awarded millions of dollars?

The text revealed earlier this year had not been seen since antiquity. It was likely written by a philosopher named Philodemus, who is in dialogue on the question of how to enjoy life. The debate questions whether items in scarce quantities – like food or music – afford more pleasure than those same items in abundance. Philodemus thinks not, stating that less is not necessarily more.

In the case of scrolls, I’m inclined to agree with Philodemus. If this revealed scroll were the only of its kind, it may make the scroll more precious, but in fact the excitement – and the value in the new digital techniques – is that the scroll is one of 1,836.

The scrolls altogether form the only “intact” library which survives from the ancient Greco-Roman world. Around 90-99% of ancient Greek and Roman literature has been lost, and the bulk of those few percent which do survive are through medieval copies by monks and scribes. The copies are selective, transformed, fragmented, and sometimes unreliable, disagreeing with other medieval copies. We see the ancient past through the opaque prism of the medieval period.

The scrolls discovered at Herculaneum are a chance to sidestep the thousands of years of imperfect transmission of texts. They are primary documents written by and for actual inhabitants of the ancient past. Who knows what those texts could contain, untouched by human hand since the last time they were put on the shelf?

Were any scrolls previously unrolled?

The newfound ability to read inside unrolled scrolls is even more valuable because of what’s already been lost.

When the scrolls were first found, it was 1752. In the process of digging a well, the ancient Roman town of Herculaneum was discovered by accident. Lumps of charcoal were found and thrown onto the fire to keep the explorers warm. It was only later that these lumps of charcoal were recognized for what they actually were – ancient literature surviving in the same room in which their ancient creators wrote, read, and debated them.

Even once people realized they were looking at ancient scrolls with text, the scrolls were so fragile they fell apart to the touch. Trying to unroll them resulted in the pages crumbling away or splitting apart with multiple layers of the roll stuck together.

“It is not a month ago, that there have been found many volumes of papyrus, but turn'd to a sort of charcoal, so brittle, that, being touched, it falls readily into ashes. Nevertheless, by his majestys orders, I have made many trials to open them, but all to no purpose.” – Camillo Paderni2, the first person to try and systematically open and read the papyri in the 1750s

Over the next two centuries, methods have been devised to open up and read the black ink on blackened papyri. Some of these methods included hacking it open with a knife, scraping away its layers, pouring liquid mercury over it or other chemical compositions, and attaching animal membranes to each layer from which a machine could painfully slowly unroll the scroll.

A huge amount, perhaps most, of the text from those thousand-odd scrolls is lost forever.

In total, over half of the Herculaneum scrolls:

have been destroyed without a trace of the text

have been destroyed immediately after some text became legible

are partially legible but the ancient papyri is quickly turning to ash

The scrolls which remain unopened were considered even harder to open than those which were hacked open and peeled away. For centuries they appeared so insurmountable it has been considered foolhardy to even try and open them up.

That is, until computer scientist Brent Seales came onto the scene about twenty years ago. Seales helped pioneer the use of X-ray tomography to ‘digitally unwrap’ ancient and damaged scrolls. In 2019, a team produced the highest quality images of the scrolls yet. With those images and his expertise, in early 2023 Brent Seales launched the Vesuvius Challenge, from which Luke Farritor and others have now been able to reveal text in the scrolls.

As Brent Seales, Luke Farritor, and everyone else involved in the Vesuvius Challenge has shown, it is now feasible that the vast majority of the text from the 659 unrolled scrolls could become legible! Beyond those unrolled scrolls, some fragmentary scrolls may be able to be scanned and read, helping recover even more texts.

How much text is revealed in the scrolls?

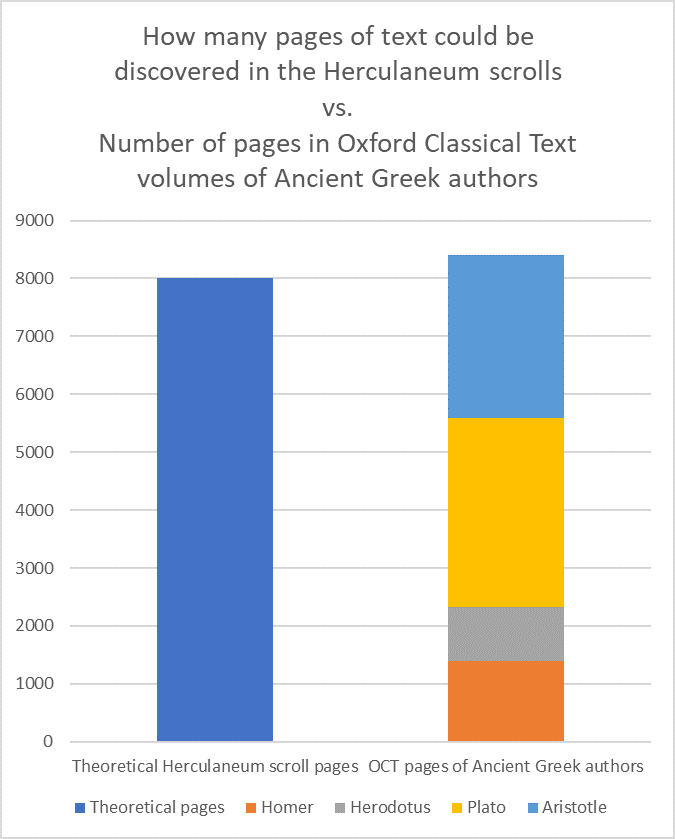

German classicist Kilian Fleischer estimated the unrolled papyri to measure out between 950 and 2850 metres, making up 15,000 to 43,000 columns of text – or about 8000 pages (up to 25,000 pages!) with 1.5 million words of text3. There are currently 144 volumes in the Oxford Classical Text collection, which makes up a huge proportion of literature in ancient Greek and Roman. If all the unrolled text were new, it could add 30 or even more new volumes to this collection. That would constitute by far the greatest finds of ancient literature since the Renaissance.

What text is revealed in the scrolls?

8000 pages is a lot, but what might they actually say? After all, the texts are only valuable for the content of the texts within them, regardless of how old the texts are, or how difficult it is to extract the texts.

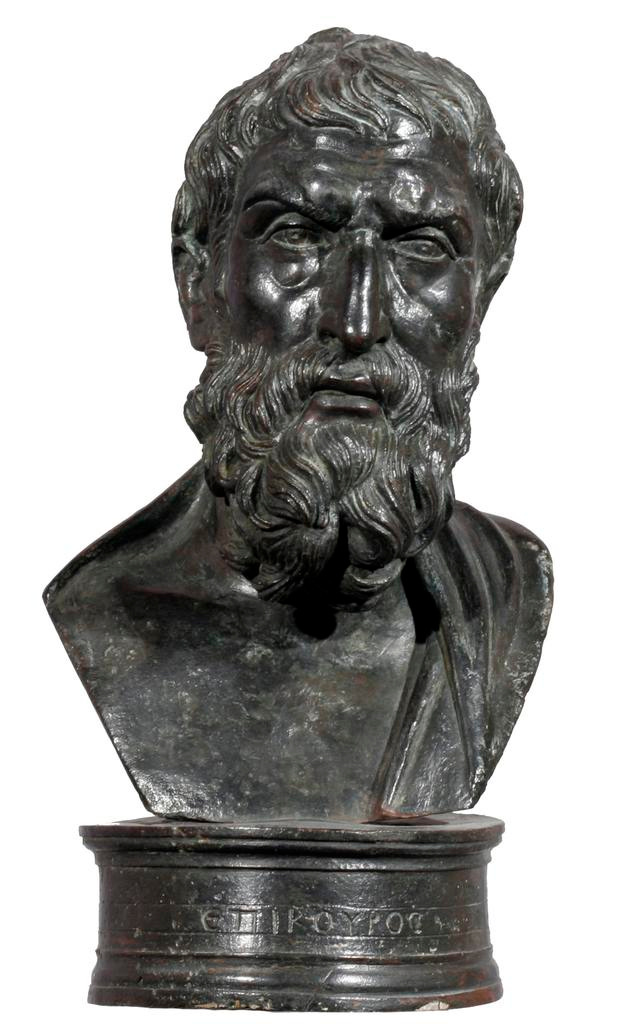

Most of the scrolls’ texts so far have been related to a philosophy called Epicureanism, which was founded in Athens in the 4th century BC by its namesake, Epicurus. Down the road from Plato’s Academy, Epicurus operated his own open-air school called the ‘Garden’ where his philosophy was developed, controversially, in a co-ed environment with men and women, citizens and slaves. Epicurus was one of the first people to theorize the existence of atoms, which he believed formed the basis of everything in existence and that events in the infinite universe are based on the interactions and motions of these atoms.

As a materialist philosophy which seeks the absence of pain as the ultimate goal, states that death is the end of a person’s experiences, and questions the existence of divine intervention; Epicureanism butted heads with competing Platonism, Stoicism, and – most fatally for Epicureanism’s transmission – Christianity. It is precisely because of Epicureanism’s lack of popularity with its more popular competing philosophies that it most fell into the side of 90-99% of texts that did not survive. These texts show how the Herculaneum scrolls present an opportunity to miraculously peer outside the selection bias that has dominantly shaped our view of ancient history that makes the scrolls such an incredible opportunity.

Who wrote the scrolls?

The suspected author of most of the texts uncovered so far is one Philodemus, who was educated in the Epicurean Garden of Athens around 90-70BC, some 200 years after its founder perished. Philodemus engaged with Epicurus’ and later Epicureans’ works and composed many of his own texts. It is likely that many of the scrolls are written in the hand of Philodemus himself (or an amanuensis) and constitute his own personal library of texts. If you have read my other essays on the subject of Greek transmission, you will realize what a revelation it is to have surviving, primary material evidence of a text written or composed by its own author!

However, the hope is perhaps that Philodemus won’t simply become the most well attested writer of ancient Greek that survives to the present, and that a more diverse range of texts will surface. Already several non-Epicurean texts have been uncovered. There are fragments of Stoicism, poems of the Battle of Actium between Octavian and Mark Antony/Cleopatra, and lost Histories by Seneca the Elder. In early 2023, another form of computed tomography helped to detect ink on a fragment of papyri which has already been open, and it shows a list of dynastic succession following Alexander the Great’s conquests.

The possibility of more lost texts that shed light on the ancient past remains a tantalizing possibility, especially if they will be more legible than the historic attempts to open and read the scrolls.

Are there thousands of more undiscovered scrolls?

The papyri scrolls were found in a massive villa, named the Villa of the Papyri, just outside the town of Herculaneum. The villa is believed to be a residence of the highest elected official in the Roman Republic, a Consul named Gaius Calpurnius Piso (who was also the father-in-law of Julius Caesar). In the 1990s, new excavations revealed that the villa had at least two additional floors below the floor that had been excavated and explored since the 1700s. The place where the current scrolls were excavated is thus the upstairs of the villa, and the thousands of scrolls examined thus far could simply have been the private working collection of Philodemus.

Some speculate that the lower floors, which would constitute the main part of the house and contain spaces in which highly-esteemed visitors would be welcomed, could house thousands of yet-undiscovered scrolls. Would any self-respecting Consul not have a main library which contained an impressive range of major texts of the Greco-Roman tradition?

It is this hypothetical main library that might hold the best chance of recovering the rest of Homer’s Epic Cycle, the lost poems of Sappho, scientific treatises from Aristotle, or illuminate knowledge of the founding of Rome or the culture of the Carthaginian Empire. It is even possible, although unlikely, that Jewish/Christian text could be recovered, particularly because St. Paul disembarked at Herculaneum’s neighbouring port on his way to Rome just 49 years before Vesuvius’ eruption.4

There are currently no plans to excavate the lower floors of the Villa of Papyri. Since 1999, the Italian government placed a moratorium on further excavations in Herculaneum (and Pompeii) in an effort to focus on conserving what has already been excavated. The ruins and finds of Herculaneum are incredibly valuable, but they are also precious and fragile. The scrolls which have been excavated were certainly preserved better for the 1,700 years they spent under volcanic mud than in the 250 years since their excavation. Perhaps future technology will allow texts to be read without them even being dug up, just as cutting-edge technology is allowing unrolled and carbonized scrolls to be read today.

For now, the proof that it is possible to read text within the hundreds of unopened scrolls is reason enough to be excited. After decades of work and millions of dollars spent, the first word, ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑΣ, became legible in October 2023. Just a few months later, hundreds of words were already legible, which make up 5% of one scroll.

The Vesuvius Challenge will continue in 2024 with huge sums of money up for grabs for anyone who can help speed up the process of detecting text within the scrolls. The next goal is to uncover 90% of the text across all four scrolls which have been scanned.

The growth is becoming exponential, and the infinite tantalizing possibilities may soon become finite, but, most importantly, known.

Why do the ancient texts really matter?

It’s great fun to learn about history for curiosity’s sake. But the value of Ancient Greece (and Ancient Rome) is not mere history, but serves as a guiding cultural repository and resource in interplay with our own world. What actually happened in ancient Greece doesn’t matter as much as how we project our own ideals, desires, and anxieties upon them, whence those ideas take on a sheen of their own and are reflected back to us: transformed, legitimized, and co-opted.

When the Herculaneum scrolls were being ‘unrolled’ with great difficulty in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was a time when ancient Greece was idealized as a paragon of reason, philosophy, athletics, art, and (in some radical circles) democracy. The reality of ancient Greece was not so perfect, but in perceiving it so, the powerful European empires could emulate and try to match this idealized myth.

In so doing, they crafted many of the institutions that organize our lives today. The columns and pediments of the ancient Greek temple is the global architectural language for authority – from the US Capitol Building to modest town halls all over the world. The ‘democratic’ ancients gave American, French, and even the modern Greeks the courage to break free of tyrannical control. And on the eve of the 2024 Olympic torch lighting ceremony in Olympia, we can reflect on the connection between a healthy body and a healthy body-politic of global cooperation, in force since the 1896 revival of the Olympic Games.

The 21st century world has different tastes, and a different view of ancient Greece. Yet who knows what creations the newly recovered texts will spark? Whatever the case, finding out may be a few million dollars well spent.

Further Reading

There are recommended books, talks, and documentaries at the Vesuvius Challenge’s website: https://scrollprize.org/faq

The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum: Archaeology, Reception, and Digital Reconstruction. 2010. Edited by Mantha Zarmakoupi. Walter de Gruyter.

Herculaneum: Past and Future. 2011. Andrew Wallace-Hadrill. Frances Lincoln.

Epicureanism: A Very Short Introduction. 2015. Catherine Wilson. Oxford University Press.

A catalogue of the papyri: https://www.chartes.it/

https://scrollprize.org/grandprize

Extract of a Letter from Signor Camillo Paderni, to Dr. Mead, concerning the Antiquities Dug up from the Antient Herculaneum”, 1752. urn:doi:10.1098/rstl.1753.0010

“How Much Text do the Closed Rolls Contain? A Quantification Attempt”, Die Papyri Herkulaneums im Digitalen Zeitalter. 2021. Kilian Fleischer. De Gruyter.

Both Philodemus and Piso were long dead by the time of Vesuvius’ eruption, yet the recovered scrolls appear to be from their lifetimes. Whether later owners of the villa added to or detracted from the hypothetical ‘main library’ remains to be seen.

Wow this is exciting! New technology reading unopened and burned scrolls is near miraculous though I don't envy the amount of work that needs to be done. If written works that are known, from translation, can be found it would be interesting to read how accurately they were transcribed and translated over the centuries. Louie T.

I've got another Herculaneum question for you. It makes perfect sense that the most papyri would be in the home of a rich bibliophile who patronized a supported a philosophical writer on site.

But why haven't we found at least a few other carbonized paypri spread through Herculaneum? Is there something special about the villa, or were scrolls really that rare?