Where are the world's Greek manuscripts?

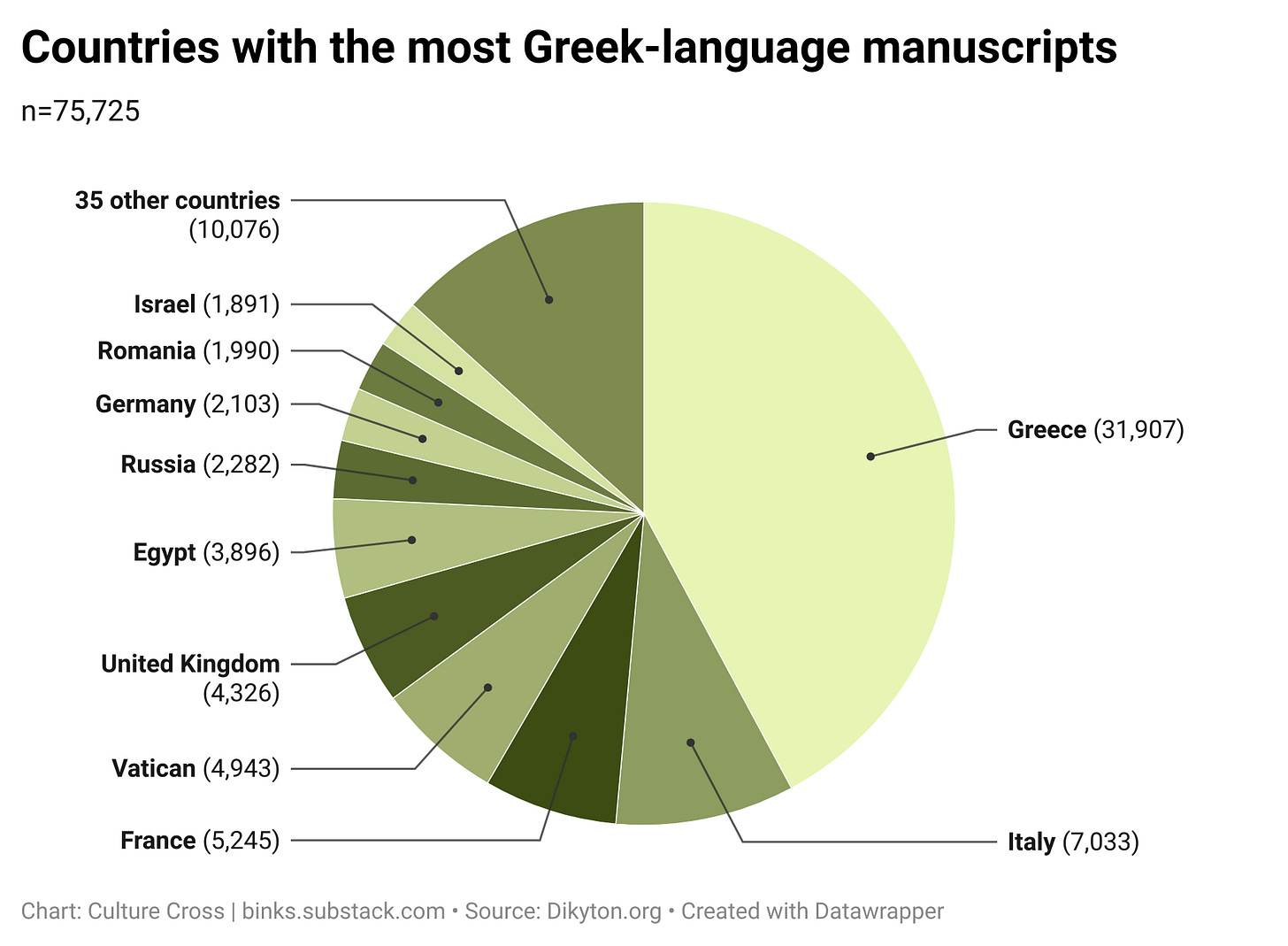

There are 75,725 known Greek-language manuscripts in the world.

There are 75,725 known Greek-language manuscripts in the world (as of January 2019). How can I know this? Almost every Greek manuscript receives a unique identifier called a Dikyton number1. Dikyton.org makes available a list of all Dikyton numbers and basic information such as where the manuscript is located.

Hover over the country to see the quantity of manuscripts.

The manuscripts are currently held in 45 different countries around the world. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the highest number of them are in Greece (31,907, which represents 42% of the total). However, many – perhaps even the majority – of these old manuscripts were not produced within the boundaries of the modern nation of Greece, but in other regions where the Greek language was a key language for politics, scholarship, and religion.

The city of Constantinople – which is now Istanbul in the nation of Turkey – used to be the capital of the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman) Empire, the polity within which a huge number of these manuscripts were created. During the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries, many of these manuscripts were rescued and brought to Western Europe, especially Italy. This is why Turkey now has 1,468 Greek-language manuscripts (representing just 2% of the total) while Italy and Vatican City combined have 11,976 (16%).

The manuscripts are held in 1,241 repositories. Many of these are state and university libraries, but there are also a huge number of manuscripts in Christian monasteries and Patriarchal Christian libraries, too.

When were these manuscripts made?

Manuscripts that are assigned a Dikyton number can contain text on any subject as long as they’re in the Greek language. Unfortunately, alongside the Dikyton number is only a small amount of metadata, such as the location of the manuscript. There are plans to include additional metadata, such as the manuscripts’ authors, associated texts, and owners of the manuscripts, but that information isn’t included yet.

The largest database that identifies Greek manuscripts is called Pinakes. Pinakes records manuscripts’ Dikyton number along with a host of useful metadata. I have recently been taking courses on digital humanities which allow me to extract and analyse vast sums of humanities information. Unfortunately, I’m not yet able to extract all the associated Dikyton numbers with the other metadata that Pinakes compiles for each manuscript.

However, the librarian for Classics, Hellenic Studies, and Linguistics at Princeton University Library, David Jenkins, has compiled a database which records all the digitized and freely accessible Greek-language manuscripts in the world. As of November 2023 that number stands at 15,544. Although this represents just 20% of the total number of Greek-language manuscripts, Jenkins believes this selection of digitized manuscripts is a fairly representative sample of all existing Greek-language manuscripts.2

Thankfully, Jenkins has recorded metadata for most manuscripts in his database. With this metadata some fascinating findings can be made. For instance, when were Greek manuscripts made?

Creating a manuscript by hand, often over hundreds of pages, was a long and expensive process. About 85% of datable manuscripts are estimated to have been created in a single century. For some manuscripts, it may not be clear exactly in which century it was created, or there may be additional pages that were added to the manuscript at a different time. The 15% of manuscripts whose creation is attributed to multiple centuries have the same distribution across the chronology of centuries as the datable single-century manuscripts.3

Most of the manuscripts were created from the middle Byzantine period (9th century) until the invention of the printing press (in the 15th century). There were many earlier manuscripts but most have been lost to time.

Anytime a new technology like the printing press is introduced, it doesn’t immediately conclude the use of earlier technology, especially in the case of beautiful hand-written and illustrated illuminated manuscripts. However, I’m not sure why so many manuscripts continued to be produced well into the 18th century. One thing to be certain is that the later creation of a manuscript does not necessarily mean it contains worse or even less ancient information in its text.

How many manuscripts have Christian vs. Profane subject matter?

By counting and analysing each manuscript entry based on its different type of metadata, I’m able to present more and more refined data on different elements of the collection of Greek manuscripts. For example, how popular were certain texts or authors over time? This kind of information can be apparent in the number of manuscripts which contain those texts or authors.

We saw earlier how the repositories with the highest number of Greek-language manuscripts were a mixture of state, academic, and religious (i.e. Christian) libraries. Greek is an important language for the history and theology of Christianity and as a liturgical language for the administering of Christian rites. One would expect a large number of manuscripts to thus contain text important for Christian study, worship, and practice.

Greek is also the language within which a huge array of non-Christian or secular — what I will call ‘profane’ — topics were expressed: grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, poetry, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, science, mythology, etc. When I say profane, I don’t use it in a negative or derogatory sense, nor as something anti-religious. Profane here means that something is not sacred from a Christian point of view. It may be highly valued and important, but it’s not specifically a text written for Christian worship (like a hymn book or Psalter) nor a text to organize the administration of a church or indeed The Church as a whole (like Church Councils or a Book of Hours).

So, how many (digitized) Greek-language manuscripts are mainly concerned with strictly Christian topics and by extension, how many are not?

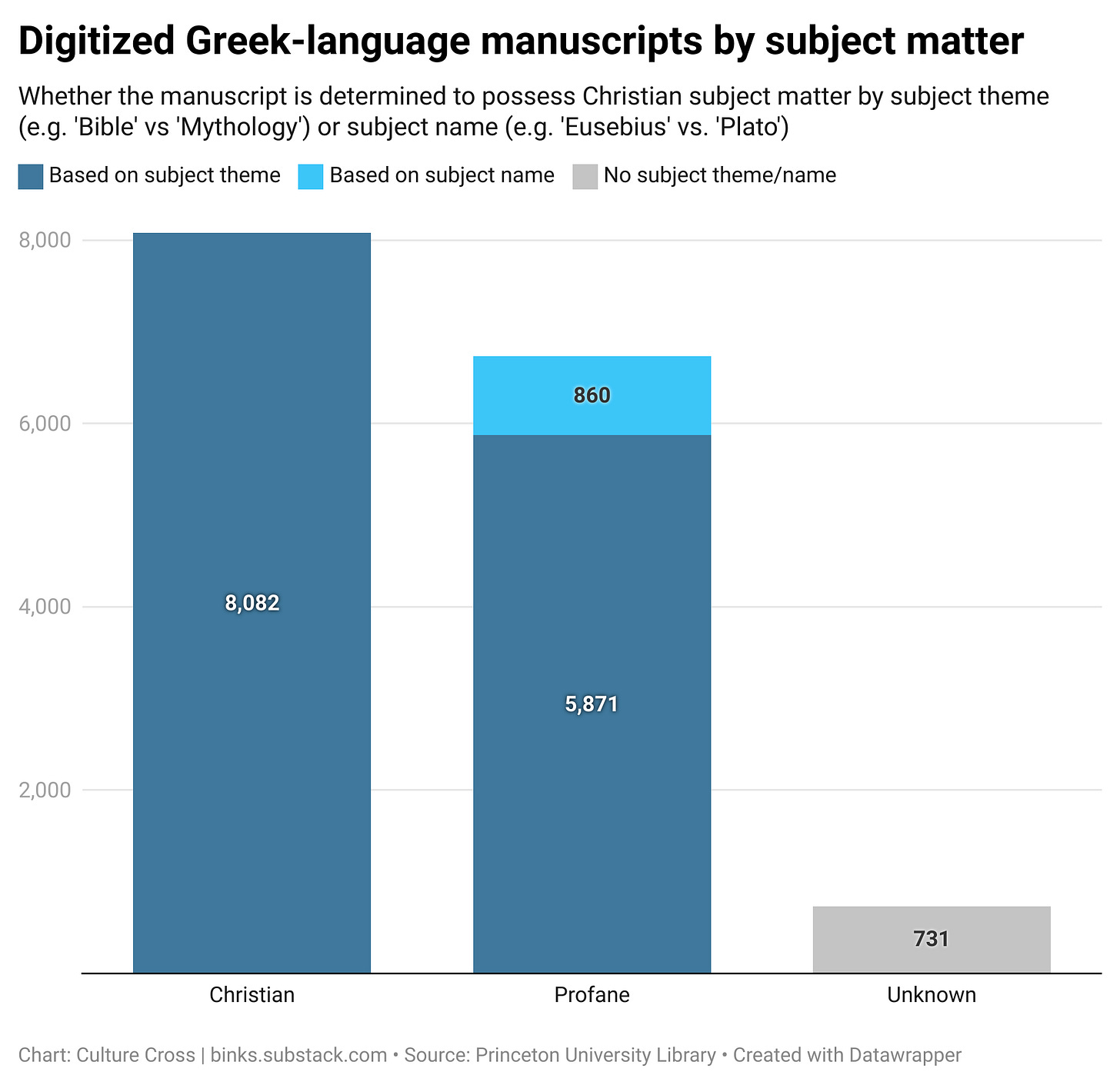

Jenkins has created 84 “subject themes” which he assigns to the manuscripts in the database, such as ‘Philosophy’, ‘Bible’, ‘Grammar’, or ‘Liturgy’. Since many manuscripts have a variety of text within them, a single manuscript can have up to 7 different subject themes assigned to them. Out of the 84 subject themes, I concluded that 29 of them are explicitly Christian subject themes4. It’s an imperfect method, but if I select all manuscripts with at least one of those 29 Christian subject themes then I can begin to get a measure of how many manuscripts primarily contain texts for Christian study or practice.

However, 1,591 manuscripts have no subject theme. Before stating these manuscripts do or do not contain Christian material, I looked at another category of subject matter, the “subject name”. The subject name is the original author of text contained in the manuscript, so the manuscript could contain a copy of text from a pre-Christian Greek author (“subject name”) like Homer or Strabo or it could be the text of a medieval Greek writer (“subject name”) like Michael Psellos or John Tzetzes.

About half of the manuscripts without a subject theme also do not have a subject name (n=731); I did not include those manuscripts in my subsequent calculations.

Those without a subject theme but with a subject name (n=860) almost universally have a subject name of a pre-Christian author, and therefore these are included as Profane manuscripts.

With these parameters, I ended up with 8,082 ‘Christian’ manuscripts (i.e. manuscripts that contain at least one of 29 Christian subject themes) and 6,731 ‘Profane’ manuscripts (i.e. manuscripts that do not contain any of the 29 Christian subject themes but, in absence of any subject theme, do have a pre-Christian subject name).

Again, this is an imperfect method. ‘Christian’ manuscripts could contain only a small part of one of the 29 Christian subject themes but otherwise be filled with texts of, say, the Socratic Method. Or the text may not be noted as a Psalter or Bible or as containing ‘theology’ but still contains Christian religious references in the form of a poem. Likewise, just because a manuscript doesn’t contain any of the 29 Christian subject themes doesn’t mean it’s filled with classical Greek Athenian texts. The subject theme of “Grammar” may just contain lexicological information. There is also the subject theme “Islam” which goes into the category of ‘Profane’ (because from a strictly Christian point of view it is not a sacred text).

I would need to look in detail at each manuscript to more comprehensively state which are ‘Christian’ (or any subject matter or not), but this gives us a good start.

Where are the ‘Christian’ and where are the ‘Profane’ manuscripts?

Using the categorization outlined above, I can then determine where in the world are Greek-language manuscripts with at least one ‘Christian’ subject theme, and where are the manuscripts without a ‘Christian’ subject theme (i.e. Profane).

Remember that this categorization is based only on the 15,544 manuscripts that are digitized and listed on Princeton University Library’s database. I doubt whether this distribution would remain true if I were able to analyze all 75,725 Greek-language manuscripts. For example, less than 5% of all Greek-language manuscripts in Greece have been digitized, despite Greece being home to 42% of all Greek-language manuscripts. This single statistic shows that nearly 40% of manuscripts are not accounted for here. Many of Greece’s manuscripts are held in monasteries, which may suggest a greater proportion of Christian manuscripts (however, Christian monasteries surely do not only possess Christian texts).

Perhaps what is more useful to note is the ratio of how many (digitized) manuscripts in each country are ‘Christian’ (per my analysis) and how many are ‘Profane’. The same limitation exists: some manuscripts may have been chosen to be digitized over others. Nonetheless this factor in itself says something significant about the direction and valuation of each country or institution regarding what manuscripts are valuable to possess and/or digitize.

In the chart above, I selected countries whose collection of Christian manuscripts heavily outweighs their collection of Profane manuscripts, or vice versa. I broke this rule only for Vatican City because I found it interesting that according to these calculations the number of Profane manuscripts outweigh Christian ones.

Although I can not make any definitive statements or even hypotheses about why these collections favour one over the other. This is particularly difficult in cases where there are a relatively small number of manuscripts in general, as the proportion of manuscripts could be due to a single collector, scholar, or institution’s interests at just one period of time. However, I can make a few basic estimations.

Neither Italy nor Vatican City existed as nations in their modern sense during the time when many or even most of their Greek manuscripts were collected from the faltering Byzantine Empire. Both of these countries’ collections favour Profane manuscripts, which may be a result of the time period in which they were collected. Italy was the centre of the Renaissance, which was a time of renewed interest in the pre-Christian past of ancient Greece and Italy. It was also a time when more and more Profane texts were produced in general in order to support growing secular scholarship.

Most of Greece’s and Egypt’s manuscripts are in Christian monasteries and likely have been utilized to serve the day-to-day functioning of these spaces.

The Greek language is important for Christianity writ large, but in particular as a language for the Greek Orthodox Church. Perhaps this is why countries with larger Orthodox populations (like Romania and Russia) have a greater proportion of Christian manuscripts, while countries with smaller Orthodox populations (like Austria, Netherlands, Poland, and Sweden) have a smaller proportion of Christian manuscripts.

Israel’s manuscripts are primarily in Jerusalem, which is a holy city for Christianity. Jerusalem is also home to one of four Orthodox Patriarchates and a Patriarchal Library, which is perhaps why there is a greater proportion of Christian manuscripts.

Other than Ireland (which has a small number of manuscripts), the USA has the greatest proportion of Christian to Profane manuscripts (about 5:1). I won’t hazard a guess as to why this is the case.

Limitations: What is(n’t) a “Greek-Language Manuscript”?

I have already hinted at a few limitations to the datasets I have used in this essay, but it bears expanding.

Greek-language manuscripts are the source of the vast majority of our knowledge about ancient Greece, especially non-Christian elements of ancient Greece. I include the hyphen with ‘language’ because there are many manuscripts which contain ‘Greek’ material but in translation in other languages, such as Latin, Syriac, and Arabic. Those other languages are not included in these databases.

“Manuscript” here means a book inscribed by hand. Therefore this list doesn’t include printed books in its equation, however, almost any ancient Greek text which has been printed since the invention of the movable printing press (in 1440AD) has its own original source in the manuscripts which are included in the Dikyton and Princeton University Library databases.

The datasets analysed here also do not include papyrus rolls or fragments, which are where the world’s oldest extant Greek literature is preserved. There is a database that tracks extant papyrus (papyri.info), which I would love to analyse in the future. Even more ancient are Greek epigraphy and inscriptions on stone, which the databases I used in this research do not contain.

Despite these limitations in the datasets, most of the world’s Greek literature are still contained within the tens of thousands of manuscripts analysed here. My foray into understanding the quantities and locations of these manuscripts by Christian and Profane subject matters is just a first step into an area I intend to explore further.

Within these datasets I can fine-tune my searches to shed light on the volume and location of individual authors (e.g. Plutarch), groups of texts/authors (e.g. Golden Age tragedians), or a variety of other subjects from astronomy to zoology. If I’m able to unlock the whole of the Dikyton/Pinakes and Papyri databases I can expand this search even deeper to include specific texts (e.g. Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War), movements of manuscripts as they are procured by different owners, and centuries further back into time that will provide an even fuller picture of the story of Greek texts’ journeys towards the paperbacks of today.

If all this sounds interesting, please do subscribe to receive my future essays. Please leave a comment with any questions you may have, or if there is a topic I may be able to elucidate with this type of quantitative data.

Dikyton doesn’t actually track ‘manuscripts’, but ‘shelf marks’. A shelf-mark is a code which identifies where in a specific repository the particular item is kept. A shelf-mark could be an entire manuscript or just a page fragment. A single manuscript can even be represented by multiple shelf-marks if the manuscript was broken up and has ended up in multiple repositories (such as the Codex Sinaiticus, an early copy of the Bible which lives on four separate shelves around the world). For simplicity’s sake, I nevertheless use the word ‘manuscript’ even if technically I mean a ‘shelf-mark’. See the “Limitations” section of the essay for more detail on what manuscripts are and aren’t included in these datasets.

(Dec 3, 2020) Byzantium & Friends: #38 “Manuscripts, databases, and the joys of Byzantine literature with Dave Jenkins”, hosted by Anthony Kaldellis. https://byzantiumandfriends.podbean.com/e/38-manuscripts-databases-and-the-joys-of-byzantine-literature-with-dave-jenkins/

As seen in Jenkins’ own analysis of chronological distribution of manuscripts which is hosted on the Princeton University Library Digitized Greek Manuscripts webpage (accessible on November 26, 2023 here: https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1WTYKKPhlgJjVn0vfPB6ww-w1QY9mIYHJxbppeSJ4Hys/edit#slide=id.gd09d1ae4dd_0_0)

The 29 Christian subject themes I selected are: Anthologion, Apocrypha, Barlaam and Joasaph, Bible, Canon law, Christus patiens, Church councils, Constantinople, Contra ludaeos, Euchologion, Gospel lectionary, Heirmologion, Hieratikon micron, Horologion, Iconoclasm, Liturgy, Menaion, Monasteries, Old Testament, Pentekostarion, Procatechesis, Psalter, Saints lives, Sticherarion, Synaxarion, Synodicon vetus, Theology, Theotokarion, Triodion, Typikon

Thanks James! In addition to a fascinating analysis, it helps me understand what digital humanities is! Where are you taking your courses?

Thank you for another educational and interesting article. Looking forward to your next post.