The tale of a 3,000-year old text

What one ancient manuscript's footnotes can teach us about history, and ourselves

The year is 1423.

The setting: Constantinople’s harbour.

The squawking of seagulls never ceases as the setting sun glazes across crates being hoisted onto a three-sail merchant vessel. An Italian historian and diplomat, Giovanni Aurispa, watches carefully until all the crates are dutifully onboard.

Aurispa walks across the gangplank, takes his first step onboard the ship and breathes a sigh of relief. The crew signal the ship’s departure and Aurispa turns back to the walled city and, over the ascending rooftops, just barely glimpses the shimmering dome of Agia Sophia, the holy cathedral of Christendom. He imagines the palace over the hill and his heart races again. Earlier in the day he had received a letter with a most unusual seal representing “Ioannis VIII the Palaiologos in Christ, Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans”. Or, as the Italians knew him: The Emperor of the Greeks.

He read the letter in shock, and hastily made arrangements for departure. He pulls the letter out and recalls its contents. A furious letter, written with a pomp of imperial Greek almost illegible to Aurispa. But the furious tone comes through and the message is clear, the Emperor is denouncing Aurispa for his purchase of ‘all the sacred texts in the city’. Looking to the city now as it begins to shrink from view, Aurispa sees Ottoman encampments encroaching all around the capital of the once great empire. An empire which now is reduced to little more than one fortified, petrified city.

Aurispa gazes again at the crates, holding the treasure of ancient Greek manuscripts. Secure, safe, rescued. He lets the Emperor’s letter drift from his hands and float down to slowly submerge under the water. He turns westward.

The destination: Venice.1

…So goes the story, recounted at a higher-level in my previous post on when Western Europe became the centre of Greek scholarship after Italian scholars and Greek refugees worked to empty Constantinople and its declining Byzantine palaces, libraries, monasteries, and schools of whatever classical Greek (and Christian) manuscript they could get their hands on. 30 years prior to Aurispa’s arrival in Venice with 238 Greek manuscripts, there was no Greek-language school in western Europe and few could read any Greek. 30 years after, and Constantinople had fallen to the Ottoman Turks and the torch of classical Greek learning was passed to the Italians. From there, the Renaissance flowered and eventually new technologies and mindsets that would lead to science and the modern world we know today.

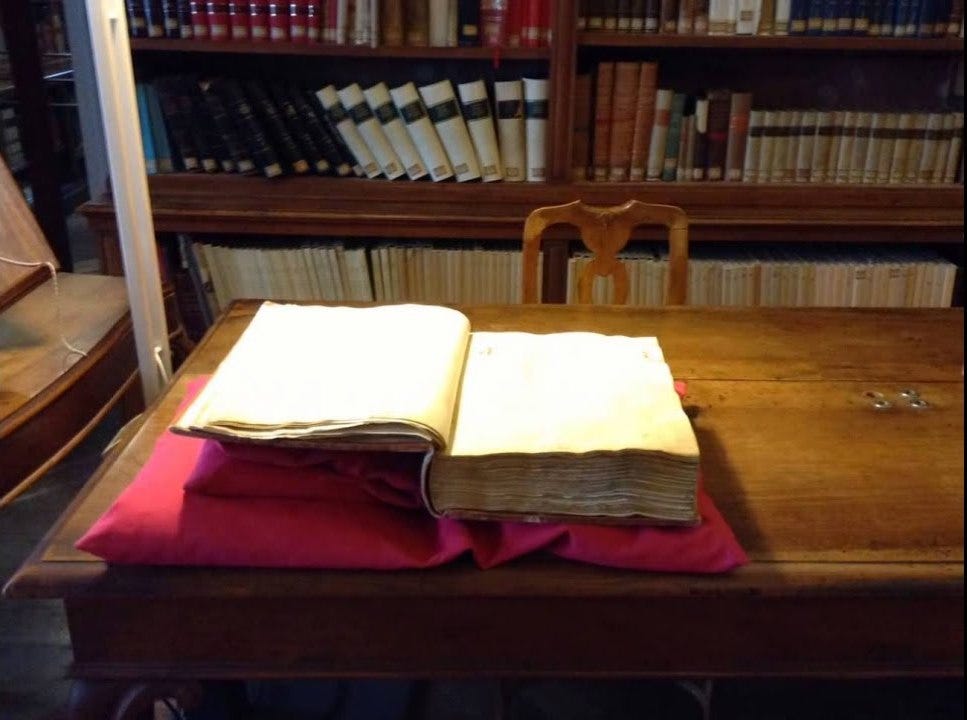

One of the most beautiful books in Aurispa’s collection, now known as the Venetus A, had an unknown provenance (which is still unclear), an unknown scribe (likely forever unknown), and an age perhaps from beyond time itself (discovered more recently to be from around the middle of the 10th century). It contains the oldest still-existing full copy of one of the oldest pieces of literature in the world: The Iliad by Homer. It contains 654 pages, the full 16,000 lines or so of Iliadic text, plus thousands of lines of commentary from ancient scholars (more on that below), several pages of illuminated artwork, and it’s all bound cover to cover and written on the highest quality vellum in a package 40cm x 30cm x 10cm.

The Venetus A is a deluxe edition of the legendary story by Homer which – composed thousands of years before today (and before literacy itself) – is one of the most influential texts in the world. From Socrates the Philosopher to Alexander the Conqueror to Cleopatra the Pharaoh to Marcus the Stoic to Augustine the Saint to Sinbad the Sailor to Dante the Poet to Shakespeare the Playwright to Raphael the Painter to Jefferson the President to Freud the Psychoanalyst to Atwood the Novelist to Colombian villagers who refused in the 1990s to return The Iliad after it was loaned to them from an itinerant library in their village. They said they couldn’t bear to part with it because it reflected their own world: “It told of a war-torn country in which insane gods mix with men and women who never know exactly what the fighting is about, or when they will be happy, or why they will be killed”.

All have been impacted by Homer. For some, Homer is the fountainhead of culture itself, for others, it is the joy and breadth of its impartiality and honesty that make room for limitless interpretations.

“The more I read the Greeks, the more I realize that nothing like them has ever appeared in the world since... How can an educated person stay away from the Greeks? I have always been far more interested in them than science.” – Albert Einstein

Several decades after Aurispa brought his books to Venice, many of them were sold to a Greek scholar and Cardinal-who-nearly-became-Pope, Basilios Bessarion. Bessarion, not unlike Aurispa, sought for Greeks texts to have refuge in the Italian peninsula now that Constantinople was in the hands of an Ottoman Sultan. He recognized the incredible value of the manuscript, and sought to replace the missing pages himself, creating a fully complete text of The Iliad. Shortly before the death of Bessarion in 1472, he negotiated an Act of Donation with the Republic of Venice to create a public library which would preserve his collection of hundreds of Greek books, enlighten Europe with works as yet unknown, and keep the books “in some safe place, where they would be accessible to all readers” until Greece was once again free.

Bessarion chose the protectors of Greek knowledge well since the Venetians, who treasured the books themselves, preserved the books with care. No one knew when the Greeks would reclaim their independence, and the Greeks wouldn’t begin to assert independence until the 1800s (and never did reclaim Constantinople). Indeed, Bessarion’s texts formed the very basis of St. Mark’s Library (Biblioteca Marciana) which still sits at the heart of Venice, which for centuries was one of the most wealthy and important cities in the world. Until the physical building was built in 1565 to hold these texts, the manuscripts were so valuable they were kept right inside the Doge’s Palace. Over five centuries later, the manuscript is still held behind lock and key at the Marciana Library, with access heavily restricted.

Yet after Bessarion’s close attention to the Venetus A, the manuscript remained almost a secret, hidden away without reference during the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. With the promise of the printing press to create exact copies of a literary work, the millennia old tradition of deeply cared for hand-copied, illuminated manuscripts fell away. The first printed edition of The Iliad was made in 1488 (without reference to the Venetus A, mind you), and many manuscripts sat dusty and neglected on their shelves.

Hidden, that is, until the grumbles of the political climate in France threatened to burst into the all-out chaos known as the French Revolution. The French humanist Jean-Baptiste-Gaspard d’Ansse de Villoison, despite the distractions of French political life, scoured libraries in the 1780s looking for outstanding manuscripts of The Iliad. In fact, a better way of putting it may be that precisely because of the political upheavals that surround a would-be revolution, The Iliad and other Greek texts were sought out. These were the texts that sparked the Renaissance, the Reformation, and indirectly even Science itself, why wouldn’t they play a part in igniting new political and economic revolutions? After Napoleon Bonaparte defeated the Republic of Venice in 1797, the Venetus A along with many other books from the Marciana Library ended up in Paris, although they were all restored to Venice again by 1816.

The Iliad, however, isn’t exactly a political manifesto. It’s a snapshot of a 10-year long war between the Trojans and Greeks and the role of the gods. Themes of glory, war, and anger are central, but so too are grief, friendship, dislocation, identity, morality, and songs of lamentation. Since its composition, it has been used as a guiding light, as a place of criticism, as a literary and linguistic guide, and a cultural wellspring. The Iliad isn’t a ‘story’ in the way Harry Potter may be today, but as something either literally or implicitly sacred which plays a role across the ages in religion, performance, politics, history, mythology, and literature.

Plato, in creating a utopian vision in the 4th century BC, stated that works of ‘high art’ like Homer’s could never have a place in his utopian republic because it doesn’t truly create anything (a vast simplification, but let’s not delve into philosophy here). The irony of Plato’s position is that he can’t help but use Homer in his own work – 331 times in his Dialogues alone. In that completely different world than our own, The Iliad could be defined as simply information. Perhaps having deleterious or noxious influence, sure, but information nonetheless. Fundamentally true information.

I digress. In 1788, one year before the full-on outbreak of the French Revolution, Villoison published a print edition of the marvelous book that was catalogued in the Marciana library as number 454 (and later received the call number of 822), otherwise known as the Venetus A (the full designation of the manuscript is Marcianus Graecus Z. 454 (=822)). This publication shook the world of history to its core. What is so special about the Venetus A isn’t necessarily its ancient provenance and complete text of The Iliad. Otherwise, a printed edition of the Venetus A manuscript would be interesting in presenting perhaps some new or different lines from The Iliad, but not much more. What the Venetus A and Villoison’s print version of the book highlight are the scholia from the Venetus A.

Scholia are the ancient origins of modern day footnotes and hypertext. They are comments from ancient scholars about The Iliad, such as Librarians from Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. So far in this article I’ve mentioned about 350 years of history of one manuscript of The Iliad (from 1423AD to 1788AD), but the story of The Iliad’s transmission goes at least 2000 years before Aurispa absconded from Constantinople with crates of texts. One can imagine the difficulty in transmitting the thousands of words under the toils of the thousands of years.

The scholia preserve thousands of comments from ancient scholars who were trying to preserve the meaning and form of The Iliad as they copied it again and again, and ultimately who were trying to uncover the true, original text of The Iliad. The scholia discuss letter, word and accentuation choice as well as discussions about the meaning of whole passages, definitions of words, where lines should or shouldn’t be placed, questions of authenticity, and justifications for their editorial decisions. The way the book is bound, the font used, the placement of the elements on the page, analyses of the age of the ink, and the type of handwriting help scholars today learn about the process of the Iliadic transmission, and from there, about history itself.

Through this type of analysis, we learn that the Venetus A was written by a scribe whose identity we will never know, took about ten years to write the manuscript, and that this work took place some time in the middle of the 10th century AD. There were additions to the manuscript later, such as illustrations on the Epic Cycle of stories which surround the events of The Iliad, but very few additions overall.

Scholia can preserve fragments of the works of otherwise lost texts. Aristarchus of Samothrace, a librarian of Alexandria in the 2nd century BC, worked with an unknown number of papyrus scrolls of Homer’s works to try and devise the ‘true’ text of The Iliad. The scholia and other evidence from the Venetus A can help us determine how The Iliad was written, edited, and stored on papyrus scrolls at the ancient library.

The scholia can take us back further still, to the 4th century BC when Plato and Aristotle used Homer’s vocabulary to discuss Homeric poetry. The 3rd century AD philosopher Porphyry wrote a now-lost text about the “parlor games” of his day, when intelligent aristocrats debated ethical, legal, and historical topics using the words of Homer and those who spoke of Homer, such as Plato and Aristotle. Scholia is one way we have the texts of those great philosophers. If this is becoming confusing, that’s okay. The point is that the Venetus A contains several layers of quotations going back through the centuries not just to The Iliad, but other philosophers, poets, scribes, and scholars along the way. My next article will go in more depth here.

The publication of the Venetus A by Villoison led to modern debates, too. The amount of scholia had never been seen before, and they helped fuel the age-old question about who Homer was, and how we can create the perfect, original text of The Iliad. Villoison believed that his publication of the Venetus A solved the problem. He argued that Homer existed and that the true, original text of the genius of Homer can be recompiled with the Iliadic text and scholia of the Venetus A. However, a German scholar, Friedrich August Wolf, argued that the evidence provided by the Venetus A actually points to an oral, not a written tradition that has become corrupted over time as texts continue to be copied with subtle errors and scholars try and fix those errors. Therefore, the “true” original can never be recovered or even reconstructed.

In the 1930s, American scholars Milman Perry and Albert Lord showed decisively that the works of Homer were composed orally during traditional performances, likely before the 7th century BC (which is the time they were first written down) and as far back as the 12th century BC. A student of Albert Lord, Gregory Nagy, who is now the director of the Washington D.C.-based Harvard-affiliated institute Center for Hellenic Studies, continues this lineage and takes it still further. Not only were Homer’s works the product of an oral tradition, Nagy says, but there is no single creator of the works attributed to Homer. As such there was never a single, true, oldest, or purest form of the poems. It is in the multiplicity, the “multitext” as he and his team call it, that the ‘true’ form can exist.

Some say, ‘There never was such a person as Homer.’—‘No such person as Homer! On the contrary,’ say others, ‘there were scores.’ – Thomas de Quincey, “Homer and the Homeridae” (1841)

Along with many other colleagues, Nagy has co-created The Homer Multitext Project. For as much as Villoison’s publication changed our view of ancient Greece, his printed edition of the Venetus A left out a lot of its scholia and other details from the manuscript, and muddled some of the information by including text and scholia from other manuscripts. The spatial composition of information on each page of the Venetus A is also integral to a full understanding of the manuscript, which the printed book upends by placing the scholia at the back of the book. The Homer Multitext Project aims to present the Venetus A, and other Homeric manuscripts, in their full detail through photographic images, fully searchable and indexed using digital tools.

In my next article, using the tools available to me from the Homer Multitext Project and other resources, I will dive into one page of the Iliadic text in the Venetus A to explore and describe how the scholia works and how the different elements of the page interface with each other. I will outline the lineage tree of the scholars, poets, and philosophers who referenced and wrote commentaries on The Iliad, and define at least part of what they said.

In so doing, I hope to continue to uncover and understand the complicated process by which we know (or can deduce) what the ancient Greeks said all those thousands of years ago. The Venetus A is not a typical manuscript, but many of the elements present in it can also be found in other manuscripts which are the source of much knowledge about ancient Greece.

I also hope through my articles to illuminate how we are still all a part of history of the transmission of The Iliad. Through the years, the Venetus A has followed the waves of history and weaved its way through successive centres of each era’s highest economic and political power as it transferred from Constantinople, to Venice, to Paris, and – through its digital incarnation – to Washington, D.C. As the donor Bessarion wished over 500 years ago, the book is now not only kept safe but is accessible to anyone who cares to look.

That’s a wonderful thing, because the display and complexity of information in the Venetus A proves that the scribe who wrote it out was a master in information technology. Like other works on Homer and ancient Greece, understanding the layers of information in the Venetus A is not just important to grasp the words written on its pages but for grasping just why there is a close link between a society’s level of prosperity and its level of interest in the Classics and its own history. Just as the capitals of power have leveraged Homer — as the life history of the Venetus A shows us— with the new tools freely available; so can you.

For sources on this research, please check out my post below. I continually update it with my sources as I work on these articles. If you are looking for a specific reference, please comment and I will do my best to help you.

This is one fictionalized telling of how hundreds of manuscripts reached Venice through Giovanni Aurispa. The characters, Emperor’s denouncement, and general theme is recorded but the exact timing and occurrence of these events aren’t known to history.